Human urbanization began around 7,000 BCE and will end in the lifetime of today’s children. The urban share of the global population will stabilize at about 75% in 2100. In this final phase of human urbanization India, for good or ill, will take a leading role. This blog asks how can India help ensure that its forthcoming urban boom contributes to national prosperity, employment, and economic dynamism? To help answer this question, we draw on culinary insights (pancakes), iconic construction from the ancient world (pyramids), from genteel wisdom (Jane Austen), and from less genteel wisdom (1980s-vintage slasher films).

When we think of a sprawling mega-city crowded with fetid slums, we are often drawn to images of India. The Nobel Prize-winning writer V.S.Naipaul referred to urban India as an Area of Darkness and again as a Wounded Civilization. In reality, India is not a country of cities or slums. India is still a country of farmers. In 2021 only 34% of the Indian population were estimated to live in urban areas. That isn’t much. It is less than Sub-Saharan Africa (42%) and way behind China (63%).

Our currently misguided preconceptions about India could become a reality. Get ready for India’s urban explosion. Between 2018 and 2050 the number of urban dwellers in India is forecast to increase by 461 million people. Along with Nigeria and China, India will account for almost 40% of global urbanization in these three decades.

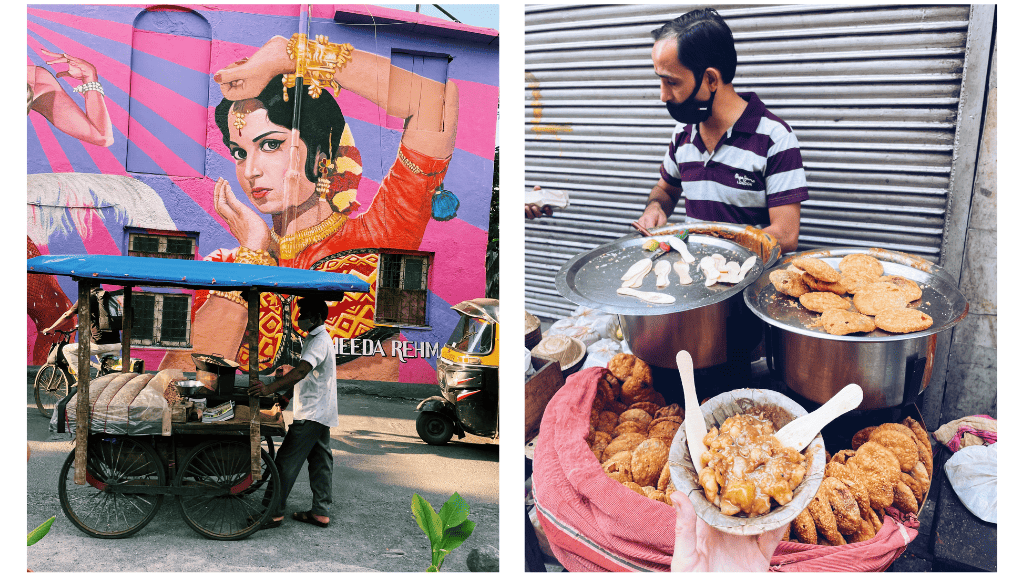

Contemporary urbanization in India is a pancake, sprawling outwards, crowded but at a low level, with poor transport and heavily congested roads. Much of the population squeeze into informal housing (slums) to be near jobs. More than 40% of the population of Mumbai lives in slums. These crowded slums generate an acute shortage of space within 10-15km of the center of Indian cities. To absorb this rapid influx of population cities in India need to transition into pyramids. Pyramid urbanization occurs when horizontal expansion is increasingly accompanied by infill development and building upwards in the urban core. This is not a call for building iconic skyscrapers, but those 5-10 story buildings that would allow a growing population to live more comfortably and to nurture productive economic activity that benefits from urban scale and agglomeration potential.

In November 2022 the findings of a World Bank report were widely discussed in India. To cope with this rising tide of urbanization, to transition from a pancake into a pyramid, India will need to invest $840 billion over the next 15 years ($55 billion p.a.) into urban infrastructure. Without this investment, the remorseless urbanization of India will create intolerable pressure on affordable housing, clean drinking water, reliable power supply, and free-flowing road transport.

