Introduction

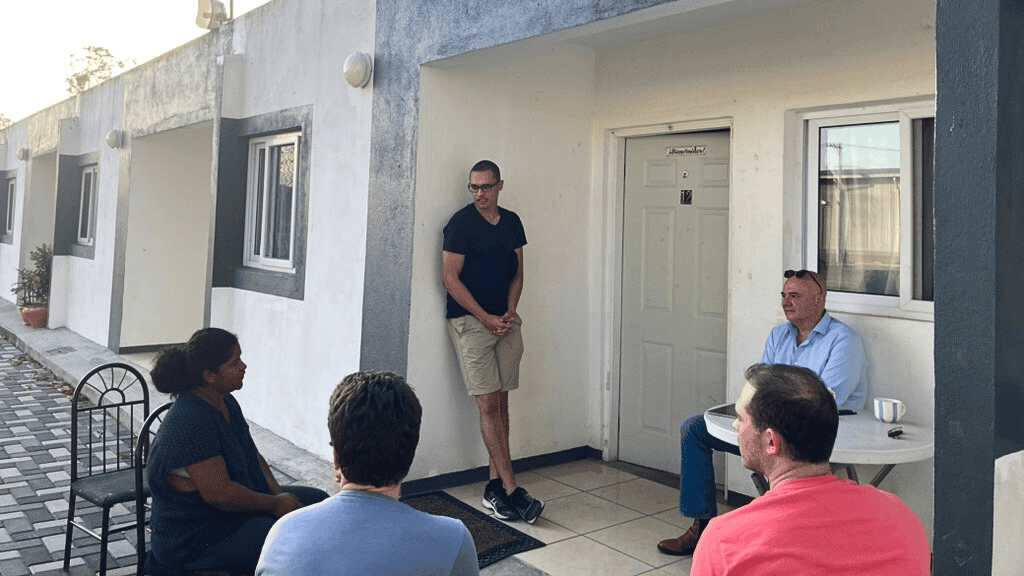

Massimo Mazzone can have a prickly demeanor. The sixty-year-old Italian businessman is usually abrupt and to the point, especially when discussing business. He is unafraid to raise his voice when addressing an employee who isn’t performing up to standard or when discussing his closely held libertarian beliefs, however, his stereotypical Italian temper is paired with an equally stereotypical Italian warmth and ability to select a good wine. He is quick to joke and, like most Italians, is very kind to small children.

Massimo is the Founder and President of Centroamerican Consulting & Capital (3C), a business conglomerate focused on pharmaceutical retail and wholesaling in Latin America, though it has other interests, including distribution, agriculture, real estate, and private education. Owing to Massimo’s role as a pharma executive, Mark Lutter, the founder of the Charter Cities Institute (CCI), has joked that Massimo is one of the largest drug dealers in Latin America. A joke that plays well with English speakers, but falls flat in Spanish as the words for narcotics and prescription drugs are different in that language.

