Introduction

The defining story of the African continent in the twenty-first century is of rapid urbanization, with cities emerging as important centers of economic activity and social transformation. However, too often we hear only about the megacities of Africa, such as Lagos, Kinshasa, Addis Ababa, Nairobi, and Dar es Salaam. We hear less about second- and third-tier cities that are filling critical economic niches in the continent’s economic modernization, which are growing rapidly with new migrants and have their own unique challenges and relationships to national African governments. We read and hear even less about African megalopolises, physical urban agglomerations that stretch over hundreds of miles and look and function as one connected urban ecosystem wherein distinct metropolitan areas feed into each other. Even when megalopolises are discussed, it is usually in the context of the megacities within these blocs, not the second-tier cities that keep the urban systems functioning.

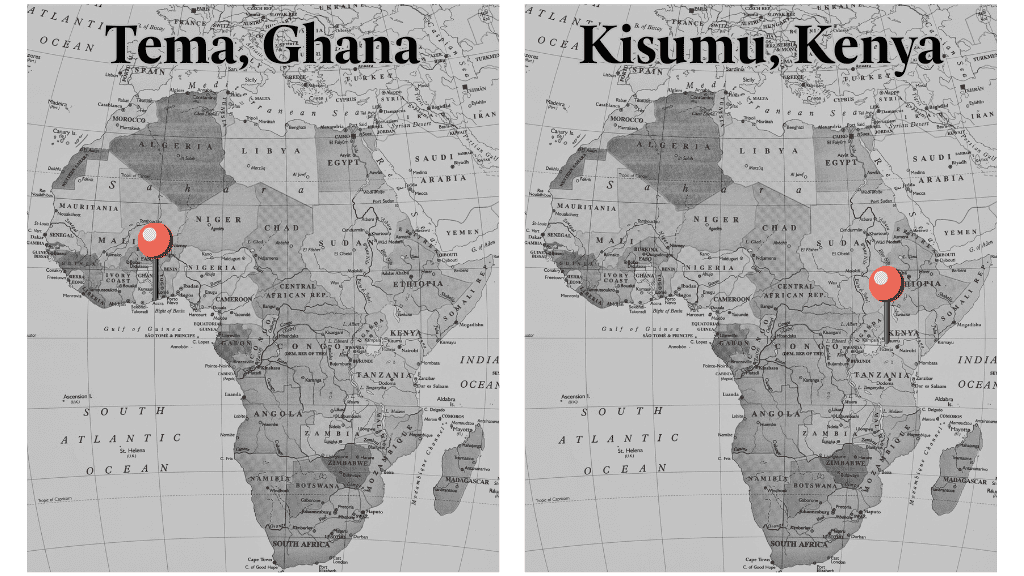

Two such second-tier cities serving as key parts of urban metroplexes are Kisumu, Kenya (in East Africa) and Tema, Ghana (in West Africa). Kisumu and Tema are each representative cities within two emerging metroplexes on opposite ends of the continent.

The West African metroplex, or the “Gulf Of Guinea Megalopolis,” is a rapidly growing urban agglomeration that extends across the coast of the Gulf of Guinea from Abidjan, the economic hub of Côte d’Ivoire, to Lagos, the largest city and commercial center of Nigeria. Some would argue it extends even further across most of the southern Nigerian coast, incorporating cities like Port Harcourt. The metroplex includes several important cities in the region, such as Accra in Ghana, Lomé in Togo, and Cotonou in Benin, among others. The population of the West African metroplex has grown rapidly in recent decades, reflecting a regional trend of urbanization and rural–urban migration that have made it one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the world. A lot of this growth consists of intense urbanization in Nigeria, which is poised to become the world’s third most populated country by 2050. While no regional census has been conducted, the population in the metroplex is likely between 25 and 40 million people, given the figures for its major cities.

The East African metroplex is a rapidly growing urban agglomeration that extends from Nairobi, the capital city of Kenya, to Kisumu, a major city in western Kenya, to Kampala, the capital city of Uganda, and Kigali, the capital city of Rwanda. The metroplex also includes Goma and Bukavu in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This region is bound together by the promise and potential of the East African Community (EAC), a bloc of countries seeking to regionally integrate their economies and that have vague but never-quite-settled plans of an eventual federation or confederation. While the Gulf of Guinea Megalopolis is also under the purview of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the EAC is a far more focused and cohesive bloc with stronger powers and a higher potential of becoming a federative or confederate union.

