Key takeaway: Charter cities can instigate administrative, regulatory, and institutional reforms that not only enable economic development but also help improve processes for long-term planning and adaptive decision-making.

— — — —

A capable, flexible, and well-informed governance system is perhaps the most crucial component of resilience. Governing institutions implement policies and practices that either bolster or undermine the ability of urban environments to absorb climate shocks and adapt to changing environmental conditions. It is also an underappreciated fact that a good business environment is a central component of a resilient urban system.

A productive urban economy allows for inward and upward expansion, rather than outward sprawl. It also enables effective mobilization of infrastructure investment, better public services, higher levels of innovation, and greater cooperation. In fact, “economic and physical evolution go hand in hand…[so] cities need integrated legal and regulatory frameworks that will enable both economic and spatial development.”

Charter cities can help usher in the administrative and regulatory environments necessary for resilient development, particularly regarding economic governance. By allowing for innovative institutional arrangements, charter cities can also experiment with building urban governance systems that are more capable of balancing high-level vision with changing local conditions.

The scourge of weak governance

Governing a city is no easy task. The density, diversity, and dynamism of the city places unique demands on institutions. These pressures tend to be even greater in cities across the Global South, which are simultaneously facing growing climate stressors and rapid growth. The eminence of these challenges requires governments equipped with the capacity to monitor and anticipate climatic changes, migration, population growth, and urban expansion. The ability to coordinate and implement policy responses in the wake of disasters or other external shocks is also vital.

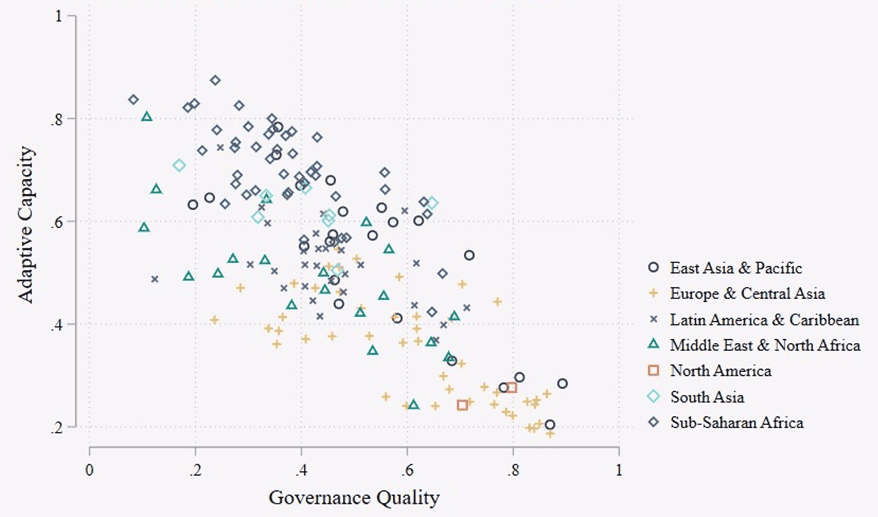

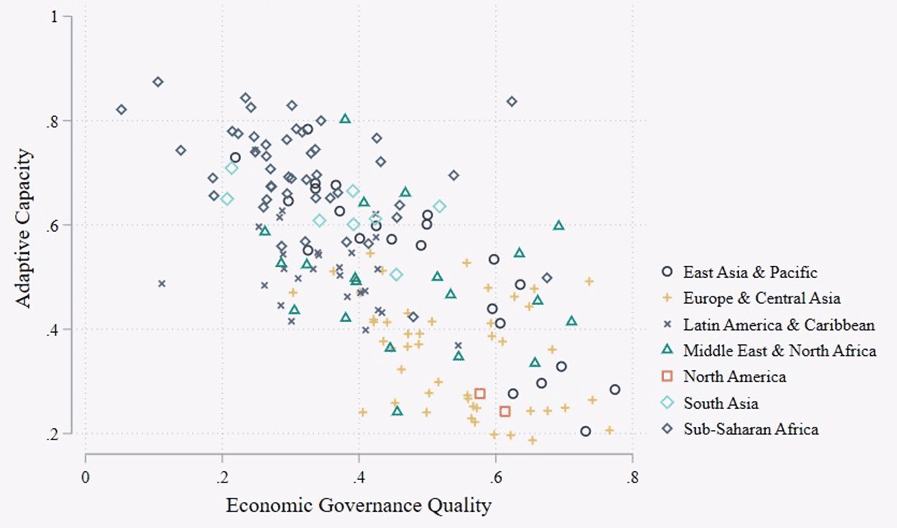

Generally, cities in the Global South face higher levels of exposure to climate change and have lower levels of adaptive capacity, largely due to persistently weak governance. In fact, there is a clear negative correlation between adaptive capacity and both quality of overall governance and economic governance (see Figures 1 and 2). ¹ Figures 1 and 2 show that countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, in particular, tend to have lower governance scores than countries located in Europe, Central Asia, and North America.

Source: Author’s calculations using data from ND-GAIN (2023).

Governments across the Global South often lack the financing, stability, and established administrative procedures necessary to maintain a high standard of governance and an attractive business environment. Given the gravity of the challenges coming to bear on cities in the Global South, there is a clear need to replace “traditional institutional and social structures with modern ones centered in a formal legal apparatus, and massive local and intercity infrastructure investments…all in a short span of time.”

However, the persistence of weak governance in many developing countries endures despite (or, in some cases due to) countless efforts at institutional reform. Such countries are caught in what some scholars call a “state capability trap” wherein the capacity of the state to implement policies is severely constrained and improving very slowly.