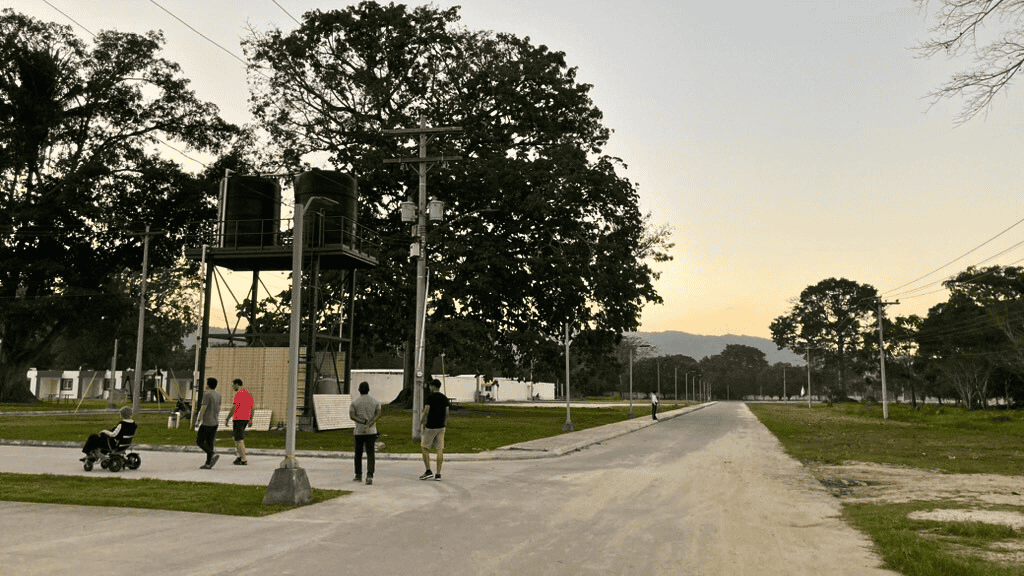

I am sitting with Massimo in an AirBnB in Ciudad Morazán, Honduras while he chain smokes through the course of our interview. Morazán is a Zone for Employment and Economic Development (ZEDE), a type of special economic zone in Honduras that enables radically decentralized governance. Under the ZEDE law, ZEDEs themselves are recognized as local administrative divisions with the same degree of operational and administrative autonomy as municipalities under Honduran law. Massimo, it so happens, is the mastermind behind Morazán, which is likely the most successful charter city project in the world today, based on the number of residents actively living onsite. This is in large part because Massimo is a highly effective business operator. He is laser-focused on customer satisfaction and improved service provision. Massimo believes that good governance should be a service, and he wants to provide the best service possible.

Massimo is a natural libertarian and a natural entrepreneur. As a libertarian, Massimo is very concerned about expanding opportunities for more people to live with more liberty. Outside of Bitcoin, he says, the ZEDEs are the most interesting thing happening in the liberty movement today. This brings in his entrepreneurial side. If he were in charge of Monaco, the micro-state perched on the French Riviera, he would franchise it, he says. He would have one in the Caribbean serving North Americans, and one in the South China Sea serving the Chinese. With a well regarded reputation for effective governance and luxury, “Monaco: Caribbean Sea” or “Monaco: South China Sea” could easily attract top clientele from North American and East Asian countries who would prefer to live in a lower tax environment with better services. While this opportunity isn’t open to him, providing the working class of Honduras with better services than what they would get otherwise is.

Morazán is the culmination of over a decade of political struggle, applied economics, and entrepreneurial sweat. While the road that Massimo has taken to get Morazán to where it is today has been long and tough (with the journey being far from over), Massimo has big plans for Morazán and its model.

How Honduras Got Here

The story of how Honduras got ZEDEs is one that you’ve likely read before if you’re remotely connected to the innovative governance space. However, it’s worth going over broadly to properly understand the environment that led to Ciudad Morazán’s current position. Though feel free to skip this section if you’ve heard it all before.

In 2009, economist and Nobel Laureate Paul Romer pitched the idea of charter cities in a TED Talk. Ultimately, both the governments of Honduras and Madagascar took interest. However, it’s important to note that the Romer Model differs significantly from what charter city advocates today propose. Under Romer’s Model, a host country partners with a “guarantor” or trustee country, with the host turning over land to the trustee to run under the laws and administration of the trustee. This model proved to be unpopular on a number of margins and hasn’t been seriously advanced outside of the initial TED Talk. Though, the general idea of creating a special jurisdiction that operated under a different legal system than that of the host country took off. Ultimately, the idea of charter cities landed in the realm of special economic zones, with a host country creating a special jurisdiction that would be operated either via a public-private partnership (PPP) or as a solely private entity.

Out of the two countries with initial interest in the idea, only Honduras pursued it. In 2011, the government of Porfirio Lobo Sosa passed the Regiones Especiales de Desarollo (RED) law. However, this law quickly ran into trouble with Honduras’ Supreme Court and was struck down. Yet, this didn’t stop advocates for charter cities in Honduras. A second attempt to pass a charter cities law happened in 2013, this one came with some constitutional amendments so that the law would pass the scrutiny of the Supreme Court. This was the ZEDE law.

As mentioned above, under the ZEDE law ZEDEs are given the same degree of operational and administrative autonomy as municipalities have under Honduran law. Additionally, ZEDEs have the ability to adopt their own civil code, which gives them significant latitude to select their own business law. Though, the law makes it clear that ZEDEs are inalienable parts of Honduras that are still subject to Honduran state sovereignty (think defense and foreign affairs) and must abide by and enforce Honduran criminal law.

However, ZEDEs don’t have totally free reign in deciding what their internal policies will be. Functionally, a ZEDE’s internal regulations must be approved by the Committee for Adoption of Best Practices (CAMP) before they can be implemented. CAMP is a group of 21 members appointed by the government to serve in an oversight role for the ZEDEs. The first ZEDE that CAMP approved was the Próspera ZEDE located on the Honduran Caribbean resort island of Roatán. This approval happened at the very end of 2017.

