Wildebeest and lions?

Let me first introduce the African Railway Renaissance.

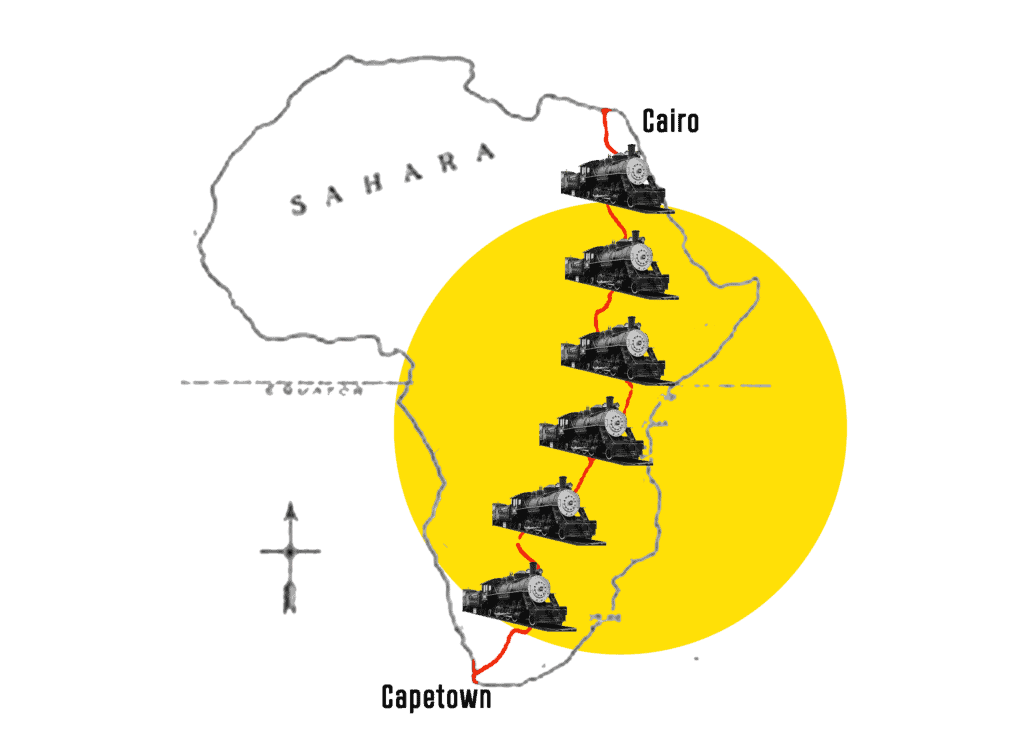

During the colonial era Britain dreamed of building a top (Cairo) to bottom (Cape Town) railway through Africa. The French, Belgians and Germans colonized inconvenient chunks of Africa in the middle. The vision faded. In the 1970s the Chinese had another go, building the TAZARA Railway to connect Zambia to the Tanzanian coast in the north. By 2014 the TAZARA was running at an estimated 2% capacity.

In 2022 railways are back in Africa!

The 2015 launched African Union (AU) vision for 2063 ‘The Africa We Want’ says a “Pan-African High Speed Train Network will connect all the major cities of the continent”.

You might be wondering when the wildebeest comes in?

Of course! But let me first assure the reader, the Railway Renaissance does have real substance in solid steel.

The African Development Bank (AfDB), the World Bank (WB), the US government, and the Chinese inspired Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in particular have all promised financial backing. The trains have started running. In 2017 the $3.8 billion 480 km line from Nairobi to Mombasa (Kenya) and $4.5 billion line from Addis Ababa (Ethiopia) to Djibouti were both inaugurated. In September 2021 Egypt signed an $8.7 billion deal with the German company Siemens to build a 1,800 km electric railway between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean where trains would link 60 cities and reach a top speed of 250 km per hour. High speed trains are already whishing through Morocco, Nigeria, and Tunisia.

Wildebeest???

I am coming to the wildebeest. But let me first explain how I intend to think about the likely economic impact of the railway renaissance in Africa. Before you continue reading there is something you have to take on trust or else read the full justification in a longer paper. We can learn about the likely economic impact of railways in Ethiopia today by glancing back at railway building in nineteenth century Sweden.

Hmmm! I can imagine raised eyebrows and doubting sighs.

