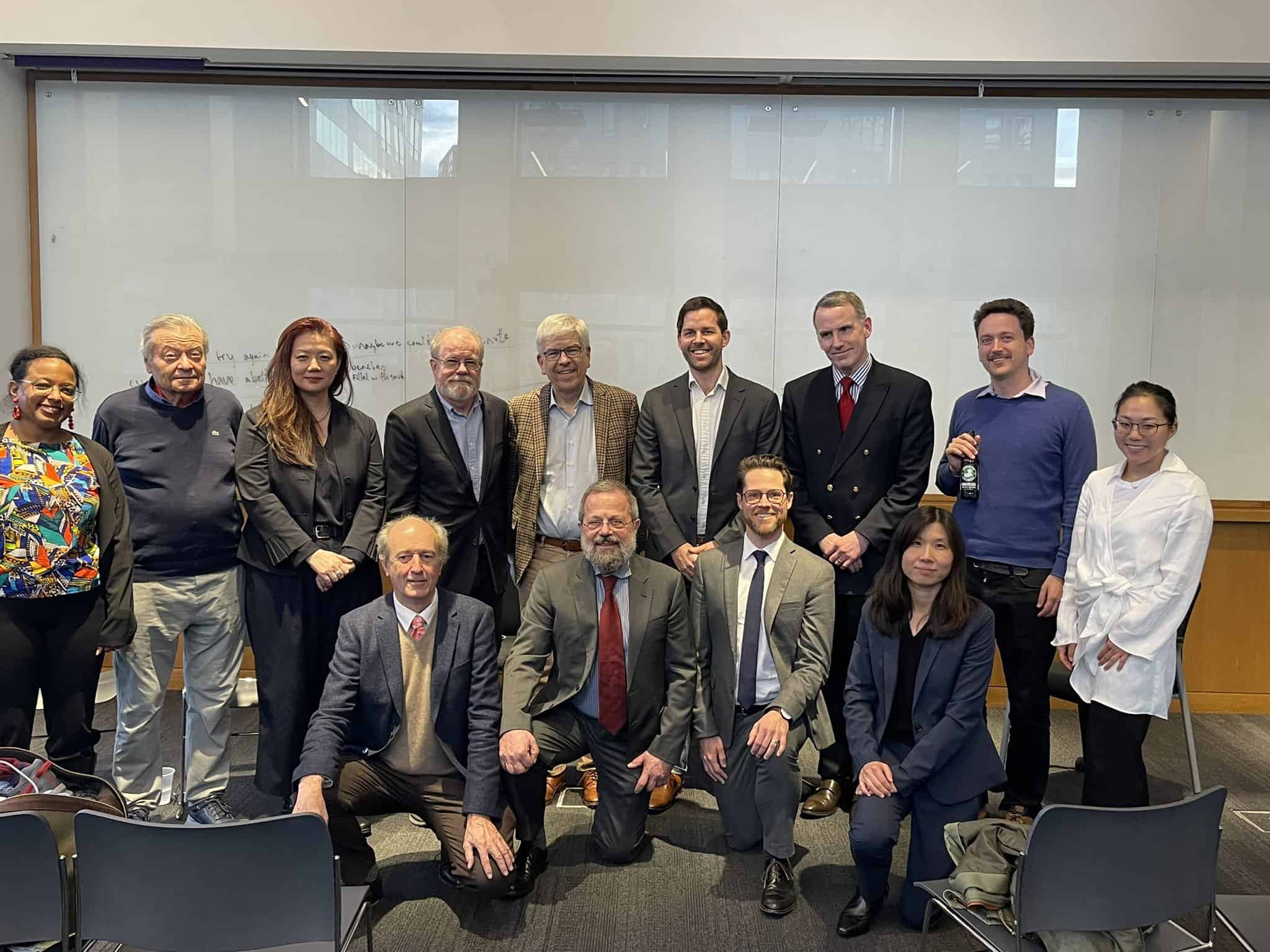

On March 11th, the Charter Cities Institute (CCI) and the Marron Institute of Urban Management co-hosted the NYU New Cities Conference in New York City. The event brought together economists, political scientists, architects, and urbanists to discuss the challenges of and solutions to Africa’s rapid urbanization. Africa will see over a billion new residents move into its cities by 2050 – the equivalent of 100 megacities – and without innovative solutions, its cities will struggle to translate population growth into economic prosperity. Concerned with growing pressures on already overburdened infrastructure and public services, many policymakers are turning to an ambitious idea: rapid urban expansion and the construction of new master planned cities from scratch. The conference aimed to discuss how new cities, charter cities, and urban expansion will impact Africa’s urban future.