From a societal transformation perspective, these two metroplexes are currently some of the most exciting places in the world to study. Both the urban research and business communities should more closely evaluate the dynamics playing out in these regions, which are constantly being remade.

Kisumu is located on the shores of Lake Victoria, one of the largest freshwater lakes in the world. The city, which expanded organically under British imperial rule in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, has become a major commercial and transportation hub that serves as a gateway for trade among the EAC states. Its economy is driven by fishing, agriculture, and manufacturing, and it is home to several institutions of higher learning.

Tema, meanwhile, is a coastal city situated in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. The port of Tema, one of the largest and busiest ports in West Africa, serves as a gateway for imports and exports from and to other West African countries. A planned city, Tema was created in the 1960s to serve as the tentpole for Ghana’s broader industrialization. Local industries include manufacturing, textiles, food processing, and export processing, which provide job opportunities and contribute to the national economy.

The experiences of Kisumu and Tema reflect the challenges and opportunities of urbanization and economic development in Africa. The two cities have experienced significant population booms and economic growth since the 1960s, driven by urbanization and migration. However, they have also faced associated challenges, such as the proliferation of informal settlements, inadequate basic services, and infrastructural issues.

This paper compares the experiences of Kisumu and Tema, highlighting similarities and differences in their geography, population growth and migration, economic development, and challenges of urbanization. The lessons learned from these two cities can inform policies and interventions aimed at promoting sustainable urban development and improving the lives of urban residents in Africa.

Two Cities, One Destiny?

Kisumu’s port on the shores of Lake Victoria and Tema’s on the Gulf of Guinea play crucial roles in their respective countries’ trade and economic activities, facilitating the movement of goods and connecting their countries to regional and international markets. Both of their economies rely heavily on associated industries such as fishing, agriculture, and small-scale manufacturing.

However, the differences between the two cities start with their ports, their central feature. Tema was designed by Ghana’s first prime minister and president, Kwame Nkrumah, to be the country’s chief seaport and associated industrial town. As a result, the city hosts Ghana’s primary gateway for international trade and one of West Africa’s largest ports. The port has been significantly expanded and modernized in recent years, increasing its capacity and efficiency. It stretches over 3.9 million square meters (1.51 square miles) and can process over 3.5 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs)—i.e., standard shipping containers—annually. The port itself now handles over 70 percent of all of Ghana’s trade, making it Ghana’s lifeline to the world.

On the other hand, Kisumu has a smaller inland port on Lake Victoria that mainly facilitates regional trade within East Africa, connecting Kenya to neighboring countries such as Uganda and Tanzania, as well as facilitating trade to South Sudan and DRC. The port of Kisumu has not experienced the same level of expansion and modernization as Tema’s, which limits its capacity and efficiency: It can only process up to 15,000 TEUs annually. This reflects the natural economic gap between the two cities resulting from their port size.

Because it hosts a major port, Tema is furthermore home to a large industrial area, with numerous factories and manufacturing facilities that contribute significantly to Ghana’s economy. In contrast, Kisumu’s industrial activities are relatively small-scale, focusing on agriculture, fishing, and smaller manufacturing operations.

Kisumu and Tema have both also experienced rapid urbanization and population growth since the late 1950s and early 1960s, driven by migration from rural areas and the expansion of economic opportunities in these cities. Tema had a population of around 15,000–20,000 residents in the 1960s, while Kisumu had around 25,000–30,000 residents.¹ Both are now modern cities where hundreds of thousands of people live. This growth has led to significant urban challenges, such as inadequate housing, infrastructural issues, and environmental concerns. In particular, both cities have seen the growth of informal settlements characterized by a lack of basic services, poor housing conditions, and overcrowding. These settlements present challenges related to sanitation, access to clean water, and public health. They also prevent both Kisumu and Tema from being seen as “lifestyle cities” like Nairobi and Accra, which are better able to attract tourism.