This stagnation is often attributed to the tendency for new governing institutions to undermine emergent forms of organization and disincentivize innovation. The result is a prioritization of form over functional effectiveness. Moreover, entrenched elites often benefit from maintaining the status quo, perpetuating ineffective systems that serve their interests at the expense of broader societal advancement.

“New cities with new rules”

By establishing pockets of effectiveness where good governance is substantively implemented, charter cities can provide the necessary institutional structure for sustainable urban development. Empowering cities with significant decision-making authority enables the swift establishment of capable administrations, which can uphold the rule of law and provide essential public goods. Devolving power to the city level reduces information barriers between policymakers and on-the-ground realities. This is particularly important for effective disaster preparedness, during extreme weather episodes, or in the aftermath of disaster.

When compared to the national level, cities – especially new cities – offer a relatively “small entry point for effective development.” As such, charter cities can help “avoid the public choice problems that often stymie reforms in existing jurisdictions without radically changing the rents enjoyed by elites…[allowing] for deeper institutional change than would otherwise be politically feasible.” Policies and strategies which are successful at the charter city level can then be scaled to the regional or national level, instigating widespread reform based on proven strategies tailored to the local context.

For instance, granting charter city authorities control over land administration holds promise for significant improvements in land governance. By maintaining accurate cadaster records, streamlining land use planning, and establishing ‘one-stop-shops’ for land titling, charter cities can help address long-standing issues of inefficiency, complexity, and corruption in land governance. This not only enables the construction of more productive, resilient cities, but it can also help jumpstart gradual processes of widespread improvements to land administration, generating positive environmental, economic, and social effects.²

Crucially, another key strength of charter cities lies in their flexibility to adopt institutional forms and policies that enhance performance and resonate with local political legitimacy and cultural norms. Rather than adhering to standardized institutional models, charter cities provide fertile ground for experimentation.

For example, charter city developers may choose to pursue a private-public partnership (PPP) governance model, whereby the developer works with the sovereign authority to set up a special jurisdiction and maintains some influence in governance decisions. Under such an arrangement, city managers are incentivized to provide good governance because they stand to benefit from rising land values.

One of the most comprehensive PPP arrangements for city governance was pioneered in Gu’an, China by the China Fortune Land Development Co. (CFLD). Under contract with the local government, CFLD took on responsibility for city planning, infrastructure development, service provision, administration, and industry solicitation. This model has proven remarkably successful, with Gu’an becoming the wealthiest county in its province.

This approach to urban development can also give rise to quasi-market conditions where there is competition between various charter city jurisdictions – or even neighborhoods within a single charter city – to attract residents through high quality of governance and service provision. Not only does this encourage city developers to plan for long-run growth – including consideration of climate risk – but it also creates space for innovative policy interventions.

However, charter city authorities must be keenly aware of the limitations of various PPP arrangements. For one, failure to democratically include residents in governance decisions can lead to poor outcomes and lack of accountability. There is also a risk of creating expensive, profit-driven enclaves that perpetuate social exclusion. In charting the course for resilient and prosperous urban futures, charter cities must strike a delicate balance between innovation and accountability, between private sector efficiency and public sector responsibility, and between economic growth and social equity.

Let a thousand urban experiments bloom

Ultimately, the administrative, regulatory, and institutional reforms pioneered in charter cities can have direct implications for resilience. For one, charter cities can create a clear system of overarching rules that support a strong business environment, establish clear administrative procedures, incentivize adaptive policymaking, and enable institutional flexibility. Crucially, this system of rules can be substantively different from the host nation, allowing for the emergence of urban pockets of effectiveness that generate significant economic returns for the national entity.

Moreover, charter cities can create space for continued iteration and improvement of policy interventions, service provision, and institutional arrangements. Such experimentation can also benefit the host country, providing incubation grounds for initiatives that may be scaled to the national level. In this way, charter cities can not only help overcome institutional constraints to economic growth, but they can also push the boundaries on how governing bodies are arranged and operate.

These new approaches are critical for understanding how institutions can more effectively adapt to changing external circumstances. As we navigate the challenges of climate change and rapid urbanization – especially in the Global South – charter cities offer a promising avenue for reimagining how cities are governed and how they can contribute to the long-term flourishing of mankind. Indeed, human prosperity is, in many ways, intricately bound to the evolution of the city. It is time to embrace the potential of charter cities and let a thousand new urban experiments bloom.

¹ ND-GAIN uses the World Bank’s Doing Business (DB) indicators to measure economic governance. DB was discontinued in 2020 due to data tampering for Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia, China, and the United Arab Emirates – evidence of doing shady business. These issues affect ND-GAIN’s economic governance measure. The general governance measure pulls from the World Governance Indicators and includes (i) political stability and nonviolence; (ii) control of corruption; (iii) regulatory quality; and (iv) rule of law. The “adaptive capacity” indicator includes 12 measures: agriculture capacity (fertilizer, irrigation, pesticide, tractor use); child malnutrition; access to reliable drinking water; dam capacity; medical staffs (physicians, nurses, and midwives); access to improved sanitation facilities; protected biomes; engagement in international environment conventions; quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure; paved roads; electricity access; and disaster preparedness.

² Of course, land acquisition, registration, and titling for a charter city can also be undermined by a failure to appreciate the social and cultural dimensions of land. The experience of Rajarhat New Town (discussed in Box 2) provides clear evidence of this fact. Despite the failure being on a much smaller scale, this does not remedy the injustice of the inequitable state-led land acquisition process that many famers were forced to endure, which also undermined the city’s expansion. Ultimately, land issues have far-reaching implications, which are difficult to disentangle at both large and small scales. Charter cities offer one way to gradually implement land-related reforms.