Listen:

Key Points From This Episode:

- The definition of a small farm city and details about the first community he built.

- Affordable formal ownership of housing and why it is significant for African countries.

- Providing an affordable housing baseline while incorporating building options.

- Learn about the company’s approach to housing modularity and scaling.

- Jon shares his approach to sourcing and developing talent for Small Farm Cities.

- Scaling the company’s method and how it is entering the light industrial sector.

- Unlocking Africa’s industrial potential to build communities and cities.

- Malawi’s Special Economic Zone Law and why it is a win for the country.

- Valuable lessons and takeaways from their project in Ghana.

- Transitioning refugee cities into investable and productive cities.

- His professional background and career journey to Small Farm Cities.

Quotes:

“Affordability, it almost becomes cliche, but it really has to be defined in order to be useful in terms of either designing a business or designing a policy.” — Jon Vandenheuvel [0:03:39]

“One of the things that is stunting development, broadly speaking in Africa, is that I’m not sure that developmental planners, and policymakers, and donors, and the whole financing universe has wrapped their arms around what is actually affordable.” — Jon Vandenheuvel [0:04:42]

“Economies of scale is an economic principle or law. It’s like gravity.” — Jon Vandenheuvel [0:13:17]

“I wouldn’t say there’s any secret sauce to [the work]. It’s just a lot of passion, a lot of intentionality, and a lot of respect, just peer-to-peer respect.” — Jon Vandenheuvel [0:20:51]

“You can build industries without building cities. We have this all over Africa.” — Jon Vandenheuvel [0:26:36]

“Economic freedom, opportunity, and entrepreneurship is sort of the only way to really sustainably beat poverty. But too few people have the tools to make that happen.” — Jon Vandenheuvel [0:45:06]

Links Mentioned in Today’s Episode:

MIT School of Architecture and Urban Planning

Foundation for a Smoke-Free World

Charter Cities Institute on Facebook

Transcript

[INTRO]

Kurtis Lockhart: Welcome to the Charter Cities Podcast. I’m Kurtis Lockhart. On each episode, we invite a leading expert to discuss key trends in global development in the world of cities, including the role of charter cities and innovative governance will play in humanity’s new urban age. For more information, please follow us on social media, or visit chartercitiesinstitute.org.

[INTERVIEW]

Jeffrey Mason: I’m Jeffrey Mason, head of research at the Charter Cities Institute. Joining me on the podcast today is Jon Vandenheuvel, the founder and CEO of Small Farm Cities Africa, and a senior adviser to the Charter Cities Institute. We talk about the hyper-affordable agribusiness community, Jon’s company has built-in Malawi, their next agro-industrial community that they’re also going to build in Malawi, the importance of systems solutions to systems problems like poverty, and how Jon came to be building new cities in Africa. I hope you enjoy today’s episode.

Jeffrey Mason: Hi, Jon, good to see you. Thanks for coming on the podcast.

Jon Vandenheuvel: Hey, thanks for having me.

Jeffrey Mason: So to start off, tell us, what is a small farm city?

Jon Vandenheuvel: Well, small farm city is the way to organize agriculture, and housing, and infrastructure in a coordinated way. Our company, it’s a for-profit company, Small Farm Cities. What we’re doing is we are essentially organising agricultural production, affordable housing. Then, integrating infrastructure, and both hard infrastructure, things like electricity, and water, and then, soft infrastructure systems, human resources, financial services, what we call soft infrastructure.

Jeffrey Mason: Tell us a little bit about the first community that you’ve built, where it is, what you’re producing there, how many people.

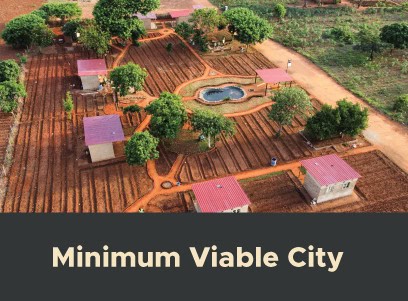

Jon Vandenheuvel: Sure, yes. We’re about 20 kilometres west of Lilongwe in Malawi, in Southern Africa. What we’ve organized there is greenhouse horticulture with a housing model. We’ve designed it for about 100 people, and we’ve set up a mortgage program for the homes. We have been in production for now a year on the greenhouse. We have about 75 employees, full-time employees. Probably 60 of them work in the agriculture space, and then the other 15 or 20 or so work either in skilled trades or management. So on the skilled trade side, we employ welders, plumbers, and carpenters on the construction side. And then, managerial talent handling everything from agronomy to human resources. Then the aquaculture as well. We do fish farming, and we also do poultry.