However, they differ in terms of the scale of the challenges they face regarding rapid urbanization. For instance, Kisumu has a higher prevalence of diseases such as HIV/AIDS and malaria. In contrast, Tema’s challenges are more focused on managing the city’s growth and addressing infrastructural and environmental issues associated with its expanding industrial base. This cannot be explained by an economic difference between Ghana and Kenya, which have a similar gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Rather, it is likely because Tema is far closer to the capital, Accra, and is Ghana’s chief seaport while inland Kisumu is farther from Nairobi and has fewer maritime connections.

In summary, Kisumu and Tema share similarities as port cities in rapidly urbanizing regions that are facing challenges related to population growth, informal settlements, and economic development. However, differences in regional context, port size and capacity, industrial development, and the nature of their challenges set them apart.

Kisumu’s History

Before the arrival of European settlers in the region, the area around present-day Kisumu was inhabited by various indigenous communities, predominantly the Luo people. The Luo community engaged in fishing, farming, and herding in the region surrounding Lake Victoria. The area was known for its rich natural resources, fertile land, and access to water, making it an attractive location for settlement and trade.

In the late nineteenth century, European powers began to explore and establish their presence in East Africa. The British Empire, in particular, sought to extend its influence in the region, both to protect its interests in the Indian Ocean and to counter the expansion of other European powers such as France and Italy. In 1888, the British East Africa Company was granted a royal charter to administer and develop the territory of British East Africa, which included present-day Kenya and parts of Uganda and Tanzania. In their efforts to establish control and facilitate trade in the region, the British set up trading posts and forts around Lake Victoria. The area that became Kisumu was identified as a strategic location for such a post due to its access to the lake and its position along the trade routes connecting the interior of East Africa to the Indian Ocean coast.

The development of Kisumu, which the British initially called Port Florence, began in earnest at the turn of the twentieth century with the construction of the Uganda Railway, although the initial settlement of the town far predates the arrival of the British. The railway project aimed to link Mombasa on the Kenyan coast to Lake Victoria, opening up the region for trade and further colonial expansion. Its primary objective was to facilitate the transportation of goods and passengers between the coast of British East Africa (Kenya) and the interior, particularly Uganda, which was considered the “Pearl of Africa” due to its abundant resources and fertile land. It also involved the importation of masses of Indian laborers, who grew to become an important ethnic minority.

The establishment of Port Florence as the railway terminus on the shores of Lake Victoria laid the foundation for Kisumu’s growth as an important urban center and trade hub in East Africa in the early twentieth century. During this period, Kisumu became a center of administration and commerce, with the British colonial government establishing offices and institutions to oversee the region’s affairs. The influx of laborers, traders, and colonial administrators led to rapid population growth and urbanization. The port enabled the movement of goods such as cotton, coffee, and tea from Uganda and the Kenyan hinterland to Mombasa and other international markets. Its facilities were expanded and modernized to accommodate the increasing volume of trade and the changing demands of the colonial and global economies. The town’s strategic location on Lake Victoria and its role as a transportation hub attracted investment and fostered the growth of businesses and industries, particularly those related to trade, transportation, and logistics.

As the city grew, a clear divide emerged between the planned European and Asian quarters and the African neighborhoods. Africans were relegated to the outskirts of the town, where they established informal settlements due to their limited access to land and resources. Following Kenya’s independence in 1963, Kisumu experienced rapid population growth, driven by migration from rural areas and neighboring countries. And although many British settlers left Kenya, Indians—who had played a significant role in Kisumu’s trade and commerce during the colonial period—continued to contribute to the local economy, although their influence diminished as African entrepreneurs emerged in various sectors.

The city’s population more than doubled from around 50,000 in the 1960s to 110,000 by the 1970s. This influx of people exacerbated the existing housing shortage, prompting the expansion of existing informal settlements and the formation of new ones. Meanwhile, the 1971 coup in Uganda that brought Idi Amin to power led to an influx of refugees into Kenya, some of whom settled in Kisumu. Subsequent economic challenges and stagnation continued to negatively affect urban development and investment in infrastructure even as Kisumu’s population continued to grow, reaching around 185,000 by 1990. The city’s informal settlements expanded further as the demand for affordable housing continued to outstrip supply.