Massimo says that Próspera played a critical role in inspiring Morazán. Though Morazán would ultimately be approved by CAMP at the very end of 2019, Massimo didn’t initially look at starting his own ZEDE, and even initially approached Próspera with his business idea before deciding to strike out on his own. This initial approach to Próspera was because Massimo was motivated by a particular vision of how a city should be run, and he thought that this could be done as a district within Próspera. Ultimately, the pursuit of this vision brought Massimo to start his own ZEDE instead of building a district in Próspera. Massimo’s vision for how a city should be run is that of “Entrepreneurial Communities.”

Entrepreneurial Communities

Massimo is a big fan of the book Entrepreneurial Communities: An Alternative to the State, The Theories of Spencer Heath and Spencer MacCallum. This book, written by “Calvin Duke,” a pseudonymous author, elaborates on the idea of entrepreneurial communities or “entrecomms.”¹ These communities seek to replace the functions of a traditional state on some, or even potentially all, margins. The idea of entrecomms emerges from the Georgist economic school. It is no surprise that a charter city would be so attached to a concept from Georgism.

Georgism is an economic philosophy based on the ideas and writings of Henry George. The main tenant of Georgism is a single tax on the value of land, known as the land value tax. As Bernardo Vicente wrote in a paper for CCI:

Georgism proposes (in its most pure form) a single tax on the unimproved value of land as a replacement for most or all taxes that disincentivize productive land use. Traditional property taxes are assessed on the value of buildings constructed on land, which disincentivizes the construction and maintenance of buildings because each of these will lead to a higher tax bill. Under traditional property taxation, the owner of an empty lot in the middle of a central business district will pay little or no property taxes on that lot despite its clear potential value. Under a land value tax, the owner of that same lot would face a large tax bill or, framed alternatively, a large incentive to use that lot productively. Where property taxation has been replaced with land value taxation, it has been followed by a surge in new construction and a revitalization of the local economy.

The focus on providing an economic incentive to use the land for its most productive purposes goes well with the mission of charter cities to act as engines of economic growth. Georgism also has a long history with libertarianism, and libertarians are some of charter cities’ greatest advocates. So, the relationship between the economic ideology and the solution for economic growth emerged rather naturally. This is especially because charter cities are focused on physical jurisdictions, as opposed to internet oriented movements.

Ultimately, Georgism would go on to inspire other thinkers. One of these thinkers was Spencer Heath. Heath was a man of many talents who not only worked as an attorney, but dabbled in aeronautical engineering, horticulture, and as we will see, economic philosophy. Not wholly happy with all of the tenets of Georgism, Heath went on to provide his own ideological innovations to the economic philosophy.

In his book, Duke has an extensive discussion of Heath and his ideas. Duke says that Heath’s primary ideological difference with Henry George was over the value or necessity of landlords. Whereas strict Georgism views landlords as unfairly extracting unearned rent from tenants, Heath viewed landlords as the necessary medium for providing funding for public services. Rent, and its price, then was a mechanism for conveying the value of land. By allocating land to its most productive use and making its use available to the public via the rental market, a landlord was providing a valuable service to society, rather than unfairly extracting unearned rents.

Duke goes on to discuss how libertarian luminary Murray Rothbard was a big fan of Heath’s. In fact, in his seminal work Man, Economy, and State, Rothbard agrees with Heath’s criticism of Georgism and the necessity of landlords to serve as allocators of land toward the most productive ends. Furthermore, Rothbard, most famous as the father of the extreme libertarian position of anarcho-capitalism, goes on to praise Heath’s work for showing that landlords have the potential to provide all of the services that are traditionally thought of as state services, such as security, public utilities, and the like. Duke says that Heath ultimately comes out arguing that an individual or a for-profit company administering a community without coercion and providing public goods and services with the revenue generated by what amounts to a land value tax paid for via rents is a better arrangement than a contemporary nation-state.

However, Rothbard wasn’t the only intellectual that Heath had an influence on. In fact, it was Heath’s own grandson, Spencer MacCallum, who would go on to develop Heath’s ideas more. MacCallum, an anthropologist, first espoused his ideas in the book The Art of Community. Though he would go on to expound on these ideas in the book Economics and the Spiritual Life of Free Men: Re-Imagining Our Emergent World Society.

It is MacCallum who coined the term “entrepreneurial community.” In his book, Duke discusses how MacCallum identifies two types of private or “proprietary communities” that can fulfill the functions of the state: (1) subdivisions; and (2) entrecomms.

Subdivisions are relatively familiar concepts and function similarly to contemporary housing subdivisions or condominiums. These have privately owned spaces and communally owned spaces administered by an elective body chosen by the owners of the private spaces within the community, just like your condo’s homeowners association. Entrecomms on the other hand function differently. In the case of an entrecomm there is a single owner who leases or rents out all of the different spaces, commercial or residential, and also maintains the common spaces. There is no elected body, only a private business that owns, maintains, and leases property, as well as providing public services. All of this is paid for by the rent from the lessees.