That’s our first project, really just a scale prototype. We have about 70-something employees and about 100 residents of the community. That’s been our first operating project in Malawi, and we started that about a year ago.

Jeffrey Mason: Okay. Now, one of the things that you mentioned, that you’re offering mortgages to people. Obviously, housing, formal housing is a big issue in Africa, where you’re doing your work. I know this is something you’re passionate about, in terms of actually giving people the ability to enter the formal ownership of housing at a price point they can actually afford. Just talk a little bit about what you’re doing there.

Jon Vandenheuvel: Sure. I guess taking a half a step back, affordability, it almost becomes cliche, but it really has to be defined in order to be useful in terms of either designing a business or designing a policy. In the case of Malawi, specifically, and Africa more generally, the minimum full-time working wage is about $50 a month. Many people struggle even to make $50 a month, because of the inconsistency of employment. Or in the case of agriculture, the seasonality of agriculture, especially agriculture that’s dependent on seasons. The devil is in the details when it comes to affordability, I mean, how much life can you afford on $50 a month? You can just reverse engineer $50, and look at 30 days, and say, “Well, if you spend $1 a day on feeding yourself and your family, what’s left?”

One of the things that is stunting development, broadly speaking in Africa, is that I’m not sure that developmental planners, and policymakers, and donors, and the whole financing universe has wrapped their arms around what is actually affordable. There’s a lot of opinions, let’s say, on, well, a house has to have this, a house has to have that. Well, once you have this, and once you have that, then the house isn’t affordable. It really becomes a matter of coordinating. When you start with the end in mind, where you say, “Well, what can someone afford if they’re making $50 a month as a family?” You can basically afford maybe $10 a month on housing, maybe 15. You sort of start from there.

What we’ve tried to do with our work is establish a baseline that’s a credible baseline. It’s not fake, it’s not made up. It’s not propped up with some external funding source, or donations, or anything. It’s like, no, strictly speaking, what can a family afford if they make $50 a month? That is really a home about $1,000 maximum. The reason for that is because, there’s really no methodical home financing, no mortgage financing. This is the real pickle when you’re essentially looking at an informal economy, and you’ve got masses of humanity, living in an informal economy, and you’re really left with a full-scale, unbankable scenario. At which point attempts to intervene, are stunted in terms of their effectiveness, because they’re not established on actual economic reality.

Our point with Small Farm Cities is that we don’t really want to bother with why mobilize investment, why even be there to sort of prop up, or perpetuate a fake economy? As I’m kind of framing our home mortgage program, our home mortgage program is built on reality. Which is what are the minimum wages, and then, what can someone afford at that minimum wage? That engineering, that financial engineering, that financial structuring, this then opens the doors. The basic economics is that, a $1,000 mortgage is about $25 a month for 48 months, or something like that. That’s $25 a month, it’s a lot of money if you’re making $50.

What we’ve done is, we finance the home, but we also are coordinating an extra 100, 150 square meters around the home of agricultural production. So things that don’t really thrive in a greenhouse, like root crops, so potatoes, and onions, carrots, things that there’s no benefit to being in a greenhouse, we do open field, and then we cultivate that 100 square meters minimum around a home, and that generates essentially $20 to $30 a month.

Now, you’re talking about a manageable plot, someone earning $50 a month from some other source. Now, they in their family can live in $1,000 house, and they can actually pay for that home. That means that’s their home, that’s their plot. What we’ve really focused on in terms of our mortgage is, it’s essentially a piece of a larger puzzle. The larger puzzle is affordability, and the pieces of that puzzle are essentially, what are the specific elements that can contribute to the ability of a low-income, but income-working family to actually start to build wealth to store value. That is at the heart of Small Farms Cities.

Jeffrey Mason: I recall, I won’t say where but we once went on a site visit to a different city project, and we’re chatting with them, and they were stunned at the sort of price point that you were able to achieve. I think it is really impressive what you guys have been able to do there in terms of driving housing accessibility for people at sort of the bottom of the economic ladder.

