According to Richard Florida, we have entered the Creative Age. In his seminal work, The Rise of the Creative Class, Florida argues that creativity has become the lifeblood of post-industrial Western society, subsequently giving rise to the “Creative Class.” While Florida’s conceptualization of the Creative Class emphasizes the accepted role of creativity in fostering economic growth and urban development, his classification of a distinct Creative Class disregards the complexities of social and economic disparities. To build truly creative cities, the focus must shift towards inclusive policies that cultivate creativity in all facets of society, prioritize quality of life for all residents, and support diverse local initiatives.

Overview

Florida believes that a new social class is on the rise. He posits that higher demand for new ideas, technologies, and content and the increase in workers who are “paid to use their minds” has led to the emergence of the Creative Class. Florida’s Creative Class is not limited to a specific demographic or industry but encompasses a variety of occupations that rely on creativity and knowledge. This wide-ranging group includes the “super creative core,” composed of people who “work in science and engineering, architecture and design, education, arts, music, and entertainment,” and the “creative professionals,” who work in “business and finance, law, health care, and related fields.” Numbering over 40 million in the United States, the Creative Class comprises a third of the US workforce, but “roughly half of all US wages and salaries.”

This group has quickly become the “norm-setting class” for society, overhauling a system founded on the Protestant work ethic with one underpinned by “shared commitment to the creative spirit in all its many manifestations.” As such, the expectations of the Creative Class have reshaped workplace culture and lifestyle. To meet the Creatives’ demands for a challenging, flexible, and tolerant workplace, companies have adjusted by implementing “no collar” offices, malleable working schedules, and innovative management strategies. This free-flowing, bohemian ethos also characterizes the lifestyle of the Creative Class, which, Florida argues, is built on experimentation, active recreation, and artistic leisure activities.

Just as companies have adjusted to the demands of the Creative Class, places, especially cities, must do the same. Florida contends that cities or regions which successfully attract and retain creatives will thrive, while those that fail to do so will be left behind. Florida does not offer concrete recommendations for “building creative communities.” As a disciple of the eminent Jane Jacobs, Florida recognizes that creative communities “cannot be dictated in any top-down fashion,” but must grow organically in an open, tolerant environment.

Instead, he outlines a general strategy based upon the “3T’s of economic development” – technology, talent, and tolerance. He also emphasizes the importance of quality of place – or “territorial assets, the fourth T of development. Florida argues that “cities need a people climate as much as, and perhaps even more than, they need a business climate.” He points to Austin, Texas as an example of a city that has successfully employed the 3T’s and quality of place to attract Creatives. The city’s leadership was integral in attracting high-tech firms to the city, bolstering the nearby University of Texas, and investing in lifestyle amenities, including the local music scene. Consequently, Florida argues, Austin has become a hotbed for young Creatives.

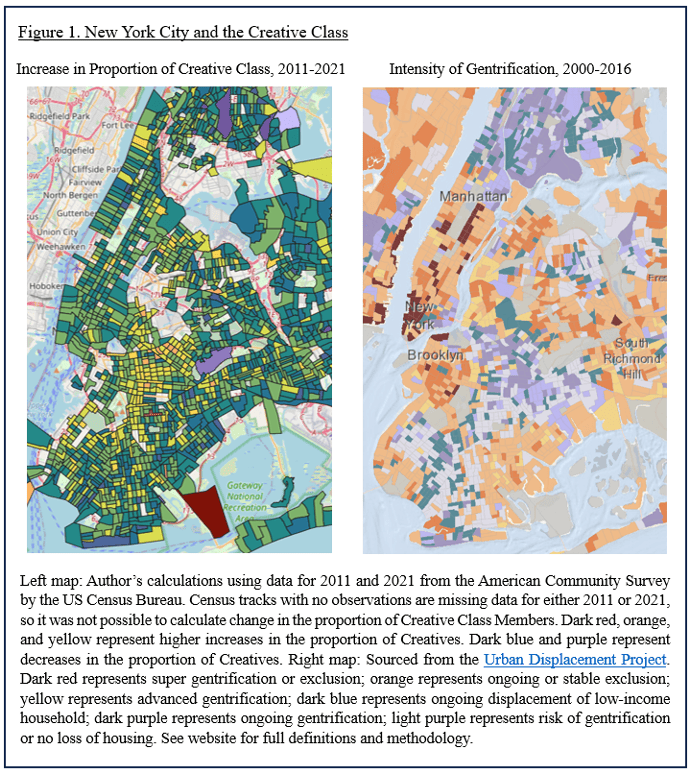

In an addendum to the original edition of the book, Florida also briefly acknowledges the challenges of inequality and class division associated with the rise of the Creative Class. He argues that some cities with a high concentration of creative professionals experience a phenomenon known as the “spatial sorting” effect. This effect occurs when highly skilled workers cluster in specific urban areas, leading to gentrification and rising costs of living in those neighborhoods. As a result, lower-income individuals and families may be priced out and face displacement, exacerbating inequality. He argues that, consequently, “social cohesion is eroding within our cities and countries, as well as across them.”