In addition, the 1976–80 collapse of the East African Community—which had been established in 1967 to promote economic cooperation—led to the fragmentation of regional trade and transport infrastructure. Under the British Empire, regional norms on taxation, trade, and relations between the former colonies had been stable. But as independent states locked in competitive postures, the reduced volume of trade negatively impacted Kisumu’s development and growth as a lakeside port city. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, escalating political tensions between Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania continued to affect trade and transportation along Lake Victoria. These developments contributed to the decline of the port city in ways that still affect the modern Kisumu of today.

The railway system, which was a vital link between Kisumu and other parts of Kenya and Uganda, also faced numerous challenges during this period. These included inadequate maintenance, aging infrastructure, and mismanagement, which led to a decline in its efficiency and reliability. As a result, the transportation of goods to and from Kisumu’s port became more difficult, further reducing its importance as a regional trade hub. This challenge continues to the present day: While the modern Kenya Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) connects Mombasa to Nairobi, it has proven challenging to secure financing to extend it out to Kisumu, and then by extension to Uganda. This means Kisumu has been unable to replicate being both a vibrant railway terminus and an efficient lakeside port, which undergirded its initial prosperity.

The collapse of the EAC, the declining railway system, and Kenyan economic stagnation in the 1980s and 1990s under the Daniel arap Moi government all colluded to send Kisumu into hard times. However, this is not the end of Kisumu’s story.

Kisumu Today

Since 2000, Kisumu has been a city partially reborn. Part of this is due to the re-establishment of the East African Community in 2000, with Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania deciding to patch up their major differences and recommitting to regional cooperation. This created a favorable environment for increased trade and investment in the region, positively impacting Kisumu’s port. Along with this development came the decision to create the Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC), an EAC institution that aims to promote sustainable development around Lake Victoria. Established in 2001, the LVBC has facilitated various projects and initiatives to improve transportation infrastructure in the area. These two trilateral organizations have boosted confidence in Kisumu’s potential future.

On the back of these broader institutional developments, the Kenyan government, in collaboration with regional partners, launched efforts in the 2010s to revive and modernize Kisumu’s port for around 3 billion Kenyan shillings ($22 million). The revitalization project, completed in 2019, involved dredging the port, constructing new berths, and upgrading the port facilities. The upgraded port has increased its capacity to handle passenger traffic and cargo, including up to 15,000 TEU annually. This has facilitated an increase in regional trade, particularly with Uganda, to which transport costs have fallen by 30 percent. The port now handles a variety of cargo, including fuel, agricultural products, and manufactured goods. This has positively impacted the local and regional economies by creating jobs and fostering economic development.

This reinvestment in Kisumu’s port has benefited the broader city. In 2015, the Kenyan government passed the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) Act, paving the way for setting aside land in Kisumu for an SEZ in 2021. This move aims to attract investment in industries such as textile manufacturing, agri-processing, and logistics, which can benefit from the port’s improved infrastructure and connectivity. Foreign companies that locate in Kenya’s SEZs also benefit from tax relief and special administrative processing.

The city has continued to attract new residents, not only from rural parts of Western Kenya but also—with the reintroduction of the EAC and greater cross-regional trade—from across East Africa. Burundians, Rwandans, Ugandans, and Tanzanians are all seeking to make a new life in the lakeside port city.

As demonstrated, the growth of the East African metroplex eventually reached a point where a lack of coordination dealt a harsh blow to certain second-and third-tier cities such as Kisumu. However, a renewed commitment to growth and cooperation can breathe new life into them. Ironically, modern efforts to foster a spirit of cooperation and economic growth could achieve what the British Empire had initially attempted, with Kisumu functioning as a kind of East African commonwealth city.

Kisumu still faces intense challenges around informal housing and a proliferation of shantytowns. Its diverse and dynamic informal settlements have a long and complex history dating back to the early twentieth century. Economic growth and urban governance in Kenya have just not been rapid enough, sophisticated enough, or esteemed enough to keep pace with waves of migration from rural areas and neighboring countries. While Kenya devolved a lot of power toward local governments in the 2010s, the newness and inexperience of these authorities—including the Kisumu County government—have still prevented them from forming a clear housing policy.

As the map below shows, a major chunk of Kisumu is dominated by informal settlements. This notably includes the largest settlement, Nylaneda, which is not too far from port facilities. These settlements are continuing to spread, complicating the process of constructing more sustainable housing on this land.