Jon Vandenheuvel: Well, the fun part is that a $1,000 home, it’s very, very basic, obviously. But for another $200, you can add a bathroom to the home. We don’t have indoor plumbing, or a bathroom, because that is $1,500 all-in. But if you are earning $60 a month or $70 a month, you can afford that right up front. If you’re not earning that money, but you are learning the trades and the skills, you can build it yourself. We put that right into the design. I think, modularity, those things that make economic sense, it’s like going to a restaurant. You want the basic meal. But oh, “Do you want fries with that? Do you want this? Do you want that?” Building options, so you have an affordable baseline.

But then, because you have the baseline, then let’s say, you earn an extra $10 a month, or $15 a month. Now, you can have this, and you can have that, and you can have the other thing, you can add a room. It is a little shocking, maybe to look at $1,000. I’ll tell you, to get a home, a decent home with a proper seal, and good protection against the elements, and mosquitoes, and water, and a solid foundation, and a metal roof, and a veranda, and living space. When it all comes together, it is a bit shocking that we can build a home for $1,000, but we can, and we have, and we are right now. That’s in Malawi with a very, very challenging supply chain, and a devalued kwacha, and all the other headwinds that you face.

Jeffrey Mason: You mentioned modularity and how you’re both at the individual house level, there are things you can add on to, and expand to. How does the entire small farm city itself — what does that look like at that level in terms of modularity and ability to scale?

Jon Vandenheuvel: Yes. The project I just described was our first project. Our next project is now under construction, and it’s a larger space, it’s about a 20-acre, eight-hectare space.

Jeffrey Mason: How big is the current space by comparison?

Jon Vandenheuvel: Three hectares, or seven acres. The space itself is a little less than three times bigger. What we’re able to do is we’re able to then build in more elements. It’s about the same number of greenhouses. But what we’re doing right now is we’re building plots that are 400 square meters, instead of 100 square meters. Because the new residents of the current site won’t have a full-time job with Small Farm Cities. They won’t be earning the $50 a month with Small Farm Cities, but because they have now 400 square meters, this is the modularity aspect of it. Because now, with 400 square meters, they’re actually able to earn $100, $120 a month.

Well, they’re no longer poor. I mean, to some extent, you might say they’re no longer poor. Because now, they’re essentially on a path to accumulating on an annual basis, hundreds, and hundreds of dollars of margin. The key point with modularity is actually contributing to margin, because the more you can essentially kill multiple birds with one stone, or achieve economies of scale. I’ve always felt from my first project in Ghana 15 years ago. Economies of scale is an economic principle or law, it’s like gravity. You can like it, you cannot like — It doesn’t really matter. I mean, gravity is gravity.

Economies of scale, it’s not a matter of an opinion and, “Ohm boy, it should be nice if –” Now, economies of scale is an economic principle, and it doesn’t matter if you have a communist country, a monarchy, a democracy. Economies of scale is what it is. It’s an economic law. The challenge in the informal economy, and the unbankable economy, is that, how do you access the benefits of economies of scale? The thing is, Africa is part of the global economy. The only problem is that Africa collectively is a price taker, instead of a price giver, or setter. They’re a price taker. What happens is that, when you then reverse engineer this to the bottom of the economic pyramid, and you have hundreds and millions of people who are essentially left out of the mainstream of economic production, and they are price takers, they are victims of these larger systems. They have no ability to achieve economies of scale. They have no ability to be competitive, and the market always rewards value.

If you can’t be competitive, how are you supposed to provide value? That’s why Africa imports $50 to $100 billion of food every year that they could definitely be growing themselves. It’s because, on a massive scale, you do not have access to the benefits of economies of scale. What we’re creating by coordinating, and bringing really micro municipal infrastructure. Now, I’m using the municipal word, which is relevant to the Charter Cities conversation. This is the only way that the African mainstream working-class producer can become a real full member of the global economy. It’s not a matter of, is this a good idea, bad idea, whatever. It’s like, no, these are economic principles.

