We began Part I with a dramatic backdrop.

The End of Human Urbanization!

Can we pause for a moment for a confession?

I confess! I started the blog that way to get your attention. I was told to do this by a power-point wielding expert on blog writing. I am not referring to a climate-change induced environmental catastrophe, a zombie apocalypse, or Donald Trump becoming President for Life. My meaning of ‘end’ is more prosaic than that.

People first moved into cities around 7,000BCE. The process of urbanization will come to an end in the lifetime of todays’ children. I don’t mean END!!! I mean end in the sense that urbanization as a dynamic process by which millions move from rural to urban areas will be complete. The urban share of the global population will stabilize at about 75% by 2100.

In these two blogs we focus on the central role of India in twenty-first century global urbanization. Between 2018 and 2050 the urban population of India is forecast to increase by more than 460 million people (or by more than three times the total population of Russia today). We ask, can India leverage urbanization to promote economic dynamism, prosperity and poverty reduction? Will India instead succumb to a growing reality of dysfunctional urbanization and slide into the Africa urban-trap. Since the 1970s the link between urbanization and economic growth has broken down in Africa. The key is whether India can shift from a pancake model of urbanization (a low-level sprawl) to a pyramid model (building upwards).

The 1978 film directed by John Carpenter – Halloween – sees iconic horror-villain Michael Myers returning to his hometown 15 years after murdering his sister. Michael escapes from a mental hospital (Sanitarium) and returns home to complete his family-downsizing project. Michael spends much of the film lumbering knife in hand behind nubile scream-queen Jamie Lee Curtis (the second sister, named Laurie Strode). The physics represents a fascinating paradox, why does the running heroine never outdistance the walking villain? Towards the end of the film Laurie stabs Michael in the neck with a knitting needle, then turns her back assuming him dead…Michael duly opens his eyes, rises and resumes his bloody rampage.

Slasher films never END. A slasher film only ever pauses.

More end…

Than END.

In true slasher film tradition, I also present to you a sequel, after careful thought and consultation with expensive brand consultants I have called this ‘Part II’. In Part I we lauded the focus of the World Bank on creating, registering, and protecting urban property rights in India. We found evidence that this would help leverage the coming urban boom in India to promote an inclusive form of pyramid urbanization. In light of slasher film wisdom, don’t turn your back on property rights satisfied that the problem has been solved and turn your attention instead to the myriad other problems of urban India. Learn from Laurie Strode. This is Part II. Property rights are not dead, they are about to rear up and resume their critical rampage through urban studies.

India has a total population of 1.4 billion people, squeezed into a relatively small landmass. This gives India a population density of 434 people per square kilometer (compared to 36 in the US). India currently has a low urban share of the population (34%). So nearly two-thirds of the population are still living and working in rural areas – well-dispersed across the entire country. Land is also subject to overlapping claims. When a property owner dies an unclear and expansive roster of (grieving) relatives acquire legal rights of inheritance.

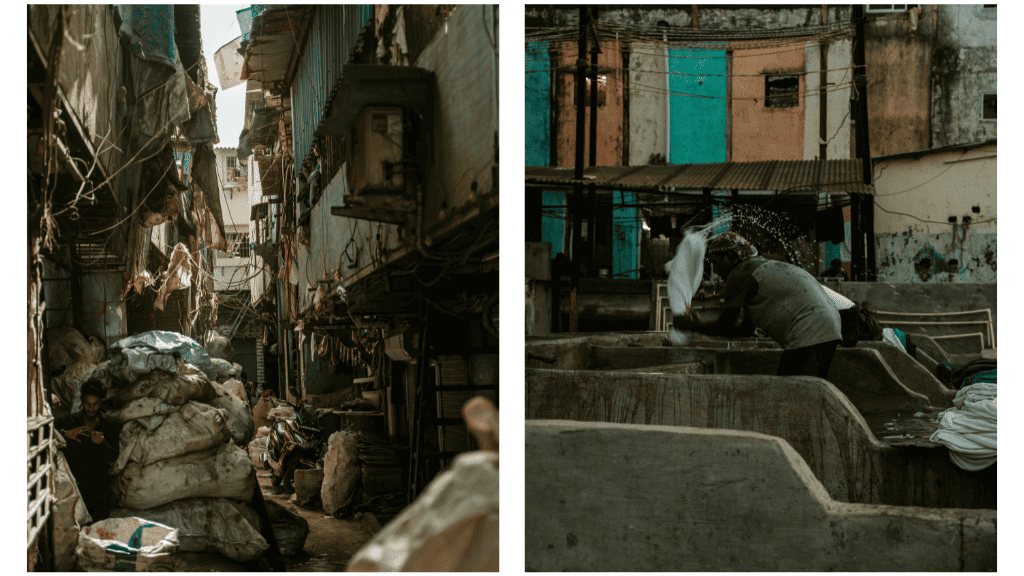

Population growth, rapid rural to urban migration, and overlapping property claims have fragmented property ownership. Between 1990–91 and 2000–01, the number of operational farm holdings increased from 106.64 million to 119.93 million and the operational farm size declined from 1.57 hectares to 1.33 hectares. Between 1984 and 2010 the average floor space per person in Mumbai remained stuck at 4.5 square meters. By comparison in Shanghai, China it increased from 3.65 to 34 square meters.

This fragmented land needs to be pooled in India, to build urban infrastructure and housing. That fragmentation exacerbate a market failure associated with any efforts to pool land. Once a buyer commits to buying certain plots, the value of subsequent plots nearby will increase. The owner of a single tiny plot could potentially have veto power over the entire project by holding out for a higher price. The fragmented nature of ownership means that there are potentially thousands of such veto points. There are also laws protecting the rights of tenants who are renting land or buildings – those veto points are well-protected. In Mumbai for example, strict rent controls originating a century ago, have since evolved into a system of low and tightly controlled rents, tenants that can only be removed on highly restricted grounds, and tenancy that can be inherited.