Massimo was deeply inspired by the views of Spencer Heath and Spencer MacCallum, and if you want to get a better understanding of exactly where Massimo is coming from, it is worth reading Duke’s book. It is also important to note that Massimo had a close personal relationship with MacCallum prior to the latter’s death in 2020. This is a close friendship that he shared with Joyce Brand.

Joyce Brand is one of two non-Honduran residents in Morazán, and she has a colorful history. She’s in her seventies, but looks at least 15 years younger, though she has recently started using a motor scooter to get around. Originally nudged toward libertarianism after reading Atlas Shrugged as a 17-year-old, she remained largely apolitical until she started a second career as a feature film editor in Hollywood in 2000. It was around this time that she began to attend dinner meetings with libertarians and ultimately became a delegate for California to the 2000 Libertarian Presidential Convention. It was here that she was exposed to the more radical voices in the libertarian movement including Mary Ruwart and Butler Shaffer, the latter of whom she later became personal friends with. This exposure to the anarcho-capitalist side of the liberty movement caused Joyce to delve more deeply into various libertarian writings. Ultimately, after reading Ludwig von Mises’ Human Action: A Treatise on Economics, Joyce began to call herself an anarcho-capitalist, though she now identifies herself as a Voluntaryist.

Through her involvement in the liberty movement, Joyce became acquainted with Spencer MacCallum and ultimately found herself in Mexico helping to edit Economics and the Spiritual Life of Free Men. Ultimately, Joyce played such a major role in the drafting of the book that she earned a position as a co-author. It is through this friendship with MacCallum that Joyce also became friends with Massimo. After assembling MacCallum’s archives and delivering them to Universidad Francisco Marroquín following MacCallum’s death in 2020, Joyce moved down to Morazán to live in a real entrecomm.

The City

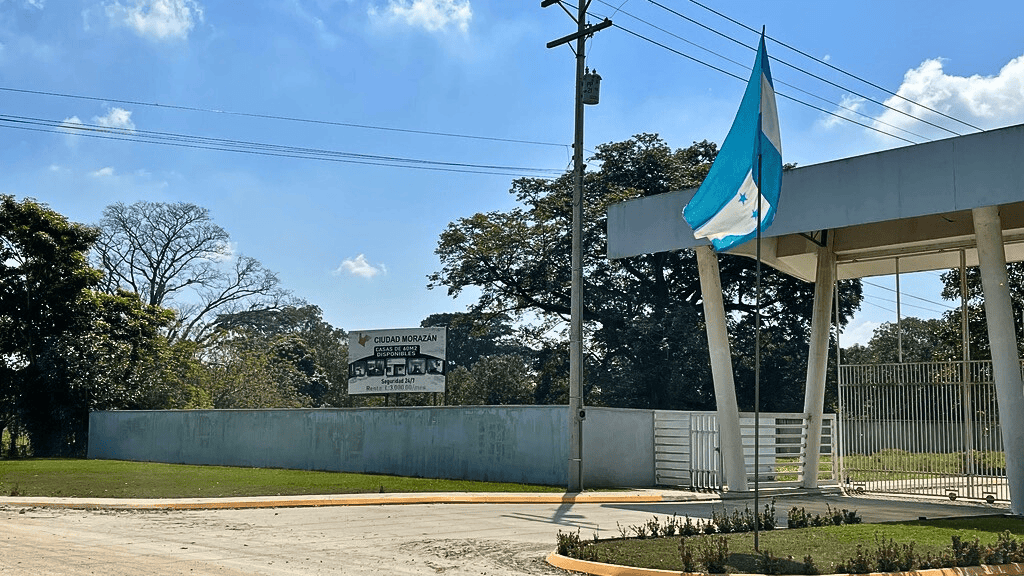

Ciudad Morazán is named after Francisco Morazán, the former Head of State of Honduras and President of the Federated Republic of Central America, and a liberal reformer who introduced the freedoms of religion, speech, and press to his country. He is a fitting namesake for the city that Massimo has modeled as an entrecomm.

Massimo came to know about entrecomms through his personal relationship with MacCallum. MacCallum and Massimo first met at an event at Universidad Francisco Marroquín (UFM), a university located in Guatemala City, Guatemala that espouses pro-market and pro-freedom principles. Massimo was taken by MacCallum’s idea of entrecomms. His mind primed with MacCallum’s model of governance and Honduras having the ZEDE law in place, Massimo was almost ready to take the leap and start a community of his own. Ultimately, what pushed him into doing so was the successful start of Próspera.