Critiques

The main message of the book is that in our modern world, creativity breeds competitive advantage and economic success; as such, cities should strive to attract and retain Creative workers. With this thesis, Florida does not offer anything particularly new or controversial. There is a broad, interdisciplinary consensus that creativity is essential for innovation and economic development. For centuries, economic theory has held that knowledge creation is key for improving skills, raising productivity, and driving long-run growth. There is also general agreement that cities play an essential role in incubating creativity and must compete to attract high-skilled workers. As urban economist Ed Glaeser points out, public intellectuals such as Adam Smith, Alfred Marshall, Jane Jacobs, and Paul Romer are “all about creativity, especially in urban areas.” Glaeser goes on to argue that it is not immediately evident that “there is a difference between the human capital theory of growth and [Florida’s] ‘creative capital’ theory of growth.”

Generally, talk Creative Class seems similarly contrived. The argument that the Creative Class truly constitutes a unique unit, worthy of a distinct ‘class’ label, is highly debatable. Florida writes that “social identities…cultural preferences, values, lifestyles, and consumption and buying habits,” all flow from the common economic function of Creatives as innovators. How much does the software engineer or derivatives analyst have in common with the fine artist trying to make ends meet by taking on an extra shift at the restaurant or the nurse technician working 14-hour shifts at the hospital? One need look no further than average wages to see clear discrepancies: the average base salary of a software engineer is 139,952 USD, while the average salary of a fine artist is less than half, at 53,082 USD. This is not to denigrate either occupation, it is only to suggest that lifestyle, preferences, consumption patterns, and identities are unlikely to be cohesive among members of the Creative Class. Tellingly, Florida himself admits that members of the Creative Class do not often identify as such.

Furthermore, by dividing society into the Creative Class and non-creatives, Florida discounts the importance of workers in complementary sectors and neglects the needs, concerns, and interests of marginalized communities. He dismissively notes that “more than eight in ten (80.9 percent) of Creative Class jobs are held by whites, who make up just 74 percent of the nation’s population.” He also points “soberly to the fact that the most creative places tend also to exhibit the most extensive forms of socio-economic inequality.” One critic compellingly argues that “as presently defined, the Creative Class [distinction] produces an explicit, reconfigured version of the old hierarchy between ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultures and serves to reproduce class distinctions.”

Although Florida briefly mentions issues of class division and inequality, it is a topic that deserves more attention throughout the book, particularly with respect to the issue of gentrification. In fact, maps of New York City show that neighborhoods that have seen a substantial increase in members of the Creative Class are the same that have experienced the most extreme gentrification and exclusion (see Figure 1). For example, soaring housing prices in Brooklyn, particularly in neighborhoods like Crown Heights, have pushed out a significant portion of the Black and West Indian populations who formerly resided in the area. When gentrification displaces and excludes residents, particularly those in marginalized or low-income groups, it can “dilute the authenticity and cultural and creative potential of vibrant neighborhoods.” To truly establish creative communities and cities, it is critical to mitigate gentrification through “inclusion-oriented policies – such as reforming zoning laws, enhancing urban transit, and enabling the development of affordable housing.”

The purpose of urban regeneration should be, first and foremost, to provide all residents with improved quality of living. Access to community spaces, cultural amenities, and parks should be the right of any urban dweller, not simply those in the Creative Class. The key to urban growth is not simply to establish “scenes” that attract bohemian knowledge workers; it is to make cities that work for people, regardless of occupation or income. This is seemingly lost in Florida’s insistence on attracting and retaining Creatives. Furthermore, his overemphasis on Creatives fails to acknowledge that creativity is not the exclusive commodity of the privileged few. Creativity is an innate human attribute, one which should be nurtured in every human being and valued over and above its capacity as an economic force. This approach necessitates a paradigm shift. Instead of asking how cities can appeal to Creatives, the question must be, how can the city itself become more conducive to the growth of creativity in all facets of society and dimensions of urban life?

An Alternative Approach

Building a creative city is by no means an easy task. City planners and government officials can only do so much to spark the growth of creativity, but they are certainly not helpless in their efforts. In fact, municipal governments have an essential role to play in creating niches where creativity can bubble up from the neighborhoods, communities, and groups that compose the city’s diverse social fabric. Often, it is the formal and informal neighborhood groups, associations, and clubs which truly nurture a city’s creative impulse, yet they receive hardly any mention in Florida’s book. These networks help strengthen a city’s social capital and enable creative experimentation in many aspects of urban life, from environmental movements to neighborhood development to community arts initiatives.

Efforts to support neighborhood associations and communities can simultaneously promote creativity and inclusivity, improving a city’s quality of place. For example, support for organizations like art coalitions, theater troupes, or historical preservation and heritage leagues allows locals to connect with their neighbors and promotes community vibrancy. Enabling and working alongside neighborhood associations can also foster creative approaches to development which open “new opportunities for those who are socially or economically excluded.” Creativity and inclusivity need not be isolated from one another. In fact, in a truly creative city, they are indistinguishable. Indeed, this is the creative city’s great strength: it facilitates interactions between diverse groups of people, giving life to new ideas and providing the necessary environment for those ideas to take root, grow, and blossom.