There is a famous example of how fragmented land ownership has stalled industrialization in India. In May 2006 the Chief Minister of West Bengal (a state of 90 million people in eastern India) announced that the state was the favored destination for the Tata Nano project. The project aimed to produce a $2000 car for the Indian mass market. The factory was due to be built on 1,000 acres identified by the state-run West Bengal Industrial Development Corporation (WBIDC). The fragmentation of ownership meant this was estimated to affect the land rights of 12,000 owners.

NB. The author moved house a few years back. See his recent blog about where he lives. Shameless plug I admit. The move necessitated the sale of his existing flat to one person and the purchase of a house from one person. The process took several months and was very stressful. With morbid enthusiasm the UK insurance company Legal&General proclaim that moving house is more stressful than having a child. Somewhat exaggerated according to close examination of the relevant evidence and perhaps related to the fact that Legal&General kindly offer home ownership insurance but don’t offer assistance (financial or otherwise) related to child conception. But, back to my main point. My limited foray into the property market was stressful. Imagine buying property from 12,000 people simultaneously? I don’t often feel sorry for large multinational companies. I might make an exception here.

A recap…..with fragmented land holdings there is a profound market failure associated with the operation of a free market. Once the buyer commits to buying some plots, the value of subsequent plots will increase. A single tiny plot could eventually offer its owner veto power over the entire project.

This problem has been overcome by the use of ‘eminent domain’ intervention by the state where the purchase prices can be established by reference to existing market prices and the land then subject to a compulsory state-backed purchase order. This is what I meant by the blog-title, that building a city can require property rights to be weakened.

In India formal powers of compulsory acquisition were established by the Land Acquisition Act of 1894 which utilized the concept of ‘eminent domain’. The Act enabled the state to make compulsory purchase of private assets for public purposes with compensation linked to market prices. This law was re-incarnated as the 2005 Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Act that set a framework for state governments to acquire land for industrial estates.

After being launched many SEZs then stalled in response to massive political protest, these included the Salim Group’s Petro-chemical SEZ in Nandigram, West Bengal, the Reliance Group Multi-purpose SEZ near Mumbai, and the $12 billion POSCO steel SEZ in Orissa. A 2021 press release issued by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry indicated that of the 425 SEZ-s by then approved, only 265 were operational, many of the remainder moribund in face of political protest.

A key political spark igniting this anger were the prices being paid for land, which generated a sense of injustice. In India land often lacks a clear market price. The official recorded value of land payments is often suppressed to avoid payment of stamp duty. In many regions there are only few transactions and they are not well documented, giving room for officials to manipulate the compulsory purchase prices. There is also likely to be a vast difference between the current value of land used in subsistence agriculture (the selling price) and its future value once converted to urban use (the ultimate profit to the developer). In the case of the Mahindra World City Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Jaipur, Rajasthan, Mahindra paid the state government US$22,679 per acre, the land cost about $66,000 per acre to develop, and long-term leases for the developed land were sold to companies for $223,000 per acre and for residential plots at US$554,000 per acre.

Those losing rural land in India are unlikely to ever benefit from the resulting urban-industrial development. At the Mahindra World City SEZ in Jaipur, Rajasthan the only jobs in the SEZ that local people could aspire to were a few badly-paid, insecure jobs as gardeners, drivers, guards or cleaners. While the firms entering the SEZ (Infosys/ Deutsche Bank) required skilled and English-speaking labor, only 56% of the (local) inhabitants were literate.

As the use of eminent domain was beaten back by angry mass mobilization, in response the government of India passed the 2013 Land Acquisition Bill. To reduce the sense of social injustice ‘Public Purpose’ was more clearly defined. Eminent domain and compulsory purchase could be used to acquire land for public hospitals, water conservation projects, or affordable housing but not (as previously) luxury housing, golf courses, and swimming pools.

When land is acquired for setting up private companies (rather than public purpose), the consent of at least 80% (or 70% in the case of a public-private partnership) of the affected families is now mandatory. The new Act also provided for generous resettlement and transportation allowances for those losing livelihoods. The intended beneficiaries were not just land-owners but also tenants, sharecroppers and agricultural laborer’s who worked on the acquired property. There were 12,000 landowners to compensate for the Tata Nano project. The new Act has added an arduous process of consultation and even more compensation – to those working on the affected land.

And so, we near the end of the sequel or Part II as I like to call it. Part I concluded with the suggestion that the creation, registration, and protection of property rights in urban India would help cities make the transition from pancake to pyramid patterns of development. The problems of urbanization in India looked solved by clever, technical, World Bank thinking. The villain wasn’t slain but reared his ugly head in Part II. Strengthening property rights in a context of dense population, fragmented property ownership and legal protection of property owners exacerbates a market failure. The use of eminent domain – or weakening property rights – is a globally common solution to this problem. In India, an intense and mobilizational democracy generated a massive political opposition to the use of eminent domain in the 2000s. The political solution – the 2013 Land Acquisition Act – created the political safeguards of consultation, consent, and compensation. These safeguards in turn rendered the time and cost of acquiring land a hopeless business proposition across much of urban and rural India.

As we close Part II India looks slightly more likely to slide into Africa-style dysfunctional rather than an inclusive pyramid model of urbanization.

Is this the end of the story? Will the villain be back for Part III?

To be continued….possibly….