Dr. Paul Romer, the founding Director of the Marron Institute and co-recipient of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, delivered the keynote opening talk. Romer first introduced the idea of charter cities in a 2009 TED talk, where he proposed that a new city built on a greenfield site, backed by a foreign guarantor, and empowered with Western-style institutions can launch economic growth in developing countries. The concept is often simplified as “building a Hong Kong in Africa,” and his model was harshly criticized as neocolonial. At the conference, Romer reengaged with charter cities and contextualized it within contemporary international trends. He touched on urbanization, international conflict, the rule of law, and global migration. Romer readily acknowledged the controversies around new cities and charter cities, where he referenced difficult questions about balancing democratic transparency and executive authority in governance. He warned that there is a thin line between special jurisdictions that incentive reforms and so-called “concession zones” that uphold the status quo.

A main theme of Romer’s talk, and a point he returned to throughout the conference, was the importance of choice. He argued that the prevailing Westphalian system poses a trilemma: when presented with mass migration, democratic accountability, and equal treatment under the law, states can only pick two. This is because borders incentivize states to fear the destabilizing effects of immigration within a democratic system. States are therefore left to choose between disenfranchising immigrants as non-citizens, curbing the influence of immigrants by eroding democratic institutions, or limiting immigration altogether. Consequentially, those disadvantaged by history are unable to choose a better life. Romer believes that addressing the tension between migration and democracy is one of the key problems of the contemporary world, and it is a problem which charter cities can play a role.

Other advocates of charter cities included Dr. Mark Lutter, the founder of CCI, and Kurtis Lockhart, the Executive Director of CCI. While Romer’s talk remained mostly high-level, Lutter and Lockhart tried to ground charter cities in practical experience. Lutter discussed his founding of CCI and what a “sustainable model” for new cities looks like. He stated that the fundamental logic behind charter cities is that (1) good institutions matter to prosperity and (2) it is easier to build good institutions on greenfield sites. Lutter referenced Shenzhen as a “proto-charter city,” where the Chinese government allowed limited autonomy and Western institutions to boost economic growth. However, while China had the state capacity needed to make Shenzhen work, most of Africa has weak states. Lutter argued that public-private partnerships (PPPs) are a better fit for regions without robust governments. He believes that PPPs are more politically tractable and easier to implement than the foreign guarantor model initially proposed by Romer.

Lockhart shifted the presentation to discuss CCI’s ongoing activities. He made the point that while there are many organizations working to improve Africa’s existing cities, almost no one is working on improving the hundreds of new cities currently being built. CCI wants to fill that gap. Lockhart commended CCI’s research, including a novel database that tracks every modern new city since 1945. The database will launch in May. Lockhart also discussed CCI’s partnerships and the organization’s role in making new cities more inclusive to low-income residents.

