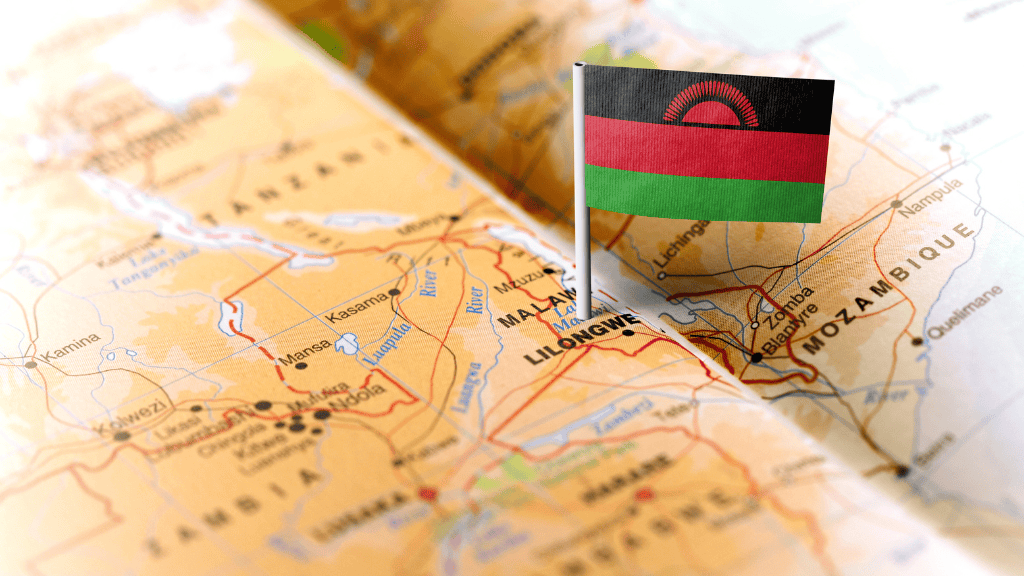

Jon Vandenheuvel is obsessed. He is obsessed with affordability, auditability, and bankability. According to Jon, these three things are the keys to lifting developing economies out of poverty. Currently, he is focused on providing housing options to Africans with incomes between $50 and $250 a month. At the present time, Jon’s work is all happening in the southern African country of Malawi. Malawi is a long thin country that hugs the west coast of Lake Malawi, one of Africa’s Great Lakes. Only 3.6 million of Malawi’s 20 million people live in urban centers, but this proportion is increasing at a rate of over 4% a year. When paired with its overall population growth rate of ~2.6% a year, it becomes clear that urban development is a critical theme for Malawi over the next couple of decades. Malawi, of course, is just a microcosm of Africa at large. Fundamentally, what Jon is doing with his company, Small Farm Cities, is taking “a systems approach to systems problems” with urban development that focuses on scalability and replicability, and he is doing it in a way that builds wealth for his target market.

The key objective for Small Farm Cities is to move people from the informal economy to the formal economy. This is why Jon is obsessed with affordability, auditability, and bankability. It is through focusing on these three metrics that Jon can help move large numbers of people from the informal to formal. Jon looks at the housing and economic situation in Africa in terms of concentric circles. In the center circle, you have gated communities. He says that Africa is replete with gated communities that cater to the wealthiest Africans and expats. These communities have regular utilities (electricity, water, sewage, etc.), security, and formalized property rights. The next circle out are the major cities like Nairobi, Lusaka, and Maputo. The regularity of utilities, quality of security, and protection (and de facto existence) of property rights varies city by city, but overall outside of gated communities, none of those factors are as strong. The third circle is all of the other places where Africans are living. Whether in smaller cities, villages, or rural communities, utilities are poor or non-existent, security is not good, and property rights are mostly informal and poorly protected. As you move from the inside to the outside of the concentric circles, the quality of utilities, security, and property rights deteriorates. Jon is focused on this last circle of people.

So, how does focusing on the metrics of affordability, auditability, and bankability help raise the quality of utilities, security, and property rights in this outside circle? Jon believes that the metrics and the three factors are closely tied together. This belief was instilled in Jon via the arguments in Hernando de Soto’s book The Mystery of Capital. In this book, de Soto argues that outside of the West, many people don’t have access to credit because the property that they claim is secured informally and therefore cannot be used as collateral to acquire credit. So, if more Africans have property that is affordable they can acquire it. If this property can be audited, then its value and ownership can be verified by third parties. If you have a property that has been or can be audited, then it can be used as collateral, which means that the owner is bankable and can be extended credit. Fundamentally, this is the process of moving from informal to formal economies, and once a person is bankable, their economic opportunities increase dramatically as they can obtain credit to do things like start a business. Small Farm Cities aims to catalyze this cycle by addressing each of the metrics. It starts with the issue of affordability.

