Key takeaway: Directing urban growth away from climate-vulnerable zones and pre-emptive urban expansion in in-migration hotspots can help decrease exposure to changing environmental conditions and extreme weather events.

— — — —

In a survey of global cities, one feature stands out: coastal or riverine location. The primary reason for this is well-understood. Cities have historically proliferated along waterways due to trade route accessibility, which subsequently fosters economic growth and development. However, this geographical advantage also comes with inherent risks.

Costal and riparian cities face heightened vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, including rising sea levels, storm surges, and flooding. As these environmental challenges grow, urban expansion in hazardous zones poses an increasing threat to residents, especially in haphazardly built and poorly-provisioned neighborhoods.

Charter cities offer a unique opportunity to direct urban growth and expansion away from these high-risk zones. By strategically locating new urban centers in safer areas, charter cities can help decrease the likelihood of exposure to climate-related hazards, safeguarding communities against environmental changes and extreme weather events. Crucially, satellite charter cities can also alleviate pressure from mega-cities in in-demand regions to help leverage climate-induced migration into productive urbanization.

A growing city-climate conundrum

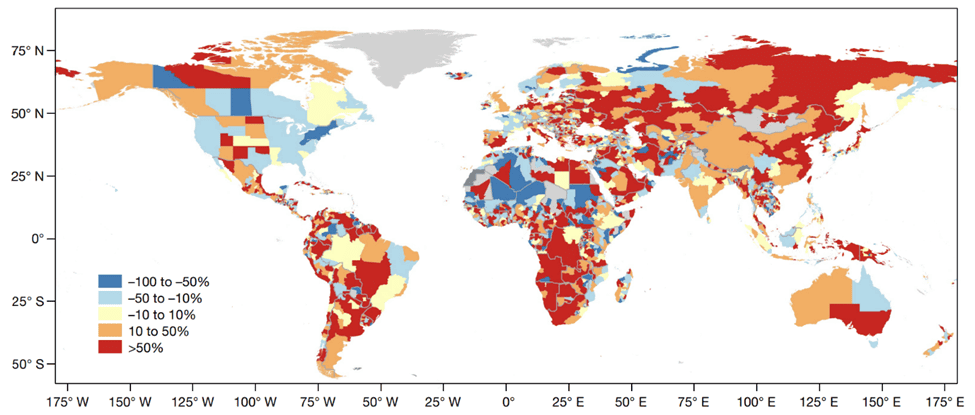

Cities are rapidly expanding into areas that are highly susceptible to climate-related risks, according to findings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). A recent study underscores this trend, finding that urban centers are expanding most rapidly in flood-prone regions. The authors note an increase in the percentage of urban built area located in zones with medium or high flood hazard. In fact, expansion in highest flood-hazard zones outstrips the average pace of global urban expansion – 121.6% compared to 85.4% (see figure below). Alarmingly, “flood-exposed growth has been especially rapid in middle-income countries…and low-income countries may risk following this trajectory in the future.”

Source: Rentschler et al., 2023. “In red areas, the share of flood-exposed settlements in increasing, that is, settlements in high-hazard flood zones have expanded at least 50% more than settlements in flood-safe areas. In blue areas, flood exposure is decreasing.”

As climate change continues to “reshape the comparative advantage of regions,” migration to cities is also expected to surge, driven by the declining viability of many rural livelihoods, particularly agriculture. In search of alternative employment opportunities, households may choose to “abandon farming or other rural livelihoods altogether, as has happened in rapidly urbanizing countries such as China.”

This presents a significant conundrum: cities are located in areas that are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, yet they are expected to act as a crucial lifeline for millions engaging in occupational and spatial climate adaptation. It is crucial that policymakers facilitate planned and orderly migration to “supportive environments” offering “low risk and high opportunity.” In other words, policy must support the growth of productive, climate-safe cities.

Charter cities and climate-safe urbanization

The IPCC lays out a spectrum of strategies to reduce the risks faced by coastal cities and settlements, ranging from bolstering protective infrastructure to relocating communities to less climate-vulnerable areas ¹. Although many cities have started to engage in retrofitting and the construction of climate-resilient infrastructure, establishing new cities in less climate-exposed locations is a comparatively under-explored adaptation strategy.

Relocation of human settlements – or “retreat” as it called by the IPCC –holds immense potential as an adaptation strategy. This approach can not only direct households towards areas less prone to flooding, but it can also expand the location options available to households who currently face the difficult choice of risking safety for economic opportunity.

