African cities are woefully underfunded, both in terms of public expenditure and infrastructure investments. As Africa further urbanizes – the region is expected to add 950 million people to its cities in the next 30 years – demand for public services and new infrastructure will grow. Consequently, local financial gaps will continue to widen if these cities do not find additional funding to accommodate new urban residents over the coming years. Currently, African cities are estimated to face a $25 billion annual municipal investment gap.

Africa’s local financial shortfall is especially stark when compared to cities in the West. To illustrate this global inequality, we created a dataset of financial data from the three most-populated US cities (New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles) and a handful of large sub-Saharan African cities with accessible data. The data shows that despite being larger and more populated, African cities have a much lower capacity to provide for their residents.

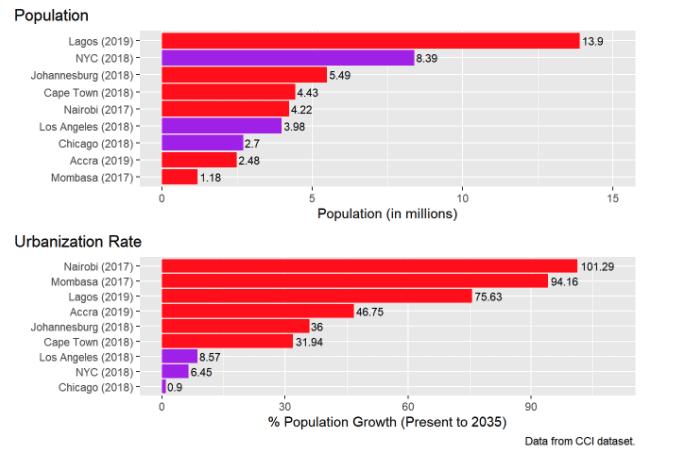

African cities in our sample tended to have a larger population and are expected to grow at a faster rate over the next 15 to 20 years than the three largest US cities. On average, our African cities had a population of 5.3 million people and an anticipated 15 to 20-year growth rate of 64%. In contrast, our US cities had a population of 5 million and an anticipated growth rate of just 5%.

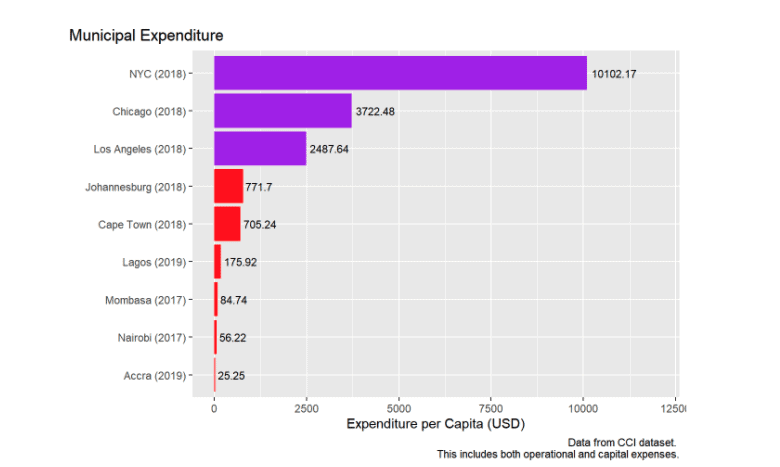

Despite these differences, African cities spend substantially less per resident than cities in the West. On average, the top three largest US cities spent $5,437.43 per resident compared to just $303.18 per resident in the included sub-Saharan cities. This translates into lower quality local public services, such as utilities, education, healthcare, and transit. As these cities grow, the global gap in municipal services will worsen.

The lack of public provisions and infrastructure in African cities is perhaps not surprising. Cities in the developing world find themselves in weak macroeconomic environments with low national GDP, and there is a limit to what they can achieve given these constraints. However, that doesn’t mean they can’t be improved. With better local governance and greater access to finance, these cities will be better equipped to handle their surging populations in the coming decades.

How do you improve municipal finance in Africa?

Cities generally fund their budgets in three ways. Their primary source of income comes from local taxes and service fees (e.g., electricity and water bills). Next is income from intergovernmental transfers. This includes grants from higher-level governments and, in the Global South, international financial organizations like the World Bank and African Development Bank. If these sources are not sufficient to cover a city’s budget, local governments may then try to take on debt through direct loans from banks or by offering municipal bonds.

In most cases, internally-generated income (i.e., taxes and service fees) is the most sustainable way to finance a city’s budget. This is because revenue directly scales to population changes. If the population grows, then so does the tax base. This is in contrast to intergovernmental grants, which can be dictated by national politics and are generally unresponsive to changes in local needs.