Affordability is contextual. What is affordable to the average American or European is not affordable to the average African. Currently, the international poverty line is an income of $2.15 per day, which is $64 a month. As mentioned above, Small Farm Cities’ target market is Malawians making between $50 and $250 per month. This target market then straddles the international poverty line. The broad guideline for how much one should spend on housing per month is no more than 30% of your gross monthly income. So, in the case of a Malawian making $50 a month, affordable housing would cost no more than $15-$20 per month, and for a Malawian making $250 a month, they should spend no more than about $75 per month on their housing. Broadly speaking, Small Farm Cities aims to provide an integrated platform for residents that gets them onto the informal-to-formal conveyor belt.

Small Farm Cities has already begun building this integrated platform. By building fully integrated “live, work, play” urban developments on a charter city model, he believes that he will be able to efficiently move people from the informal to formal sectors of the economy. The general model of a small farm city has three elements: a private company with a real estate development, a farmer “cooperative,” and a commercial center. First and foremost, Small Farm Cities is a private company, and it is building private projects. Ideally, this city is a charter city under the laws of the relevant host country. Under Malawi’s new special economic zone law, SEZs – and the business-friendly rules they allow – can be applied to entire urban areas and secondary cities¹. These projects are done on a subdivision model where plots are sold to residents. Small Farm Cities (the business) provide residents with all the benefits of a formal economy – with clear property rights, digitized records and social services, and universal access to water, electricity, and sanitation.

Second, the farmer cooperative is a business that is privately owned but provides residents with professionally managed production, marketing, and sales assistance.

Third, each small farm city will have a commercial center. This commercial center will have a range of activities from industrial activities such as agricultural processing and light manufacturing; commercial activities such as professional services, retail enterprises, sports, recreation, and cultural enterprises; education and health enterprises; and also the corporate municipal center that will handle activities such as the postal service, utilities, and maintenance.

Small farm cities as a model were designed to be replicable and scalable. In a very Silicon Valley way, the first Small Farm Cities project started with a prototype, moved on to a minimum viable product (MVP), and is now working on its first scaled-up project. The prototype was the Njewa Tech Center, a project that was built for just $100,000 and housed 10 people. The next step along the scalability path was the Mpingu Gardens development, built for $350,000 and able to house over 100 people. Now, Small Farm Cities is building its next phase, the Titanium Gateway project. This project has a budget of $1 million and will house at least 1,000 people, though it is highly likely that the project will be scaled to house thousands more. This is notable in part because, for just 10 times the cost of the prototype, a Small Farm Cities project can accommodate over 100 times the number of people. Pronomos Capital is a venture capital firm that is “using the lessons of Silicon Valley to create a new model for urban development where the city is the product.” The Small Farm Cities’ approach to developing new cities was exactly what they were looking for, and has been an investor from the prototype stage.

While there currently isn’t anything larger planned (at least nothing that has been disclosed to me), it is easy to imagine a next phase that aims to house tens of thousands or more. This model is also replicable. Whether in the size of Titanium Gateway or a larger entity, while the specifics of the model are tailored to Malawi’s circumstances, there is nothing about the framework of the model that is Malawi-specific. This means that the model could be used across Africa, or even in other regions of the globe.

Looking forward, Jon is not just focused on the build-out of the Titanium Gateway project, but he is already starting to think bigger. He is interested in taking an integrated approach to developing a larger corridor area in Malawi in conjunction with other major businesses working in the country. This development corridor would stretch from the town of Chipoka on the shores of Lake Malawi to the capital of Lilongwe. However, in order to take maximum advantage of not just the development potential of this corridor in particular, but the small farm cities model in general, Jon wants to start giving out mortgages. Currently, there are only about 1,000 mortgages in the entire country of Malawi, with over 20 million people. Jon wants to raise capital to create a fund that will provide mortgages for his target markets so that they can get onto the informal-to-formal conveyor belt.

Overall–in this author’s opinion–the small farm cities model is one of the best in terms of being well thought out, actionable, replicable, and scalable. Jon built out his theories and eventually the small farm cities model after years of working on commercial agribusiness and special economic zone projects in Africa, he even wrote a book, Africa Risk Dashboard, about it. This model, scaling from prototype through to MVP and on to a replicable and scalable product – fully embodies the key value proposition of charter cities. By concentrating needed reforms in a small, geographically clustered area, pinpointing what works and what doesn’t on this small scale, then scaling up the successful reforms more broadly, Small Farm Cities follow in the illustrious history of free cities and special economic zones of the past. From the city-states of Ancient Greece and later of Renaissance Italy, to the independent cities of early modern Europe, to the freeports and trade hubs established across the globe during the Age of Discovery, to the SEZs that brought in more market-oriented policies to China under Deng Xiaoping post-1978 – this Minimum Viable City model has a proven track record of economic transformation; of transitioning not just cities but entire countries and regions from informal to formal. Jon’s obsession is rightly placed.

¹ CCI helped provide legal advisory services to help draft this new SEZ law. You can read more about the SEZ law via Jeff Mason’s X thread.