If a country of farmers India has also long been a country of urban dynamism. India’s cities occupy 3% of the country’s land area but contribute 60% of the nation’s GDP. Urban growth has been responsible for 80% of recent declines in national poverty. Thinking of the coming urban boom…. across Africa the tight historical link between urbanization and economic growth broke down in the 1970s, could the same thing happen in India?

Another recent World Bank report – the title said it all – Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability – identified the key constraint holding India back from pyramid urbanization. India needs “efficient land tenure and ownership record systems”.

When households or businesses have a formal certificate of ownership, they can more easily (and profitably) sell out to a property developer who can acquire enough of those small parcels of land to build pyramids. The ability of a property developer to legally acquire land will in turn encourage banks to finance pyramid development. Once property is registered it can be more easily taxed to provide local government with the necessary revenues to build urban infrastructure. Recall the need for urban infrastructure? Well, between 2011 and 2018 urban property tax in India raised a mi sicule 0.15% of GDP in revenue.

Let us take a step back here. This is not a technical-India-specific legal reform. This discussion takes us to the heart of one of the (if not THE) big ideas in economic development. With apologies to Jane Austen,

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a dysfunctional economy in possession of low investment must be in want of good institutions.’

The World Bank’s focus on the formal tenure of property is no surprise. The prevailing orthodoxy in economics is that ‘good institutions’ (such as property rights) are crucial to promote investment-led, sustainable, and rapid economic growth. As Daren Acemoglu and others put it in a 2004 article ‘Institutions as the Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth’. Institutions were the focus of the influential 2012 book by Daren Acemoglu and James Robinson. The book makes the big global-historical claim that institutions explain ‘Why Nations Fail’ and ‘The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty’. The economic historian Douglas North (work for which he won the Nobel Memorial Prize in economics) declared that “the heart of development policy must be the creation of policies that will create and enforce efficient property rights.”

There is plenty of evidence. There are statistics. A quantitative measure of institutions is closely related to economic growth across 127 countries. There is history. Until 1945 South and North Korea had similar histories, resources, culture, and geography but ended up with very different institutions, the crucial one, being the abolition of private property rights in North Korea. By the end of the 1990s South Korea was a newly installed member of the global club of rich countries – the OECD – and impoverished North Korea was suffering from periodic famines.

But aren’t property rights and urban development all about big corporations, sweeping away slum dwellers to build sparkling malls, middle-class housing, and office blocks?

Or maybe not…?

Hernando De Soto famously and influentially placed the creation of property rights for the poorest at the center of his thinking on development. Without property rights, the informal slum dwellings and market stalls of the poor are ‘Dead Capital’. With property rights, the poor can use their newly created formal assets as collateral to borrow money to invest. Property rights give them an incentive to do so – why turn a shack into a house if it may be bulldozed without compensation to build a road? Slum dwellers in India crowd into fetid, insanitary, slums to access urban jobs and schooling. With the creation, registration, and protection of property rights existing slum dwellers will have much of the capital to build better housing for themselves. Offering their labor from the geographical heart of India’s urban boom those slum dwellers will have the longer-term urban wage incomes to be the market for the purchase or rental of those five-to-ten-story buildings, the modest pyramid urban development that India needs.

Three cheers then for the World Bank. A modest, technocratic intervention (property rights) will empower urban India from the bottom-up (slum dwellers) and top-down (banks and property developers). India can transition from pancake to pyramid urbanization. India will leverage the ongoing urban boom in India to the cause of creating create good jobs, productivity, and economic dynamism….

Or maybe not….?

I mentioned Jane Austen a little while ago so it seems entirely appropriate and in-theme to start discussing slasher films. Aged 14, growing up in rural England, I had access to a video rental shop with less age-based discernment than that doyen of 1980s respectability ‘Blockbusters’. My friends and I, ever avid to scare ourselves into wide-eyed, open-mouthed silence, hired slasher films – Halloween, The Hills Have Eyes, Friday the 13th…… If you had a similarly critically-impaired youth you will know how slasher films end. Once the nubile heroine turns her back on the supposed dead body of the masked villain, the music turns scary, he opens his eyes, sits up, and resumes his bloody rampage.

We have celebrated the transformative power of property rights in urban India. Solution found we have turned our backs on the technocratic question of property rights and started thinking about the myriad other problems of urban India. Property rights are not finished, they are about to rear up and resume their critical rampage through urban studies.

To be continued…..