As the first ZEDE to be founded in Honduras, Próspera played a critical role in inspiring Massimo to start his own ZEDE. First, Massimo was able to watch Próspera in action for a couple of years prior to starting Morazán. This showed that it could actually be done. Unfortunately, having a law in place that enables something to be done is often not enough. Starting a new special economic zone is risky, especially with an untested law, but Próspera took the risk and showed other entrepreneurs that it was possible. Second, Próspera pioneered a significant amount of the legal documentation that must be done in order to incorporate a ZEDE. This includes a charter, bylaws, and regulations. Massimo is very open about the fact that he looked at the regulations that Próspera had adopted, liked what he saw, and adopted many of the regulations verbatim when they suited his purposes. However, it must be noted that CCI did provide comments and suggested revisions on some of his regulations prior to those regulations being adopted.

As mentioned earlier, Massimo had first looked into seeing if he could start his entrecomm as a district within Próspera. Why didn’t he ultimately decide to do so? For two reasons: first, he learned that he could start his own ZEDE with relatively little friction; and second, he could locate his project in an area that had a larger share of his target market.

Massimo’s target market is those Hondurans at the entry level of the Honduran middle class. This largely means those working in services and light manufacturing. People like Katherine Villeda are exactly the kind of person that Massimo is targeting. In her mid-20s, Katherine is originally from San Pedro Sula. Currently, she works at a call center. This job places her squarely in the Honduran middle class. People like Katherine, who work at call centers, and those who work in factories called maquiladoras, have the kind of stable jobs that provide the suitable income that defines Massimo’s target market. Importantly for Massimo, this market is large enough that he believes creating communities for them is economically lucrative. While Morazán is initially targeting the local economy and the blue-collar families working in the area, he believes that in the medium term, the community will develop organically in a way that attracts higher-income families and more sophisticated employers, such as those in the business service industries.

However, Massimo is not only creating communities for this particular demographic of Hondurans because he thinks that he can make a profit doing it. Importantly, he is doing it in part because he wants to provide these people with quality alternatives to what they otherwise would have to choose from. When he looks at the world’s middle class and working poor, he sees people without alternatives to bad governments. The world’s wealthy, he says, can choose to pick up and move to a country that will treat them better. However, the developing world’s middle class and working poor are akin to medieval serfs. They are serfs because, outside of dangerous illegal migration, they have no way to choose a jurisdiction that will treat them better. Massimo wants to provide these purported serfs with a real alternative.

While discussing his target market, Massimo fumes. Up to 10% of Honduras’ population is living in the United States, he tells me. Most of them illegally. The worst part, he says, is that many of those people are Honduras’ most entrepreneurial, which causes serious long term damage to Honduras’ economy. He goes on to say that the number of Hondurans leaving for the US has increased in recent years, you can tell that this is the case because the remittances sent back to Honduras from the US have increased substantially. He’s upset that ordinary Hondurans have no prospects besides a treacherous journey north to live illegally in the US or limited opportunities at home. I spoke to one Morazán resident who told me that she has five family members in the US, all illegally, but that she has not gone herself as she is afraid of the treacherous journey.

Once he decided that he wanted to give a shot at starting his own ZEDE, Massimo went about recruiting a team. Massimo specifically asked Diego Zúniga, whom Massimo knew for over a decade and knew his involvement in the liberty movement, if he was interested in going to work with him on the ZEDE. Diego was. So, fresh out of college and an internship at the Cato Institute, Diego went to work for Massimo’s pharmaceutical company. For a few months, Diego got some practical experience in business and management prior to going to work on the ZEDE project.

During this time, Massimo was engaged in negotiations to incorporate the ZEDE. As a part of this process, he had to give a series of presentations to relevant government officials. In these presentations, he had to provide a plan for the ZEDE that was within the legal scope of the ZEDE law. Over the course of this process in his presentations, he kept lowering the tax rate that he said his residents would have to pay to the ZEDE operator, as the ZEDE law requires that residents pay an income tax to the ZEDE operator, part of which is then remitted to the Honduran government. At first, Massimo was unsure whether or not the government officials that he was presenting to were noticing this progressive reduction in the proposed income tax rate that he would collect, but finally, he was called out and told that he couldn’t have a lower than 5% income tax. This didn’t bother him though, as this was significantly better than he initially thought he would get. So, while Morazán’s residents aren’t solely restricted to paying rent alone in exchange for the services that Morazân provides as in the truest form of the entrecomm model, Massimo is still happy with the outcome. As Massimo related this story he boasted that he never bribed anyone through this process and that everything was done above board. This is no mean feat when building a real estate project in the developing world.