The market always rewards value. The Chinese Communist Party knows that. Democratic Western free-market economists know that. The only question is, what are the principles upon which you can organize economic actors, and known as Small Farm Cities is doing what we’re doing in real-time, as we are organizing economic actors. It’s just that we’re organizing those who have up to this point essentially been treated as third-class citizens, just producing widgets for a larger aggregator who then sucks all the value and projects that value into the global economy. What we’re doing is, we’re saying, wait a second, let’s create infrastructure systems, hard infrastructure, soft infrastructure, so that everyone can access the benefits of economies of scale. That way, they can start producing a product with value to the market on a competitive basis, and start to get ahead.

Jeffrey Mason: You started to allude to your second Small Farm Cities project. When asked, how do you source talent? There’s obviously a lot of very talented people in Africa, in Malawi, in every country, and that’s often difficult to access, or it’s not concentrated. There is no equivalent San Francisco Bay Area in Malawi or anywhere in the continent. But yes, I think you guys have done a really good job of being able to identify source and also develop talent locally in Malawi. Can you talk about how you find good people, and the sorts of training for your employees, and residents that you guys have been doing?

Jon Vandenheuvel: Sure. Well, honestly, Jeff, I mean, this is the most exciting part of what we’ve been able to do in Malawi, is organize a team. I mean, like a truly a world-class team. I obviously credit my co-founder, Leif Van Grinsven, for really being the sort of organizer, and developer of our management, and our operational talent. Our approach has been a blended approach, you might say. What I’m referring to is, number one, everybody is a professional, even someone who doesn’t have any formal education, even someone who may have been referred to as a casual labourer. Professionalism starts before someone is even hired. That tone is set, and valuing a person, they might be earning at the beginning $50 a month, but there’s an assumption that we make as a company, that everyone is capable of achieving more if they’re willing to put in the time and effort, and if we’re willing to put in the time and effort to make it so.

Now, we have basically three categories of employee, if you will. We have the working-class professional, no formal education, or very little formal education. Then, we have skilled trades. Welders, plumbers, carpenters, those who have trade skills, and then we have sort of a blended managerial talent pool, which are university graduates. They may have majored in communications, or agronomy, or Bible, or whatever. What we’re looking for are leaders and servant leaders, those who have a high degree of human respect, and you might say, social capital.

We’re looking especially at the managerial ranks for those who can just as easily sit in a boardroom of a national bank or meet with the president of the country and then sit under a tree in a village and be equally conversational and relational in all manner. Our team is that. We have gifted people who are fun. We put a premium on fun, we put a premium on having a good time, and we put a premium on working very, very hard. Then, we put a very big premium on training and development. Our main center at Small Farm Cities is the town and tech center. The technology, we use Starlink, we use the satellite internet, and everyone has access to that.

We’ve got a young man right now, working greenhouse, 40-plus hours a week. Then, in the evenings, he’s studying coding, and getting an online degree. We’ve got multiple people getting online degrees. We are a very young company. I’m the old man. Even Leif, who’s only 27, almost 28 is almost the old man. It’s a very young culture. We’re looking for young men and women who want to learn, want to have a good time, want to work hard, and want to really contribute to the development of the country. So yes, I mean, I wouldn’t say there’s any secret sauce to it. It’s just a lot of passion, a lot of intentionality, and a lot of respect, just peer-to-peer respect.

Jeffrey Mason: I think that’s really exciting what you guys have been able to do, and what you’re continuing to do. Imagine, it’s going to continue even at bigger scale in the next community that you guys are planning. So just tell us about the new one that’s been in the works now. Sure.

Jon Vandenheuvel: Sure. One of the key hypotheses that we’ve had to prove is that the model can scale. We would like to take a bigger bite of that and push it to 5,000 people, 10,000 people. Those plans are now in the works. The step we’re taking right now, I think will position us to get to the 5,000, 10,000-person scale. That is, we are building currently in an area about 40 kilometres north and west of Lilongwe, the capital city, and we are right next to what is evolving or developing as one of the world’s largest new titanium mining operations. The mine is not yet operational and probably won’t be for another 18 to 24 months, but all the groundwork has been laid. It’s not a secret. It’s sovereign metals. It’s a publicly traded company from Australia. All of this is public information, sovereign metals, titanium, mining. Rio Tinto is a major shareholder. It’s a big-time, new rutile graphite, titanium operation that is now coming online.