Some of the major informal settlements in Kisumu include:

- Nyalenda: Nyalenda is the largest informal settlement in Kisumu, with an estimated population of over 60,000 people. The settlement particularly lacks clean water, sanitation facilities, and healthcare and education services.

- Manyatta: Manyatta, with an estimated population of approximately 40,000 residents, is characterized by high population density and limited access to basic services.

- Obunga: Obunga is a smaller settlement of around 20,000 people. Like the other informal settlements in the city, Obunga faces challenges related to inadequate infrastructure, poor access to basic services, and land tenure insecurity.

Various initiatives have been implemented to address the challenges faced by these informal settlements. For instance, the Kisumu Urban Project, funded by the French Development Agency, has focused on upgrading infrastructure, expanding access to clean water and sanitation, and providing vocational training for residents. Additionally, the Kenya Slum Upgrading Program (KENSUP), launched in 2001 by the Kenyan government in collaboration with UN-Habitat, has aimed to improve living conditions in informal settlements across the country, including Kisumu. Despite these efforts, much work remains to be done to ensure that residents of Kisumu’s informal settlements have access to safe and dignified living conditions, as well as equal opportunities for social and economic development.

Kisumu stands at a crossroads between a glorious and storied past, a recent downturn, and a potentially vibrant metropolitan future—especially given its advantageous location by one of the world’s largest reservoirs of freshwater in the coming era of global water scarcity. Kisumu’s history demonstrates that it is vital for the city to maintain regional connections with its peers within the East African metroplex and for the Kenyan government to continue investing infrastructurally in its port, road, and rail infrastructure. Such efforts can help it grow from strength to strength and once again become a glorious lakeside city.

Tema’s History

Tema was a relevant city from the start. When Ghana achieved independence in 1957, President and Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah was intent on pursuing avenues of industrial growth. He decided one of the megaprojects he would pursue would be the creation of a new national port that would be a part of a broader planned economic community and an industrial hub for the new country. This port would be a central component of Nkrumah’s vision, serving as a catalyst for industrialization and trade.

The decision to build the new port at Tema was motivated by several factors, including the limitations of the colonial-era port of Takoradi, which was unable to accommodate larger ships and lacked the capacity to handle the growth in trade following Ghana’s independence. Tema was also strategically located close to Accra, allowing for easy transportation of goods to and from the capital and making it an important hub for economic activity and development in the region.

A deep-water harbor was constructed at Tema, enabling it to accommodate larger vessels and handle a wider variety of cargo. The establishment of the port also spurred the development of the city of Tema, which was created to provide housing and services for port workers and their families. Tema was designed as a planned city with a well-organized layout and modern infrastructure. Its growth was closely linked to the success of the port, which attracted both domestic and international investors.

The Tema port officially opened in 1962, becoming the main gateway for Ghana’s international trade and playing a vital role in the national economy during the 1960s and 1970s. It quickly surpassed the older Takoradi port in terms of capacity and trade volume, handling exports cocoa, gold, and timber, as well as imports of essential goods. During this period, the port underwent several expansion projects to accommodate the growing volume of trade and the increasing size of ships, including by upgrading the port’s infrastructure and building new berths, warehouses, and other cargo-handling facilities. The expansion of the port also attracted a range of industries and businesses to Tema, further driving economic growth and urbanization in the region.

Tema’s success had a spillover effect on the broader Ghanaian economy. The port’s growth helped stimulate demand for locally produced goods and services, creating employment opportunities both directly and indirectly. The increased trade facilitated by the port also contributed to Ghana’s foreign exchange earnings, which were vital for financing development projects and supporting the country’s balance of payments.

However, the 1980s and 1990s were marked by economic challenges in Ghana, as they were for most of the continent. By the early 1980s, the country was suffering through a period of coups and political instability, which had helped corrode the formerly healthy foundations of the state. This affected the performance of the Tema port and its role in the regional economy. High inflation, currency devaluation, and a decline in commodity prices led to a slowdown in trade and reduced government revenues. This, in turn, reduced infrastructure investments in the Tema port, which was already struggling to maintain its efficiency and competitiveness in the face of outdated equipment and facilities.

