Dar es Salaam: Communities and Activities along the Mbezi

Image 1: A view of the skyline of Dar es Salaam

The Blog Post Series

The blog post series “When a River Crosses a City” will highlight various metropolises around the world and their respective relationships with waterways, taking the readers through a common story of different realities deepening the comprehension of existing synergies.

Introduction

River management and design is a great challenge of contemporary landscape urbanism. Cities have been developing along waterways for centuries. The relationship between metropolises and flowing water bodies has evolved over time, transforming with the societal role of urban agglomerations, natural elements and ecosystems. Nowadays searching for a balance among modern cities’ needs and thriving waterways is a complex task aggravated by the effects of climate change.

The evolution of waterways in western cities presents a pattern where communities initially connected with rivers evolved into neighborhoods crossing canalized and abandoned streams. In fact, the inability to combine some fundamental aspects of cities such as permanence and density with natural behaviors of rivers as flooding and erosion has led to the aforementioned approach.

The concept of river re-naturalization has been gaining traction in Europe, trying to prioritize the natural behaviors of waterways and restoration of ecosystems within urban realities. Rehabilitation approaches are significant steps towards new, more sustainable urban river realities. However, re-naturalization strategies are specific to a certain life stage of waterways.

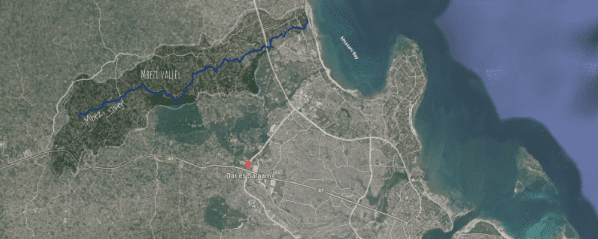

This blog post will describe the synergy between a stream and its dwellers, located in the northern part of the city of Dar es Salaam. The Mbezi River context provides a great example showcasing the needs of new and diversified approaches to river design strategies, while highlighting the complexity and diversity often characterizing river realities.

The Context

Dar Es Salaam, the capital of Tanzania, has an estimated population of 6 million inhabitants and it is expected to reach more than 10 million people sometime before 2030. The Mbezi River is one of multiple natural elements entangling with the city structure and contributing to urban dynamics. Rapid urbanization has been shaping Mbezi development for years.

Image 2: The Mbezi Valley and river.

The river is currently facing many challenges related to human cohabitation. The waterway has become a magnet for informal dwellers relying on its ecosystem. Natural river behaviors such as erosion and flooding have intensified due to climate change, threatening the local communities. Pollution issues related to garbage disposal are also arising, compromising the quality of the services.

The River

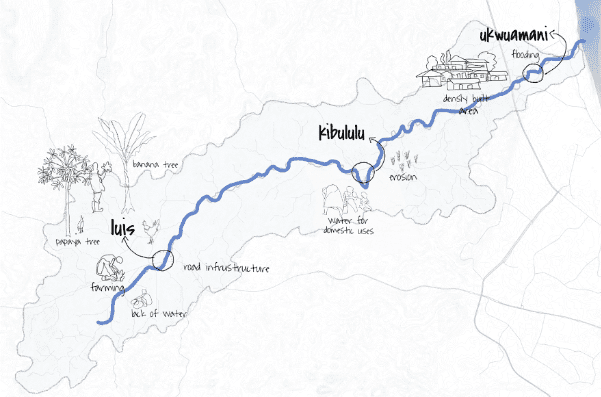

The Mbezi has a relatively short flow, however a wide variety of landscape shifts are displayed along its edges. The river has a seasonal profile; running as a powerful water body during the rainy season and functioning as a clear road in the dry times. The dwellers living along the river line have different relationships with the waterway, each presenting their own history and unique set of challenges.

Image 3: Map of the Mbezi valley with its most characteristic aspects.

Synergies and Challenges

Luis

The majority of farmers are located upstream in the cluster of Luis. The settlers of this area developed a deep understanding and respect for the surrounding environment. Over time, a different population segment moved in, encouraged by urban development. The newcomers built houses and paved surfaces. Such practices changed the areas’ infiltration rate, increasing run-off and affecting groundwater levels, making it hard to fetch water during dry periods. Inhabitants are forced to dig holes directly in the river bed to find water or install rain harvesting tanks when feasible.

Image 4: A view of Luis.

Image 5: Housing typology in Luis.

Image 6: locals dig holes directly in the riverbed to find water.