Well not just Sweden. In fact the entire history of railway building. From the faltering clunky explosion prone engines in 1830s Britain, to the continent crossing Transcontinental Railway in the US (opened 1869), the slave-and-prisoner built Trans-Siberian Railway in Russia (opened 1906), to the 70,000 km long arrogant totem of colonial Britain in India, to the modernizing impulse of nineteenth century Japanese railways, to the high-technology contemporary high-speed railways in China. Fascinating stories, but also instructive. These railways were built when the countries in question were as poor and rural as contemporary Africa; the railways (like the AU vision) were about crossing continents; the railways were financed by the global powers of the day – for Britain and France in the nineteenth century and China today.

Before we get into the wildebeest metaphor, let’s talk dollars, or rather the lack of them.

For some the optimism of the African Railway Renaissance has deflated quicker than a badly tied party balloon. In 2019 the Addis-Djibouti line earned $40 million in revenue against operating costs of $70 million. By May 2020 the Kenyan line had accumulated operating losses of $200 million.

Before we finally get to the wildebeest I need to digress and talk about lions. Railways have physical presence; they are magnificent; they are like an economic lion. We could imagine an African railway roaring the economy onward. This is a mistake!

History tells us with striking monotonous regularity that railways run on squeezed profit margins and frequently go bankrupt.

The super competitive railway system in nineteenth century Britain earned low profits as companies competed to transport mainly poor passengers around the burgeoning network. In Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay across the late nineteenth and early twentieth century’s railways earned minimal profits or made losses. In 1842 The Erie Railway defaulted on interest payments and the government of New York canceled its $3 million debt to ensure construction work could continue. The Erie railway eventually suffered five bankruptcies. During 1873 and 1874 nearly 100 railway companies defaulted on more than $400 million worth of debt and by 1878 railway stock had fallen by 60%. In 1890 European investors fled from all forms of railway finance after Argentinian railways defaulted on debt payments. In the US 89 out of the 364 railroads – representing 40,000 miles or 25% of the national total – went bankrupt, including the Transcontinental Union Pacific Railway.

There is no great mystery why railways go bankrupt. Railways are not lions. The best safari resident to compare a railway to is the humble wildebeest (finally!) – the animal seen lumbering around the savannah, wallowing lazily in mud and invariably being eaten by more charismatic animals – lions, cheetahs, hyenas, or vultures. That is exactly the economic function of railways. Railways require huge up-front investment and take a long time to build. Railways exist to create profitable investment opportunities elsewhere, to transport manufactured goods to port, or food grains to urban areas or potential workers from small towns to a capital city. Railways are the wildebeest that the true engines of growth feed upon to create exports, employment and income elsewhere. In the US railways were built ahead of demand, hoping that farmer-settlers would migrate to a region to generate a demand for railway services. In Canada railway construction peaked in the final decades of the nineteenth century but wheat production and rail traffic only increased in the second decade of the twentieth century. In Russia the Trans-Siberian railway was built across empty land, never making money but transforming Siberia from a place for criminals in exile to a place for migrants to work in industry and agriculture. Three million people migrated to Siberia between 1906 and 1914.

The very idea of a railway renaissance; the glossy videos produced about the African Union; the foregrounding of railways as the flashy showpiece of a wider Rise of Africa is a mistake. The New York Times did exactly this in 2022 when they reported on the new Kenyan railway system.

“Five years after its launch, the railway has become associated with debt, dysfunction and criminal inquiries.”

There is no such thing as a Railway Renaissance. We should avert our gaze from railways. We should forget about the profit and loss columns of individual lines. Railways, like education, like broadband internet, like good governance are at best only an input into the real fundamentals of growth and development. The questions we need to ask are the same we have always been asking. What is Africa exporting? What is Africa producing? How much is Africa investing? What is happening to African productivity?

We must expect and endure financial problems and bankruptcy of African railways. We must hope that the vision of the African Union and the patience and financial backing of the Chinese BRI are sufficient to keep building railways, to extend lines to connect ports, cities and deposits of raw materials even when railways don’t pay for themselves. It is the long-term wealth created by urbanization, industrialization and export-led growth that will create the national African wealth to pay for the railways.

The lions, cheetahs, hyenas and vultures wouldn’t look so glossy and photogenic without the humble wildebeest would they?