What we’re doing here in the current project is we’re building. I mean, we’re building essentially, a 2.5 or 3x version of what we’ve just built. But where we’re building, it opens up now additional doors. The additional doors, I would describe as light industrial. Light industrial, the mine is pretty much heavy industry, and the mine is going to be kind of investing in heavier industrial elements, things like electricity, water systems. I mean, it’s big time, it’s going to be a billion-dollar operation. But what we can do by locating an agricultural cluster right next to that is we can now begin to diversify what is really a small farm city. I mean, is a small farm city more about the small farm, or is it more about the city? It’s like, all of the above.

Because the fact of matter is, not everybody in a small farm city already is a farmer. What we’re building right now, the platform that we’re building will be very conducive to the development of support services that can be offered to the mining operation, hospitality, and housing. They’re going to have a thousand employees, they’re going to be engineers, scientists, and product developers. What we’re doing with light industrial is we’re basically saying, “Look, we already build our own furniture. That means we’re already working with wood, we’re already working with metal. What we’re going to be investing in now is some very, very basic plastic injection moulding equipment.”

Malawi is a rubber producer. In the northern part of Malawi, they produce rubber. Between chemicals, wood, metals, plastics, rubber, you have essentially all the raw materials to build a very diversified industrial base. The other piece of this that I think is very interesting is that the mining area, the area of proven roof tile graphite deposit is a very large area. The area is probably 20,000 to 25,000 hectares. Well, 25,000 hectares is the size of Taipei. Amsterdam is 22,000 hectares. An area the size of Kampala, St. Louis, Missouri is 18,000 hectares. That’s just the area of where they know there’s titanium.

The idea that over the next 25 to 50 years, that a new city, really, a modern city that’s designed for the people, that that could be built right here in this space is extremely realistic. In fact, it needs to happen. Because if it doesn’t happen, then you end up with what you have all across Africa with mines, which is, you have a big hole in the ground, and you haven’t developed the community, you haven’t developed the area. So you end up with environmental mess, you end up with a human mass, squatters, just all kinds of issues.

Jeffrey Mason: There’s no coordination to get the benefits of the municipal infrastructure.

Jon Vandenheuvel: Exactly. Exactly. We look at this current project as we’re just getting organized. There’s a tremendous opportunity to develop different kinds of industrial tracks. This is I think, one of the key principles for Charter Cities to keep in mind across Africa, is what’s in the charter. You can build industries without building cities. We have this all over Africa. You have copper mining, you’ve got rubber plantations, coffee, and tea estates, you’ve got commodity-based industrial investments all over Africa, but you don’t have towns. You’ve got Nairobi, and then you have the bush. So you got Kinshasa, then the bush.

This whole concept of leveraging industry, to then build a community, this has just not been done. You can have industry without building communities, you can just extract the resources and send it to the market. The people are just an afterthought. Look at the cocoa sector in Ghana, in Ivory Coast. I mean, cocoa farmers make less money, adjusted for inflation. They make less money today than they did 100 years ago. They’re not going anywhere. The cocoa industry should be embarrassed at how little development they have brought to the major cocoa-producing countries in Africa. You can have industry without community. The colonial methodology has flourished for decades, even centuries in this way. It is now time to build the communities and build the cities that leverage these industries. Because the thing is, you can’t build communities without industry. So you can have industry without communities, but you can’t have communities without industry. So you can have a charter, a great law, a great governance, but you got to have the industry.

Our focus with Small Farm Cities is to develop industrial production. It is to create value. The charter is where the value can be then recognized in a global context, legally recognized. What good is it to create value if there’s no legal recognition of that value? It’s like Hernando de Soto, with the book, The Mystery of Capital. I mean, he hits the nail on the head, which is the world’s poor are sitting on trillions of dollars of dead capital, dormant capital. Well, the only way to bring that alive is with a charter. From our perspective, we’re kind of in the grinder here of saying, “Okay. What does this look like?”

Then, the second key point here is accessibility, because it’s one thing to kind of then build an upscale gated community, and then leave everybody out. A lot of industrial zones around Africa, you bust in the workers, and then you bust them out. They’re basically squatting wherever they are, and you’re not building the towns, you’re not building the communities. What we hope we can do here with Small Farm Cities, Nsaru and Kasiya in Malawi west of the capital, is be a contributor, be an organizer of a way forward, a new way of thinking. That’s a win-win. Sort of all of that conversation, and then the policy, and all that framework, I’m kind of calling a charter. It just makes sense that that be the relationship between sort of the industrial development, the accessibility, and then the governance that sort of makes a good deal for everybody.

