Key takeaway: Good urban planning and climate-conscious infrastructure in new cities can not only improve the built absorptive capacity of the city, but it can also support economic productivity and foster social capital.

— — — —

Climate change will inevitably impact every city on Earth. From bustling coastal hubs to teeming inland metropolises, urban areas of every shape and size must be prepared to withstand extreme weather events and adjust to climatic changes.

The resilience of these cities is critically affected by the quality of their built environment. While robust infrastructure is crucial for weathering climate hazards, the very layout of the city fundamentally affects its capacity to absorb and process shocks. However, many cities today – especially in the Global South – suffer from infrastructure deficits and unsustainable urban sprawl.

Charter cities offer new opportunities to implement good urban planning principles and integrate climate-conscious infrastructure into the foundation of the city. By thinking more holistically about how the built environment influences and interacts with environmental, economic, and social processes, charter cities can foster urban resilience from the initial stages of city development.

Urban form and resilience

Urban resilience is closely linked to urban form. A good, dense urban plan can help make a city more economically productive, decrease per capita emissions, facilitate social interactions, increase access to education and amenities, and support an infrastructurally sound built environment for residents.

However, many cities, particularly in the Global South, are rapidly expanding outwards rather than inwards or upwards. This phenomenon is known as ‘pancake’ growth. Pancake-like urban sprawl occurs largely because cities in developing countries across the Global South are experiencing significant population gains, without accompanying productivity and income gains. This undermines demand for expensive floor space in the city center, which inhibits “vertical layering.”

In cities where urban sprawl is “not managed well, cities will become unlivable.” This is particularly true for low-income households living in informal settlements at the urban periphery. As of 2018, over one billion people worldwide were living in slums. By 2050, this number is expected to increase to three billion, with climate migration contributing to growth.

Although they provide a critical economic lifeline for many residents, unplanned slums – which are often characterized by poor service provision, weak infrastructure, sparse economic resources, environmental degradation, and high risk of exposure to extreme weather events – have high levels of climate vulnerability. Furthermore, informal urban sprawl also heightens mobility constraints for workers. This further undermines household resilience by limiting access to economic opportunities in other areas of the city, especially the city center.

Nonetheless, large-scale infrastructure retrofits are costly, cumbersome, and require a high degree of coordination. The billions of dollars that have already been poured into retrofitting and slum upgrading projects do not even begin to chip away at the $4.1-4.5 trillion of infrastructure investment needed annually, nor the $120 billion of additional adaptation costs.

More often than not, “cities become ‘locked-in’ to particular patterns of energy and resource use – constrained by existing infrastructural investments, sunk costs, institutional rigidities and vested interests.” In fact, “urban infrastructure is [so] difficult to modify…[it] often remains in situ for more than 150 years.”¹ This makes the importance of good urban planning all the more imperative: failure to build sustainably now could have resounding effects over the long run.

Sustainable foundations in new cities

While it is extremely important to equip existing cities with the infrastructure necessary to better withstand the effects of climate change, new city construction presents an opportunity to build better cities from the ground up. Urban planning has a clear role to play in managing urban expansion, both at the periphery and beyond.

For example, new satellite charter cities and pre-emptive urban expansion can play an important role in laying sustainable, resilient infrastructural foundations for growing cities. Policies to promote orderly, efficient urban expansion – such as pre-emptively installing arterial roads and public facilities – can help minimize urban sprawl and lay a strong base for future growth.

New cities have the potential to provide large-scale, packaged infrastructure investments that “support the market forces that drive urban economic agglomeration, productive job creation, and income growth,” ultimately improving the quality of life for urban residents. Crucial to this effort is the emphasis on enhancing “livability,” which includes sustainability and resilience.

Green infrastructure and nature-based solutions (NBS) can be particularly effective towards this end. Parks, green corridors, renatured rivers, urban forests, bioswales, and retention areas, green roofs and living walls, urban farming and gardening, and inland wetlands provide a multitude of practical benefits for the cities they serve: excess water absorption during periods of intense rainfall, ‘heat island’ mitigation, air pollution reduction, biodiversity preservation, and environmental protection.