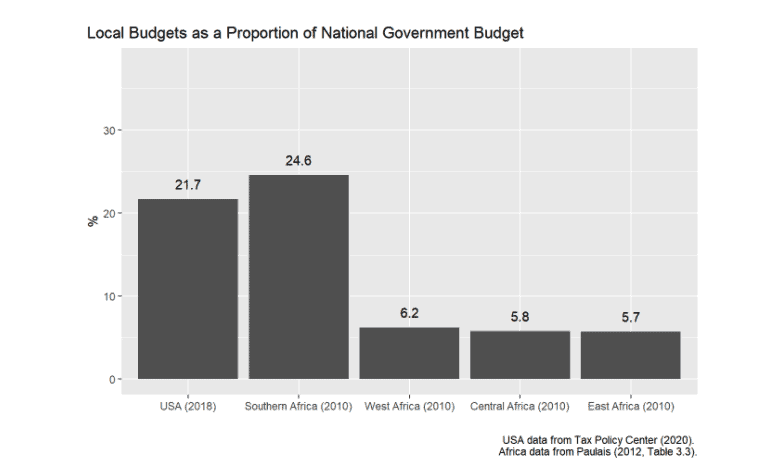

Compared to the West, sub-Saharan African cities derive a much smaller share of their budgets through own-source revenues. For example, in the US, local government budgets in aggregate were 21.7% as large as that of the federal government. However, local budgets were less than 10% of central government budgets in West, Central, and East Africa. This means that African cities are highly reliant on the financial decisions of higher-level governments in their country. The exception is Southern Africa, where local governments have comparable financial independence to that of the US. This is largely driven by South Africa, which deliberately decentralized fiscal powers to its cities in 2003.

African cities face two constraints in generating their own revenue. The first is capacity. While many countries in Africa allow their cities to collect taxes and fees, local governments often do not have the ability to enforce tax regimes. In some cases, they lack the administrative capacity to collect taxes, and in others, they do not have enough data to determine who to tax. Improving municipal administrative capacity should lead to more sustainable finances. This has been the outcome in the few cities that have experimented with capacity-building. Hargeisa, for instance, used GIS technology to survey taxable properties, and they saw a 250% increase in property tax revenue.

The other constraint is political. In most of Africa, lucrative sources of public revenue are controlled by the central government. One example is property, which is one of the most lucrative sources of revenue. In the developed world, property tax collection is largely the responsibility of local governments. In Africa, however, central governments often closely protect their right to property revenue. This is especially detrimental to the rapidly growing cities of sub-Saharan Africa, since they will not capture the increases in land value from new urban developments.

African cities need debt

Even if African cities were to become more financially self-reliant, they would likely still remain underfunded compared to the West. These cities are stuck in a low-growth trap. There is a limit to how much revenue they can expect from their mostly low-income residents, and they can’t invest in programs to boost productivity without growing their revenue. Another way of phrasing this is that the amount cities need to spend on a given resident is more than the revenue that resident provides to the city.

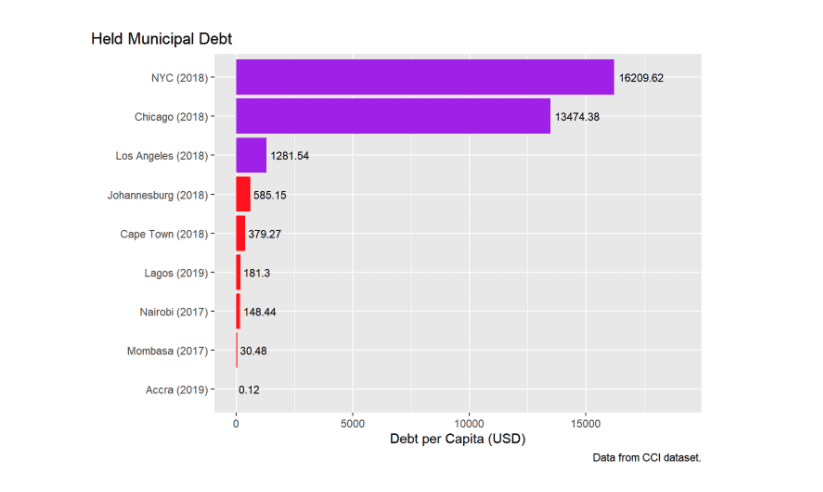

This trap is precisely what public debt is meant to address. If policymakers believe that a program can boost future productivity and economic growth, then they should take on debt to finance that program. If successful, the benefits of that program will more than pay for the initial costs. In the West, cities achieve this by issuing municipal bonds. In Africa, however, credit is difficult to acquire. Our data shows that the selected African cities hold $220.79 in total debt per capita, while the top three US cities hold $10,321.85 per capita. Certainly, African cities struggle to acquire debt due to economic fundamentals. These cities are inherently risky and investors may be unwilling to lend them money. However, the problem is further exacerbated by a weak institutional environment and combative politics. Jeremy Gorelick argues that in many countries, national governments are unwilling to let their cities make independent borrowing decisions. This is true even if investors are willing to lend to these cities. To date, only a small number of sub-Saharan cities have successfully borrowed money. These come from countries with more advanced fiscal decentralization, such as South Africa, or cities that have been granted special provincial powers (e.g., Lagos and Nairobi).

The prevailing narrative is that African cities are largely underfunded by institutional design. Central governments are hesitant to give cities the fiscal autonomy needed to run more effective budgets, either because they want to keep those resources for themselves or they fear large metropolises will form rival power bases. This is the case in revenue-generation, in which local governments are not given access to lucrative sources of income, and in borrowing, in which laws or political norms may forbid cities from taking on debt.

Data Sources

Paulais, Thierry (2012). Financing Africa’s Cities: The Imperative of Local Investment. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/12480

Tax Policy Center (2020). “Some Background: What is the breakdown of revenues among federal, state, and local governments?” In Briefing Book. Washington, DC: Tax Policy Center. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-breakdown-revenues-among-federal-state-and-local-governments.