Jeffrey Mason: On this topic, I’m sure you know the government in Malawi just recently passed an updated Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Law. And one of the components of this that we’ve found really exciting is that in addition to your traditional industrial park, export processing zone, technology park, et cetera, is that it allows cities and urban areas to enjoy the full benefits of a special economic zone regime. Is this something that with your new community that you’re planning to take advantage of? And the sort of more broadly, what is your interfacing to the extent that you do, your interfacing with government look like?

Jon Vandenheuvel: Sure. I think this was a very significant development in Malawi, one that I believe the Charter Cities Institute was a key contributor to. That is, that the Special Economic Zone Law factors residential urban development. So it really is an advancement, as you might call it. I think that many colleagues with Charter Cities have called it Special Economic Zones 2.0. That is where it’s not just an industrial park, it’s a foundation to build a healthy blended community. That law, it’s a very exciting development in Malawi. We plan to pursue that for sure. We will absolutely pursue designation and recognition under this law.

I would only say that I’m not sure yet, honestly, chicken or egg. Because the way we’ve built so far, we could never have waited for some kind of designation like this. We’ve developed on just private property and private titled property, and then everything is really governed by contract between parties. You might say we have charter by contract, because it’s private land, and everything is governed by contract. Our relationship with the land, our relationship with each other, everything is governed by contract, and that’s okay. I think that’s okay at this scale. But under the new policy, the opportunity to kind of now bring in a larger regional focus, a more integrated kind of model where there are more players, more actors, it’s more complex set of relationships. What I don’t know, honestly is, I can’t predict how long it will take, let’s say, for us to get this recognition, or what hurdles will be put in place. The law is actually a bit ambiguous in terms of its implementation.

Jeffrey Mason: Yes. We’re going to need some supplemental regulations.

Jon Vandenheuvel: Exactly. I don’t know. What I hope we can kind of do is become a coalition of aligned stakeholders. Our residents, our employees, ourselves, other collaborators, the government themselves. We have a good working relationship with the National Planning Commission, with Thomas Munthali, the Director General there. He’s been great to work with. I think he has a real vision for the future of new cities and Malawi. The NPC was very involved in making sure that this language of city development and secondary cities is baked right into this new Special Economic Zone Law.

On paper, you might say, stars are lined up. Now, it’s a matter of execution, implementation. Everyone hopefully is aligned in terms of what’s our objective. Our objective is an inclusive, healthy, balanced economic platform that makes investment by foreign investment, as well as local investment makes it very, very favourable good conditions, very reliable regulatory framework. The ability to think in terms of larger investments in power and water, getting into the multiple megawatt power solutions, et cetera. So it really is an exciting moment, but also a moment of uncharted territory.

Jeffrey Mason: Yes, that’s definitely an exciting opportunity. Now, earlier, you briefly alluded to a previous project you had worked on in Ghana. Could you talk about what lessons you learned from that that you’ve fed into Small Farm Cities? Also, why Malawi?

Jon Vandenheuvel: On the first question, on the lessons, full disclosure, I did write a book called Africa Risk Dashboard. So I’ve got like 50 podcasts worth of lessons, but let me just hit the highlight. The highlight is essentially what I alluded to earlier, which is that, economies of scale, and affordability, it’s a system of many different factors. The most important takeaway from our investments in Ghana is that, when you set out to invest in agriculture, the agriculture is just one part of it. The transport, the logistics, the finances, the currency. I mean, we’ve developed a dashboard, legal issues, contractual, legal policy issues, financial issues, operational issues, which is both hard infrastructure, soft infrastructure, environmental issues, social issues, and then safety and security.

The reason we came up with that is because, when you’re an investor, you can’t go to the ministry of all of that. There’s not the ministry of all of that. You’ve got the Minister of Agriculture, but he doesn’t have anything to say about transport. Go to the Minister of Transport, but he doesn’t have anything to say about electricity, and on, and on, it goes. Not to mention like education, and health, and housing. A systems problem absolutely demands a system solution. What happened in Ghana is, we realized, after just a matter of maybe five to eight months, that we weren’t building a farm, we were building like a city. Because a city is a system, a city essentially is like a reconciliation of all of the above. Our work in Ghana sort of took us into, through a long story I won’t go into, took us into a collaboration with the MIT School of Architecture and Urban Planning.