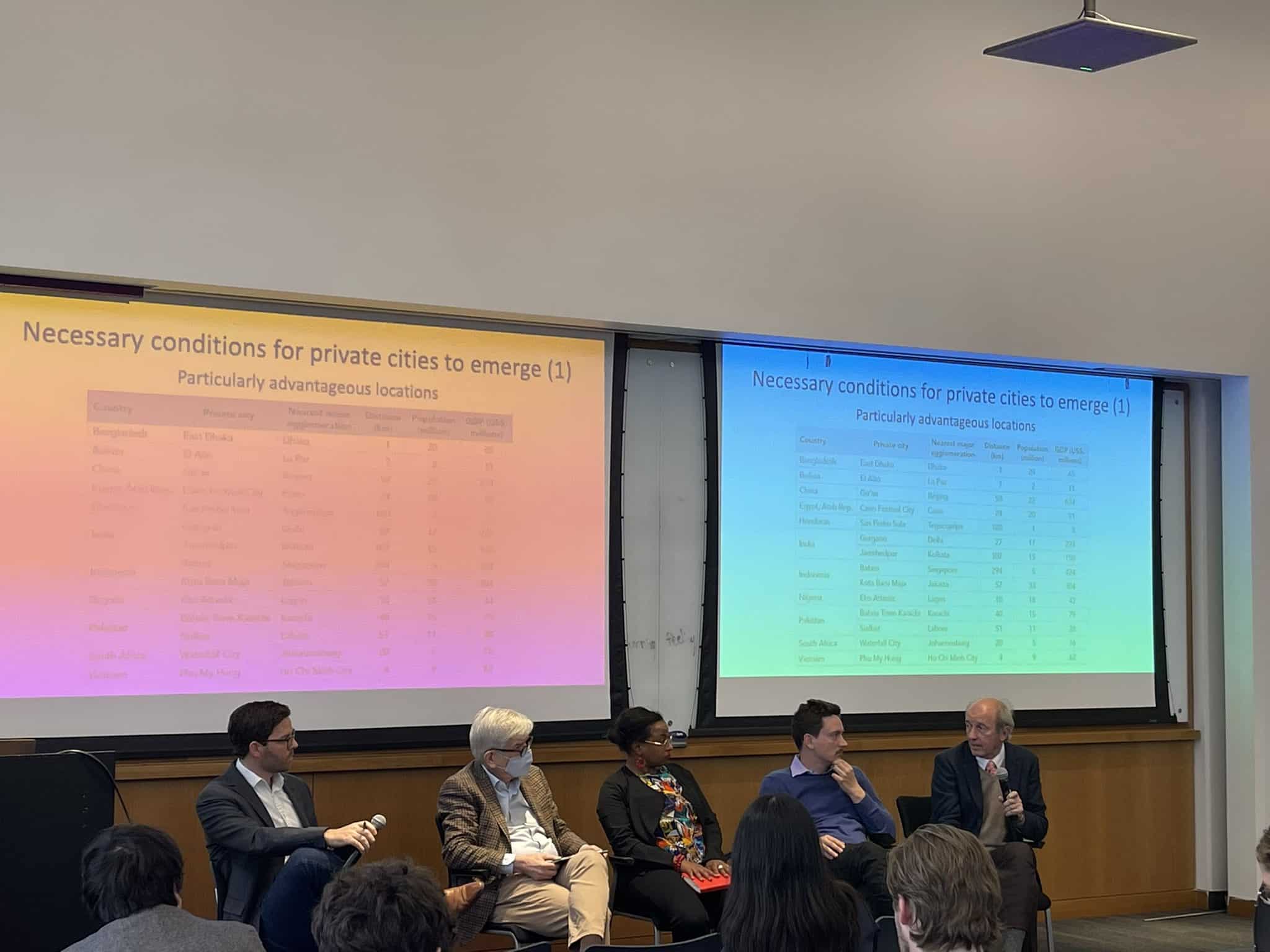

Dr. Martin Rama and Dr. Yue Li spoke next about their work on private cities. Rama is the former Chief Economist for Latin America and the Caribbean at the World Bank, and Li is a Senior Economist at the Bank. Rama emphasized that cities built and managed by non-government private actors is a reality. Most of the cities he and Li studied already have a population of nearly a million people. Rama also noted that private cities are not a contemporary anomaly. History has numerous examples of private-led cities, including medieval Paris, renaissance Florence, and modern company towns. Despite their scale, urban researchers neglect the phenomenon.

Li introduced an economic model for private cities. She explained that private cities are a reaction to weak state capacity and unmet urbanization needs in profitable areas. The model also described how the form of public-private cooperation leads to various social outcomes. Rama brought the discussion back to policy, where he explained how their analytical framework can guide decisions on PPP legal structures and private subsidies. Their research will be published in a book this month.

Astrid Haas brought a critical voice to the conference. She is an urban economist with years of professional experience working on municipal issues in Africa, and she is skeptical that new cities, private cities, and charter cities can address Africa’s urban struggles. Haas argued that because privately developed cities are driven by profit, they need to cater to a small elite class to make a return on investment. As she puts it, “not everything in a city can be packaged into a bankable project.” Haas further noted that Africa has dysfunctional land markets, so even well-intentioned projects will be exploited by elites. She kept going back to Eko Atlantic City in Nigeria, where an unbuilt 2-bedroom condo already costs US$1.5 million in a country where 61% of the population lives on US$1 a day.

Haas also argued that the problems facing Africa’s economic development are larger than cities. Even if a successful charter city were built, it would not yield the benefits its proponents claim. Africa faces large infrastructure deficits that impede economic linkages. Most Africans are farmers and are unable to access supply chains due to a lack of roads, cold storage, and efficient ports. The solutions to this are not as simple as special jurisdictions and tax breaks. Her point was that you cannot build a successful city in a hostile environment, and charter cities proponents are not paying enough attention to that environment. Instead, Haas urged us to focus on the urban expansion of existing cities. Mass internal migration is already creating new cities without the need for flashy private development projects, and a more effective approach would be to equip the small towns people are already migrating to for their inevitable expansion.