For example, in the city of Freetown, Sierra Leone, the rapid expansion of slums into surrounding forested mountainsides heightened vulnerability to landslides. During heavy rainfall in 2017, a crumbling mountainside collapsed, killing and wounding thousands of residents in the settlement below. In the aftermath of the incident, the government of Freetown turned to large-scale tree planting to help secure the degraded mountainsides and prevent future landslides. In this way, green infrastructure can complement traditional gray infrastructure to increase redundancies in the built environment which enable the city to absorb climate-related shocks more effectively.

Moreover, these spaces can double as both formal and informal community meeting grounds, providing space for the organized and spontaneous interactions that help strengthen social capital. Consequently, the built environment can have a direct impact on social connectivity, the diversity of interaction, and the formulation of social norms in neighborhoods, ultimately reinforcing the cultivation of social resilience.

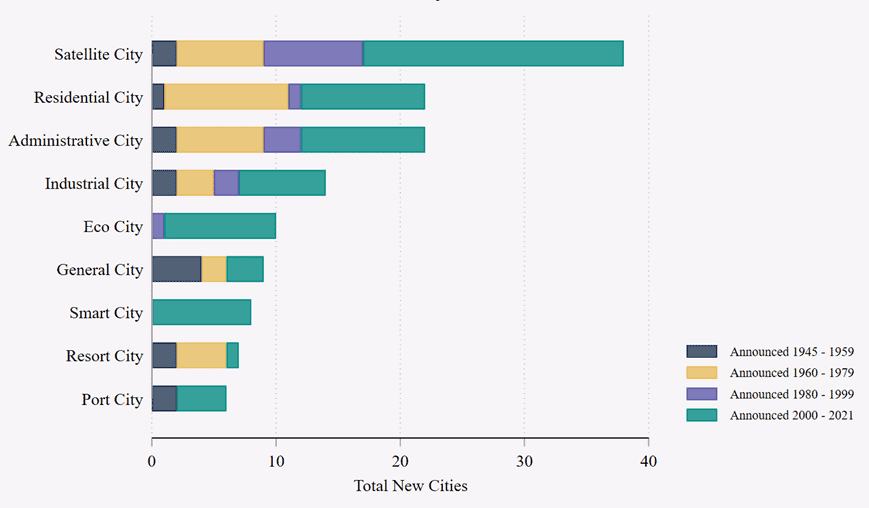

Some new cities are already experimenting with environment-conscious design and infrastructure. Pioneered in Curitiba, Brazil in the 1960s, so-called “eco cities” aim to create a sustainable and livable environment for residents while reducing their impact on the planet. The number of cities explicitly framed as eco cities has increased substantially since 2000, marking the emergence of a new trend in city design and construction.

Source: Author’s calculations using data from the New Cities Database (2023).

However, whether this trend constitutes a substantial shift in the planning approach for new cities ultimately remains to be seen in many cases. Sometimes, developers simply label their projects as ‘environmentally conscious’ to attract investment, without substantive action. The IPCC also notes that the “creation of new eco-friendly cities must be an equitable, inclusive project, otherwise the very goals of the project will likely be undermined by severance of social and cultural ties.”

One example of a particularly successful new, master-planned eco city is Rajarhat New Town, India, a satellite city located outside Kolkata and explicitly designed with the “objective of developing an eco-friendly green dotted city.”

Fumba Town, in Zanzibar, Tanzania, also offers a promising model for how to integrate permaculture into the very built foundation of urban life. Green corridors, ponds, open green spaces, and urban gardens help decrease heat exposure throughout town while providing shaded spaces for community gatherings and markets. The town is also a pioneer in sustainable building, with plans to build the world’s largest cross-laminated timber tower over the next seven years.

Ultimately, the future of urban development hinges on our ability to integrate sustainability, resilience, and inclusivity into the fabric of our cities. From retrofitting existing infrastructure to designing new eco-friendly urban centers, the choices we make today will reverberate for decades.

By prioritizing good urban planning and investing in climate-conscious infrastructure, we can create cities that not only withstand the tests of time and climate but also nurture vibrant communities and ecosystems. The path to resilient cities lies in holistic, forward-thinking approaches that prioritize the well-being of both present and future generations.