We work very closely with a Kenyan American professor named Calestous Juma, who was a faculty of Harvard Kennedy School, but then was a visiting professor, the Martin Luther King, Jr, visiting professor at MIT. We organized the lab essentially around this. It really took me into the urban planning space. I’m not an urban planner, but it took us squarely into the urban planning space, sort of the civil engineering space. So coming out of Ghana was a strong view of the necessity and the importance of infrastructure, and systems in order to make agriculture viable, African agriculture viable.

Probably, one of the key kind of takeaways boiled down to is was it cheaper for a ton of corn to get from Minnesota to Ghana, than for us to produce a ton of corn in Ghana, and get to Ghana port. The fact is, yes, it’s cheaper to produce and deliver a ton of corn from Minnesota on the Mississippi River, through New Orleans, on a freighter, deliver it in a bulk freighter to the port of Tema in Ghana, cheaper than for most Ghanaian farmers to produce that same time, somewhere in the middle or north of the country, and deliver it to the exact same spot. Now, that’s not a seasonal problem. That’s a structural problem. The problem is scales.

Maize production, soybean production in Africa suffers greatly, not because of just seed, and fertilizer, or the kind of work gets over. Climate change is a real thing, but it becomes almost like an excuse to suck, and did not figure out other things. It’s like, “Oh, God, we got climate change. We need more money.” It’s like, well, more money on one piece of the problem isn’t going to solve the problem. It’s a systems problem. It requires a system solution. Coming out of Ghana, in this very expensive test on our part, is where we come up with Small Farm Cities. Because a small farm city essentially takes all those questions and boils them down to, “Okay, what do we need to do to make the whole system work?”

What brought me to Malawi was an invitation that related to Malawi’s dependence on tobacco as a cash crop. The fact that global demand for tobacco is going down and it really is impacting the Malawi economy. Because of our work in Ghana and work in other places, Dubai and so forth, I was invited to kind of weigh in on that. That’s something that I did for a few years working with an organization called the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. Its purpose was to kind of envision a more diversified Malawi economy. My recommendation was to not just swap tobacco for maize or, “Okay, you’re growing maize, why don’t you grow potatoes?” It’s like, “No.”

If you’re barely getting by growing tobacco, is it really an upgrade to just barely get by growing maize? Or is there something more substantial that we should be looking at here? That was really a recommendation to do Small Farm Cities, that would be a small f, small c, small farm cities. Through, actually, your organization, our organization, Jeff, Charter Cities, I was introduced to Patri Friedman, the GP of Pronomos Capital at a Charter Cities event. We started to discuss new cities, and I said, “Look, in Malawi, what we really need is like a Chicago-style hub, kind of a Chicago-style agri industrial hub. It’s water, and rail, and industrial, and residential. That’s kind of what we need.” He said, “Well, why don’t we do it?” That was 2021.

Now, it’s 2023, and we’re up, and running. That’s why Malawi. The original Small Farm City model, I had sort of with friends, and colleagues, from MIT, and my company, we had sort of envisioned this for Southern Somalia. We originally came up with the idea as the result of an announcement by President Kenyatta of Kenya that he was going to shut down the Dadaab refugee camp in the Garissa area in Eastern Kenya and was going to send maybe 150,000, 200,000 Somali refugees back to Southern Somalia in an extremely fragile situation. We were invited by the Somali government, and by the Juba State and by the Southwest State of Somalia to conceptualize, what would you do. Our view was, you would build basically safe economic zones, you would build zones that could be defended, but then within the zone really would emphasize the relationship between home ownership, and housing, and agricultural production, and then starting with light industrial development.

The original concept was actually under pressure to envision what would you do with 50,000, 100,000 refugees if they were forcibly sent back to Southern Somalia? So President Kenyatta, then, that was all resolved, and Dadaab is still up, and the people are still trapped in Dadaab refugee camp. We never did build this for Southern Somalia. But that was like 2018, 2019. The idea was valid then and it’s valid now.