In order to provide a governance alternative to his target market, Massimo had to put his ZEDE in the right location. Ultimately, the right location was found just outside of the northwestern city of Choloma. Choloma is a manufacturing powerhouse in Honduras with numerous maquiladoras. It is also the country’s third largest city, with a population of over 200,000. So, these two factors of the right economic sector and population size made the outskirts of Choloma a great location to start scouting for sites to establish a ZEDE. Diego first helped get the project running by being a team member on the team conducting market research in Choloma to ensure that the demand for what Massimo planned to build was there.

It was.

With the assistance of a real estate agent, Massimo and his team looked at several properties outside of Choloma. However, the 24 hectare site that they eventually selected was just about perfect. Once the site was selected and the land purchased, Massimo began to build. though additional land was later purchased in expectation of an expansion. On the initial 24 hectares, which encompasses all of the built-out infrastructure today, Massimo planned for 4 warehouses and 64 homes. Massimo says that he is building residential solutions that are affordable to people making US $350-400 per month, which are the typical salaries in the area. These solutions come in the form of 60 square-meter, two-bedroom townhouses that rent for US $120 dollars. He also had to build water and sewer systems and connect the site to the state power grid, which he contracted with to provide electricity to Morazán. This entire site is surrounded by a wall, as required by the ZEDE law. This is done in part as a security measure to prevent smuggling as ZEDEs are special customs areas under Honduran law, and therefore have their own requirements for import and export.

Diego was for a time the “mayor” of Ciudad Morazán. While the ZEDE law requires a Technical Secretary, a role filled by an attorney named Carlos Fortin, and this job is the most analogous to a mayor in the legal sense, Diego was the first person to fill a sort of community manager role on the ground in Morazán. In this role, it was Diego who interacted with the community on a daily basis. Due to this on the ground day-to-day function, he began to be called the mayor.

Diego developed a routine when he worked as the mayor of Morazán. He would get up in the morning, take a stroll around the houses, and chat with any of the residents that were there. While doing this he would take stock of any problems to report to the maintenance department. Then he would also deal with things like garbage collection or any issues that were brought to him by the residents. During the rest of the day, Diego also did things like accounting for the operating companies of Morazán, sending invoices to residents, managing the website, taking new pictures for marketing, general web maintenance, and searching for new residents. Diego also worked with the security company that had been contracted to provide Morazán with private security. Through all of this, Diego and the other Morazán staff were careful to talk to the residents and get their feedback on the perceived quality of life in the community.

Joyce is one of two foreign residents of Morazán. The other is her husband Alex Ugorji. Alex, 29, is originally from Cambridge, Massachusetts. He got into libertarianism late in high school prior to attending Middlebury College in Vermont. After he graduated he taught English in China for a year before attending Stanford for his master’s degree. Once he finished that he ended up on Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands Territory. As a US federally administered territory, the Northern Mariana Islands have a unique position in American law, which Alex sought to use to promote libertarian projects including some related to cryptocurrency. However, the 2020 COVID pandemic put a damper on his plans, and he eventually found his way to the most libertarian place that he could find, Ciudad Morazán.

Currently, Alex functions as the chief promoter of Morazán. He accompanies Massimo to relevant events, as well as going to events on his own, in order to build support for Morazán in various ways. However, just to say that Alex is Morazán’s chief promoter is selling him short. Like Massimo, he is a natural entrepreneur, and his various business ventures are a constant source of discussion and occasional jokes among Morazán’s residents. Alex has, among other things raised cows, provided low interest loans, and rented out solar panels. He says that he does so many things because they are so easy to do in Morazán. Alex provided me with the most interesting insight into Morazán. He said that the brilliance of Morazán is that, “It is a libertarian city without any libertarians.” While the fact that both he and Joyce live there somewhat dampens this assertion, it’s broadly correct. The incentive structure in place in Morazán encourages the residents to endear themselves to the community.

Functionally, what does it mean to endear yourself to the community in Morazán, and what are the incentives that encourage this? As an entrecomm that only leases to residents and does not sell property, Morazán has the power to choose to not renew a resident’s lease if they behave badly. As a standard residential lease is for a 3-month term, bad actors quickly leave. Though Massimo tells me that they haven’t had to either evict anyone or choose to not renew a lease, yet. So far, if a resident hasn’t been a good tenant or good neighbor they have felt that they don’t belong and have moved out on their own, thereby frontrunning any potential disciplinary action. Additionally, due to the fact that Morazán’s staff does such a good job keeping in touch with Morazán’s now roughly 140 residents, the administration can easily determine who is causing problems and who is a good community member. Furthermore, this structure invites residents to behave in a way that causes their neighbors to like them, and want them to stay as members of the community. Thereby encouraging kindness, entrepreneurship, and overall prosocial behavior.