Providing urban alternatives can be particularly impactful in countries with unbalanced urban growth, which often occurs when one mega-city dominates all others due to underinvestment in secondary and tertiary cities. This “under-provision” of cities is particularly frequent in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, some countries, such as Kenya and Malawi, have already started to implement initiatives to promote secondary city development.

Establishing satellite charter cities – new cities located near but separate from large metropolitan areas – can also help alleviate urbanization pressures on rapidly growing cities in climate-induced migration hotspots. The preemptive construction of satellite cities in less-hazardous regions can also help decrease exposure to extreme events. This approach can help facilitate “well-managed, ‘in-migration’ [and] create positive momentum…in urban areas which can benefit from agglomeration and economies of scale.”

The strategic establishment of new cities presents an opportunity to avert large-scale reactive relocation in the future, which would likely cause significant social and economic strife. By proactively building cities in areas which enjoy fewer climate risks, yet are still well-integrated into global supply chains, it may be possible to foster the early growth of tomorrow’s climate-safe cities.

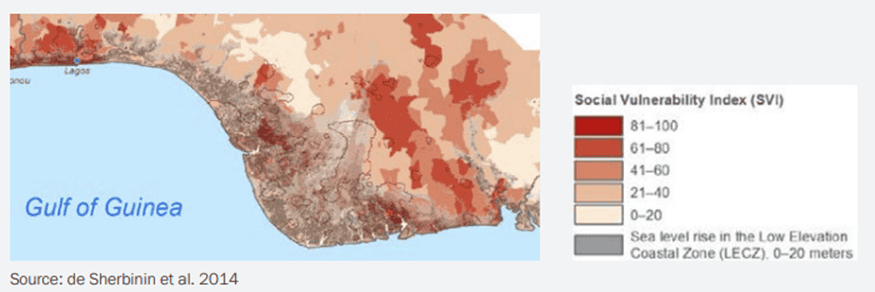

Nigeria offers one example of a country that has attempted to attract citizens to a new, less climate-vulnerable city – Abuja. Although the impetus for the project was to balance Nigeria’s urban growth through the development of a new capital city, Abuja’s central location and lower flood susceptibility offer an attractive alternative to flood-prone Lagos.

Since the government relocation in 1991, the city has grown quickly, swiftly ascending to Nigeria’s fourth most populous city, hosting nearly 4 million residents. In fact, research shows that Lagos is “expected to experience a notable decline in net climate migration,” with the emergence of Abuja as capital city prompting increased migration to the “north-central zone.”

Source: Rigaud et al., 2021.

However, the new city of Abuja has not been without its share of challenges. The city’s design and construction have cost billions of dollars, yet still the implementation of the original master plan is incomplete, leading to urban sprawl and flood vulnerability. Government relocation nearly did not happen due to political opposition. The cost of living also remains comparatively high and out of reach for many Nigerians.

Nonetheless, the city and its sub-nodes are still some of the fastest-growing urban areas on the planet – evidence of demand for productive cities in less climate-vulnerable regions. Strategically placed new cities such as Abuja have immense potential to help drive productive urbanization and generate significant economic opportunities in areas less prone to climate risks. This not only helps households engage in safer occupational and spatial adaptation, but it also protects the long-run growth of urban centers.

Towards strategic urban relocation

Overall, there is a compelling case to be made that there is a marked under-provision of cities in climate-safe locations, particularly across the Global South. This not only constrains the migration options available to households being impacted by climate change, but it also directs them toward hazardous locations. By taking proactive steps to establish new cities in safer locations, the exposure of urban populations to climate hazards may be reduced, while creating more economic opportunities for households.

Although “increased attention is being given to pre-emptive resettlement and the potential pathways and necessary governance, finance and institutional arrangements to support this strategy,” even more attention is merited. It is imperative that policymakers, urban planners, and communities collaborate to navigate the complexities of climate change and develop innovative approaches to harness the full potential of new city construction ².

Doing so can serve as a pivotal tool for climate adaptation and sustainable development amid an uncertain future. Through collective action and foresight, we can navigate the challenges posed by climate change and pave the way for resilient, thriving urban environments.

¹ The six strategies suggested are: “(i) vulnerability reducing measures, (ii) avoidance (i.e., disincentivizing developments in high-risk areas), (iii) hard and soft protection, (iv) accommodation, (v) advance (i.e., building up and out to sea) and (vi) retreat (i.e., landward movement of people and development.”

² Devolved governing authority and charter cities may provide such a viable institutional arrangement (see forthcoming blog and Section 2.c. in forthcoming white paper).