Jeffrey Mason: Yes, it’s something interesting, actually. We just saw a few months back, Kenya – I can’t remember off the top my head if it was one or two, but they actually went ahead and chose to declare two refugee camps as formally as municipalities, so they can start to transition away from that sort of helpless camp model, to something that can actually be economically productive, and endow the people living there with the least some semblance of economic and other rights. I think it’s interesting to see how this sort of refugee cities and similar concepts are going to emerge.

Jon Vandenheuvel: I agree, yes.

Jeffrey Mason: Two final questions before we wrap up. First, in a past life, you were a senior staffer in the House of Representatives. How does one go from working on the hill, to building cities in Malawi? The second is that, we know you’re very proud of your Dutch heritage. How does that influence your work?

Jon Vandenheuvel: How does a hill staffer, a political hack end up in Africa developing agricultural industrial cities? That’s a tough question. I’m going to kind of give you a form of an answer that is probably very unsatisfactory. When I worked on Capitol Hill, I worked with, the last four years was with a congressman from Oklahoma named JC Watts. JC African-American congressman from Oklahoma. He was an Oklahoma Sooner football star, a great athletes, visionary, entrepreneur, just very focused on economic freedom as the way to beat poverty. I would say, sort of philosophically, what had been happening for me in terms of working in public policy was economic freedom, and opportunity, and entrepreneurship. That’s sort of the only way to really sustainably beat poverty. But too few people have the tools to make that happen.

So, my work on Capitol Hill was focused on American poverty, kind of American entrapment, inner cities, the whole criminal justice system, the whole mess of mass incarceration of African-American, males especially. And then the resulting sort of economic entrapment that continues to this day to afflict a pain and stunt the development of, in particular, the African-American community, but really all communities for which mass incarceration and poverty become sort of the perfect storm.

I was invited just as an afterthought in 2001 to go on a congressional trade mission to Africa. I had never been there. Because I was staff director of the Republican Conference in the house, a leadership staff position, I got to just go on what you might call a junket. We flew from Andrews Air Force Base to Senegal, and then Nigeria, and then Ghana, and then we were back in five days. It’s like, “Yes, okay, I’ve been to Africa.” But on the last day, we were in Nigeria, in Lagos, kind of looking over the city. I was just like blown away. Like, what’s going on here? I mean, all this energy, all this excitement, and then all this chaos, it’s like, what is this?

You might say that what began as a curiosity became an all-out obsession by 2008. I really started to just kind of pour myself into the idea that well, wait a second, entrapment’s entrapment. It could be in the inner city of Baltimore, or it could be Lagos, Nigeria. I just decided at that time, I was 39, and naive, and probably a little bit arrogant. I thought, “You know what, The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is not going to hire me. World Vision is not going to hire me. I have no credit. I’m not an Africa junkie. But I have a couple of bucks. I think I’m just going to go and just pour myself into this, and just see if we can make Africa work. And if I fail, I fail.” So it’s kind of something a 39-year-old might think.

It’s a long, crazy story. Pretty insane. I would have never imagined that 15 years later, I was still doing what I’m doing. I’m a God guy, I’m pretty faith-oriented, and I believe God’s got a higher purpose. I’ve made a lot of mistakes, I’ve had a lot of failure. That’s the shortest version I can possibly come up with, as to why a political hack ends up doing what he’s doing in Africa.

Jeffrey Mason: I think even the short version, I think it’s a great story.

Jon Vandenheuvel: Right on the edge of pure lunacy. But every day is fun, and every day is an adventure. Even if the end of the day I’m like, crying.

Jeffrey Mason: Well, it seems like the way things are going now, maybe fewer tears than there used to be. More smiles these days.

Jon Vandenheuvel: It is coming together and we’re really excited. But we’re not out of the woods yet, we got a lot to prove. It’s a big task, but we got a great team. I’ve really appreciated the encouragement of Charter Cities and kind of the alignment of your thinking, our thinking, and it’s been fun.

Jeffrey Mason: Yes, it’s been awesome for us to work with you as well, and we’re excited for what’s to come. Thanks for chatting, Jon.

Jon Vandenheuvel: Hey, thanks a lot, Jeff. Yes, take care.

[END OF INTERVIEW]

Kurtis Lockhart: Thanks so much for listening. We love engaging with our listeners, so please always feel free to reach out. Contact information is listed in the show notes. To find out more about the work of the Charter Cities Institute, please follow us on social media, or visit chartercitiesinstitute.org.

[END]