Dr. Juan Du, the Dean of the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto, also brought new perspectives to the charter cities narrative. She discussed Shenzhen’s development and the popular myths surrounding its history. Shenzhen was the first special economic zone in China, and it grew from 300,000 people to over 12 million in just 30 years. While charter cities proponents often think of Shenzhen as an example of state-led experimentation in pursuit of growth, Du explained that Shenzhen’s special designation was largely driven by local officials as a “last ditch” effort to survive; China was “dying,” and officials were motivated to try anything new. She also challenged the idea of Shenzhen as a “new city” developed from rural fishing villages. Prior to its designation as a special economic zone, Shenzhen was already home to historic urban centers with dense populations. Likewise, Shenzhen’s growth did not happen solely through top-down planning.

Du’s discussions offered two lessons to those trying to replicate China’s experience in Africa. First, we need to pay attention to local networks. Du highlighted that much of the early foreign direct investments that flowed into Shenzhen were not going to large corporations. Rather, they came from friends and families investing in small businesses. Shenzhen’s vibrancy came primarily from the informal economies of its urban villages. Du’s second advice was to look at the humanistic aspects of China’s cities. She made the point that although Hong Kong looks like an economic success, its history was driven by contentious social struggles. Intellectuals were fiercely against colonial rule, despite the purported enabling institutions imposed by the British. For that reason, Du wasn’t convinced that Hong Kong should be a model for Africa.

Dr. Patrick Lamson-Hall gave a crucial practitioner’s perspective to the conference. He is an economist at the Sahel and West Africa Club and the founder of Fitted Projects, a boutique urban design firm. He has also worked with the Marron Institute on urban expansion, where he helped cities in Ethiopia predict and plan for rapid population growth. He pointed out that three quarters of urban migrants are moving into new areas of existing cities, especially smaller cities. Many “new cities” are piggybacking on this trend by developing land on the fringes of existing cities. The problem however, is that the vast majority of the places people are moving to have no public or private sector plans. This will lead to informal settlements and unproductive markets.

Lamson-Hall’s discussed his work addressing this problem. The Marron Institute invested US$500,000 to train officials in four Ethiopian cities in the principles and practice of urban planning. The program returned US$10 million in public investments and US$77 million in private investments. Lamson-Hall ended by proposing improvements to current African planning. He believes that urban planners should plan on a more granular level using smaller plot sizes. This runs counter to the prevailing practice of packaging land as large blocks, which are only affordable to large private developers. The benefits of “small plot planning” is that it gives development power to a greater range of stakeholders, which is more flexible to changing urban needs and inclusive of low-income residents.

Alain Bertaud contributed another practitioner’s perspective, drawn from his experience as a principal urban planner at the World Bank. He reflected on a few ongoing new cities projects and questioned what problems they were trying to solve. He argued that many new cities developers are not seriously thinking about why people move to cities. Cities are primarily labor markets and people move there to work. Bertaud argued that new cities must be attractive to a diverse workforce if they want to succeed. For instance, cities that cater only to the wealthy will not have sufficient people to staff service jobs.

Dr. Edward Glaeser delivered the closing remarks of the conference. He is the Chairman of the Department of Economics at Harvard University and the Director for the International Growth Centre’s Cities Research Programme. His presentation focused on how cities have adapted to the pandemic and what urban living might look like in the near future. One of his main arguments was that geography still matters, even in an economy increasingly embracing remote work. He made that case that cities do a tremendous job encouraging upward mobility and improving productivity through urban interactions. However, urban policies in the US make it increasingly difficult to build affordable housing for those who want to move to cities.

The big ideas discussed at the conference made it clear that Africa’s cities will need innovative solutions to succeed. While it is difficult to draw a common theme among a diverse set of perspectives, there was a consensus that policy solutions should be anchored by local involvement and experimentation. Du’s description of Shenzhen’s beginnings as an ambitious local-led experiment aligned both with Lutter’s vision for charter cities and Haas and Lamson-Hall’s model for urban expansion. However, there was disagreement on who should lead novel policy experiments, how we should manage its fallout, and whether new cities are the best tool to implement them.

You can find recordings of the conference on the Charter Cities Institute’s Youtube channel.