Despite these setbacks, the port continued to play a vital role in the regional economy, facilitating the movement of goods between Tema, Accra, and other parts of the country. It remained a key driver of economic activity, providing employment opportunities and supporting the livelihoods of many Ghanaians. The economic challenges of this period also led to the implementation of structural adjustment programs that aimed to address Ghana’s fiscal imbalances and stimulate economic growth. These reforms included liberalizing trade and implementing new exchange-rate policies—which had positive implications for the Tema port and its future development.

Tema Today

Tema’s port is a critical hub for Ghana’s international trade that relies on improvements to its infrastructure to maintain its efficiency and competitiveness. However, broader Tema is facing more difficult challenges as a second-tier city in a growing urban metroplex.

Tema’s economy is heavily reliant on the port and its associated industries, making it vulnerable to external influences on trade and economic growth. In addition, as a major exporter of raw commodities such as cocoa, gold, and timber, Ghana’s economy is sensitive to fluctuations in global commodity prices. This can directly impact the volume of exports passing through the Tema port—as can other changes in global trade patterns, such as shifting supply chains and trade disputes—affecting revenues and employment in the region. To mitigate the risks posed by price fluctuations and reduced trade, Tema can focus on diversifying its economic base and attracting investments in new industries and sectors.

The Tema port also faces growing competition from other ports in West Africa, such as those in Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo. Abidjan and Lomé in particular can process 2.2 and 2.1 million TEU annually, respectively, and can easily conduct overland trade from their ports to landlocked countries such as Burkina Faso, undercutting Tema’s market to a certain degree. To maintain its competitiveness, the port needs to continually invest in infrastructure, technology, and services that enhance its efficiency and attractiveness to businesses.

The rapid growth of Tema has also led to various social issues, including housing shortages, inadequate public services, and the proliferation of informal settlements. These settlements often lack access to basic amenities and contribute to public health concerns. As a planned town, Tema still has some sense of order in its design despite now hosting around 250,000 residents. However, just as Tema is a suburb of Accra, it has developed its own unique commuter town relationship with the massive informal settlement of Ashaiman, which is where many of the migrants and informal workers who depend on the city for an economic livelihood live. The settlement has grown rapidly due to its proximity to the Tema port and the industrial city, offering employment opportunities for residents. Although Ashaiman is now considered its own town, it developed symbiotically in connection with Tema, and the two districts form a mini metro area of around 600,000 people—about 340,000 of whom reside in this settlement. Ashaiman faces challenges such as overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and limited access to healthcare and education.

Addressing the social challenges in these informal settlements will require targeted investments in affordable housing, infrastructure, and social services. This includes improving access to clean water and sanitation, upgrading housing conditions, and providing better waste management and public health services.

Tema, like Kisumu, stands at a crossroads between its industrial past in the shadows of Accra and a potential future as a fully formed city in its own right.

Conclusion

Located in western Kenya and southeastern Ghana, respectively, Kisumu and Tema each have a rich history of economic and political development. Their rapid growth was fueled by the establishment of transportation infrastructure such as ports and railways, as well as the presence of foundational economic minorities such as British settlers and Indians in Kisumu.

These factors led to significant population growth and the development of various industries, which have contributed significantly to the economies of these cities. Moreover, as critical second-tier cities in expanding metroplexes, Kisumu and Tema play a role in driving regional economic growth and development by supporting industry and providing employment opportunities. In essence, these two emerging cities are vital to the economic development of their respective regions.

These cities have the potential to become even more influential in the future. Kisumu, for example, is part of the Lake Victoria Basin in the broader East African metroplex, which is undergoing significant changes and is projected to experience even more rapid growth in the coming years. The region conducts significant agricultural and fishing activities, which present an opportunity for the city to become a hub for agribusiness and food processing. As population outflows also continue from Nairobi, Kisumu is poised to grow only more important within East Africa.

Similarly, Tema is part of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area in the emerging “Lagajan” (Lagos–Abidjan) corridor. The region has a thriving service sector that is expected to drive economic growth in the city. Additionally, the Tema Industrial Area, which is home to several manufacturing companies, has the potential to become an even more significant industrial hub in West Africa.

As these cities continue to expand and evolve, it is essential to ensure that their growth is sustainable and inclusive. Second-tier African cities will either be where the African urban experiment lives and thrives over the coming century—or where it fizzles out in acrimony and disappointment.

¹ Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 1964. 1962 Census, Vol. 1. Nairobi: Ministry of Economic Planning and Development.