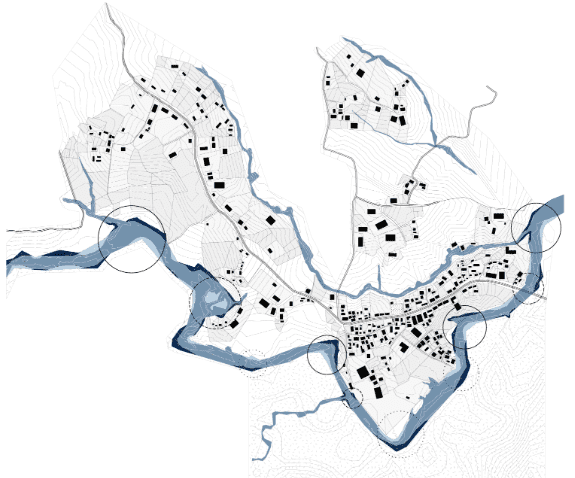

Kibululu

The people of Kibululu are located in the middle stream area and are involved in both farming and petty trading activities. The population increase in the neighborhood pushed for the construction of more houses on the edges of the river banks. The structures are heavily exposed to erosion and the settlers often lose their homes and plots due to landslides.

Image 7: Map of Kibululu with the main erosion affected spots circled.

Image 8: Houses built at the edge of the riverbed.

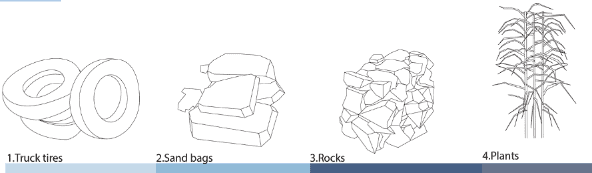

The locals have tried many coping techniques to contain the erosion. Truck tires and sandbags are piled to create retention walls. Trash and other available materials are compacted into the soil to reinforce it. The inhabitants also experimented with plantation strategies based on vegetation species with particular root systems helping to strengthen the soil.

Image 9: Different coping mechanisms experimented by the locals.

Image 10: sandbags used to avoid erosion.

Image 11: Planting strategies.

Ukwmani

The inhabitants of the informal settlement of Ukwmani are a historic community located in the river plain close to the outlet. The government listed the space as a flood risk zone and forbade anyone to live or build there. The authority started relocation efforts for the residents; owners were offered compensation but the majority refused to accept the move. The river in this area is used as a waste dump, farmland, and backyard. The people of Ukwamani face regular sudden floods , the most sudden event among the river behaviors. Mitigation is the only available solution, since the issue should be tackled at the source.

Image 12: A view of Ukwamani neighborhood.

Image 13: Damages caused by flooding events.

Image 14: The riverbed is used as a trash dumping site.

Image 15: Damages caused by flooding events.

Quarry mining

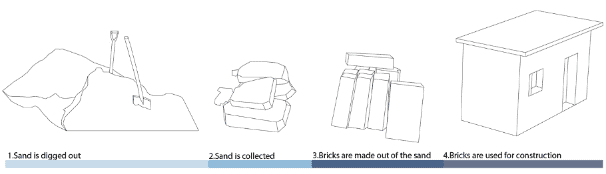

Sand miners are seasonal workers present in the middle and lower parts of the river. They dig sand out from the dried river bed to sell it as raw material for brick making. Mining is a profitable business connected with the river , but it has been declared illegal to protect the banks. The banning of the practice led to the creation of criminal organizations managing the business.

Image 16: The process of quarry mining in Mbezi.

Conclusions

The Mbezi is a collector of a diverse range of urban dwellers relying on different activities to support themselves and facing various challenges in relation to the river. The Mbezi catchment story can serve as a reflection point for what are some impellent aspects to take in account in the field of river management.

The general understanding of re-naturalization approach does not feel appropriate for the Mbezi context, since the waterway itself has not yet undergone any of the usual heavy engineering coping interventions (e.g channelisation or a dige) which have shown to negatively impact both the social role of waterways in communities as well as the river health.

The Mbezi valley and inhabitants are facing different challenges, such as flooding, erosion and water scarcity, which are pushing for changes. How those necessary transformations will take place and in which form growth will happen is hard to picture, based on current waterways design practices. Observing the riverside it is clear that the Mbezi valley yearns for a positive social, environmental and economic future where communities can flourish along the river in a balanced synergy.

Image 17: The Mbezi used as a road during the dry season.