However, the right incentives don’t always remove problems on their own. In one incident, a group of people that Alex came to call the “poopitrators” would walk their dogs through the community and not clean up after their pets. In this case, Morazán’s staff decided that it wasn’t enough to talk to the dog owners to get them to correct their behavior, but also that Morazán should have a dog park, which was quickly installed. During this time Morazán was successful, with the four warehouses rented out and generating substantial revenue, the ZEDE was profitable, the homes were being rented out, and things were looking good.

Unfortunately, this initial success wasn’t to last. In November 2021, the leftwing Libre party beat out the incumbent right leaning National party to win the general election. One of Libre’s leading issues was the repeal of the ZEDE law, which it was able to implement in April 2022. As the election results came in and it became increasingly clear that Libre would win, Massimo told Diego that he would understand if he decided to move on. However, Diego stuck it out at Morazán for another year and a half, but ultimately chose to leave in March of 2023 in order to advance his career. He currently works for the Adrianople Group. With this political environment, Massimo decided to pause his investments in Morazán out of fear that the business environment in Honduras would sour too much to be able to operate the ZEDE effectively, or even that Morazán might risk expropriation by the government.

Yet, not all hope is lost. Próspera has been engaging in some serious litigation with the Honduran government. Between Honduras’ bilateral investment treaty with the US, Próspera’s investor protection agreements with the Honduran government, and a few other legal issues, Próspera has a fairly good case. Should Próspera be successful in its litigation, it will also benefit Morazán. So far the existing ZEDEs have been able to continue to operate, though no new ones have been able to be established. Once the initial tumult of the repeal happened, and the darkest hours of the COVID pandemic were over, the likelihood that the ZEDEs would have a fighting chance began to look better. So, Massimo has begun construction again.

The resumption of construction isn’t the only bright spot. After Diego left, the job of mayor passed to a few different individuals, none of whom filled the role as well as Diego. For months Alex and Massimo were encouraging Morazán resident Ursula Frederick to take the job. In her early 30s, Ursula is a former medical student who dropped out of her program to pursue a career in the cruise industry. She worked on cruise liners for the better part of a decade. During this time she traveled to 69 different countries and tells a harrowing story about nearly being stranded ashore in Namibia when she almost didn’t make it back to her ship in time from a medical appointment. After she became pregnant with her now 4-year-old daughter, Ursula left the cruise industry.

Ursula is a natural for the role of mayor. She is friendly, kind, entrepreneurial, and knows all of Morazán’s residents and how their lives are going. This all comes naturally to her. Most recently, Ursula has been working as a scheduler for a gastroenterologist in the US. Prior to that, she ran a small cafe that she had to close after a power outage destroyed much of her stock. Prior to that, she ran a small clothing store, but it was hard to operate as she had to keep paying the “war tax” to the gangs in Choloma. Eventually, the war tax devolved to gang members coming into her store and taking whatever they wanted. This was unsustainable. At that time, Ursula was living in a house that she owned in Choloma, but with the presence of gangs, she didn’t feel safe there. Looking for safer places to live, she found Morazán on Facebook. She decided to move in in May 2023 and lease out her home Choloma, which she still owns. Living in Morazán introduced her to Alex, and the two started doing business together. Alex boldly claims “I made Ursula.” However, a short chat with Ursula is more than enough to start to see her virtues including her entrepreneurial streak.

Intrigued by the opportunity to become the mayor of Morazán, Ursula was initially hesitant to accept the job because of Massimo’s reputation for shouting at employees. After a conversation with Alex and Massimo, the fiery Italian promised that he wouldn’t yell at Ursula (it is important to emphasize that Massimo’s shouting comes from a place of passion for providing his customers with quality service, not out of a desire to verbally abuse his employees). So, Ursula accepted the job, and since March of 2024 is the mayor of Morazan.

With construction once again underway and a new mayor in place, things are looking up for Morazán. While the outcome of Prospera’s litigation remains uncertain, a general election is once again on the horizon in Honduras. All of this points to a strong chance that the ZEDEs will continue to function as they have been, and that should the opposition party win the next general election the ZEDE law might even be reinstated. Massimo wants to build Morazán up to its initial planned population of 10,000 people. He says that if he hadn’t had to stop construction in 2021 he would likely have several thousand residents in the city.

However, this isn’t the end of Massimo’s vision. He believes that in order to maximize liberty and customer experience, there needs to be a wider system of entrecomms. The real liberty that entrecomms provide, says Massimo, is not in the individual communities, but in a wider competitive ecosystem of entrecomms. Under a purely market based approach, individuals would engage in relationships primarily via contract. Though, says Massimo, having every person select their governing law isn’t natural, and it is much more natural to choose a place to live in a market based system and use the governing law of your chosen home. So, Massimo wants other entrepreneurs to create their own entrecomms and compete to provide people with the best services possible. In this vision Massimo sees less than 5% of GDP being spent on governance services (as of this writing the US spends over 32% of GDP on government). Massimo views the 1.5-2 billion of the world’s low income people as his primary market. These people can emigrate from their homes, but they effectively can’t immigrate to other countries, and Massimo wants to provide these people with an alternative to bad and expensive governance. Furthermore, Massimo thinks that libertarians are foolish to focus on building liberty only for libertarians. He says that he respects the Free State Project, but that by focusing only on libertarians the potential success of the project is limited. Massimo instead will, just like he has done in Morazán, create communities where the incentive structures make people act like libertarians whether they know it or not.

While some people might find Massimo’s plans to build a system of entrecomms to be a little outlandish, his ideas might be some of the most tame in the innovative governance space. Fundamentally, Massimo is building a community for the honest, hard working middle class of a developing country. The project most similar to his in location and structure, Próspera, is focused on attracting tech and biotech companies to an island most famous for its resorts, in an effort to engage in regulatory arbitrage with the hyper-regulated economies of the US and Canada. Both of these efforts are substantially less cutting edge than the idea of the network state, which has taken the innovative governance space by storm in the past couple of years. Fundamentally, Massimo’s desire is to show that the entrecomm model can outcompete the status quo governance offering, and he is doing it in a way that attracts customers.

Final thoughts on Ciudad Morazán

Overall, Morazán has been a success. Importantly, Massimo has proven that the model of entrecomms works in practice, and he is confident that he can replicate it himself. Not only that, but Morazán is a model that can be replicated elsewhere, and not just in Honduras, but anywhere in the world that will let entrepreneurs try it. However, Morazán would be more successful if it hadn’t been held up by the political situation in Honduras. This key issue of political instability will be the bane of many new city projects in the developing world and is likely the key weakness of the model. This model thrives in developing countries with weak governing institutions that can be strengthened with innovative jurisdictions like ZEDEs, but it is the same relatively weak institutions that provide the opportunity for experiments in governance that also pose the biggest threat to it. Fundamentally, these types of projects need to find governments in a sweet spot of struggling to provide effective governance on their own, but stable enough to not whiplash and seek expropriation of projects after the next election cycle.

Finally, if you’re plugged into the idea of charter cities or innovative governance generally, you’ve probably read, or at least heard of Neal Stephenson’s book Snow Crash. In this prescient sci-fi novel, the United States and most of the world’s other governments have largely disintegrated and the world is a neo-medieval tapestry of competing power centers. Stephenson has most people in his fictional future America live in so-called “burbclaves.” Effectively, these are gated communities that operate under their own law, most of them on a franchise model, with the different corporations competing against each other based on the services and lifestyle that they offer. To the outside observer, this sounds substantially like entrecomms, and you might be wondering if Massimo was inspired by the book. Well, I asked, and it turns out that Massimo has not read Snow Crash.

Booklist

Over the course of my short stay in Morazán, numerous books came up in conversation, more than even normally come up in CCI’s notoriously nerdy office. Here is a list of them for those interested:

- Belle Isle Detroit’s Game Changer by Rob Lockwood

- Entrepreneurial Communities by Calvin Duke

- Economics and the Spiritual Life of Free Men: Re-Imagining Our Emergent World Society by Spencer Heath (Author), Joyce Brand (Author), Spencer MacCallum (Editor), Zach Caceres (Introduction)

- The Art of Community by Spencer MacCallum

- Man, Economy, and State by Murray Rothbard

- Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson

- The Diamond Age Neal Stephenson

- Charter Cities Atlas by AG and CCI

- The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert Heinlein

- Pioneering Prosperity: The Morazán Model for Entrepreneurial Governance by Joyce Brand (awaiting publication)

¹ Your author wasn’t able to get ahold of Mr. Duke leaving him to ask himself: “Who is John Galt? Who is Satoshi Nakamoto? Who is Calvin Duke?”