Book Review

The Dragon from the Mountains by Matthew McCartney

My CCI colleague Matthew McCartney joined us in 2021, welcoming him with a CCI launch event for his excellent book, The Dragon from the Mountains: The CPEC from Kashgar to Gwadar. In it, Matthew comprehensively evaluates the promise of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a series of concentrated investments in energy and transport infrastructure, as well as in special economic zones, designed to deepen economic ties between Pakistan and Western China as a flagship component of the Belt and Road Initiative. Matthew ultimately concludes that while the CPEC will not be the game-changing ignition of a Pakistani economic miracle (and that those claiming this may actually be doing more harm than good), it is likely to have some positive economic effects and unlikely to transform Pakistan into a subservient Chinese client state. Three years later, it’s worth a brief revisit to The Dragon from the Mountains amid the economic and geopolitical tumult of the past several years.

In general, there is little fault to be found with Matthew’s historical context, empirical evidence, and subsequent conclusions about CPEC. We should expect modest gains in investment, productivity, and the like, without expecting miracles. While it is quite large for an infrastructure program, valued at over $60 billion, Pakistan is itself a high-population middle-income country and these effects will be somewhat dispersed. CPEC for a much smaller, poorer country (Matthew offers the example of Laos) would have a more substantial and immediate effect on growth.

There is an important undercurrent which runs through each of the major topics Matthew analyzes (big infrastructure projects, economic spillovers, special economic zones, trade policy, and industrial policy), that the effectiveness or lack thereof regarding any of these domains is at least partially a function of governance, or of institutional quality. More specifically, the notion of “good enough governance” comes to mind.

Pakistan doesn’t need to become Singapore overnight to achieve higher, faster, and more consistent growth. But to achieve a real development breakthrough, the status quo is untenable. In the chapter on industrial policy, Matthew documents various metrics by which governance in Pakistan is so poor. Pakistan regressed from 77th in 2009 to 136th in 2019 on the Doing Business Index, failing to improve its score for a single criteria. Other measures documented, such as the World Economic Forum’s competitiveness measures, the Corruption Perceptions Index, and various rule of law indices, all either show decline, stagnation, or deep underperformance compared with regional peer countries.

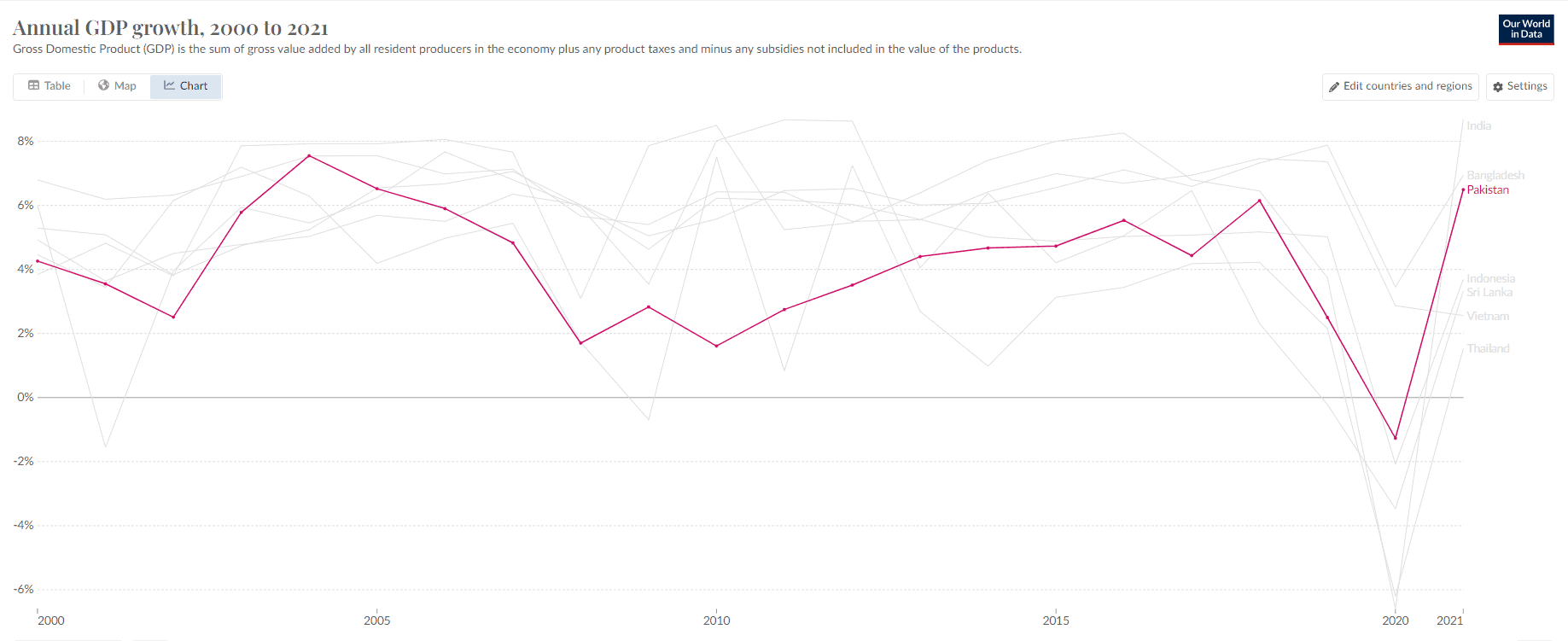

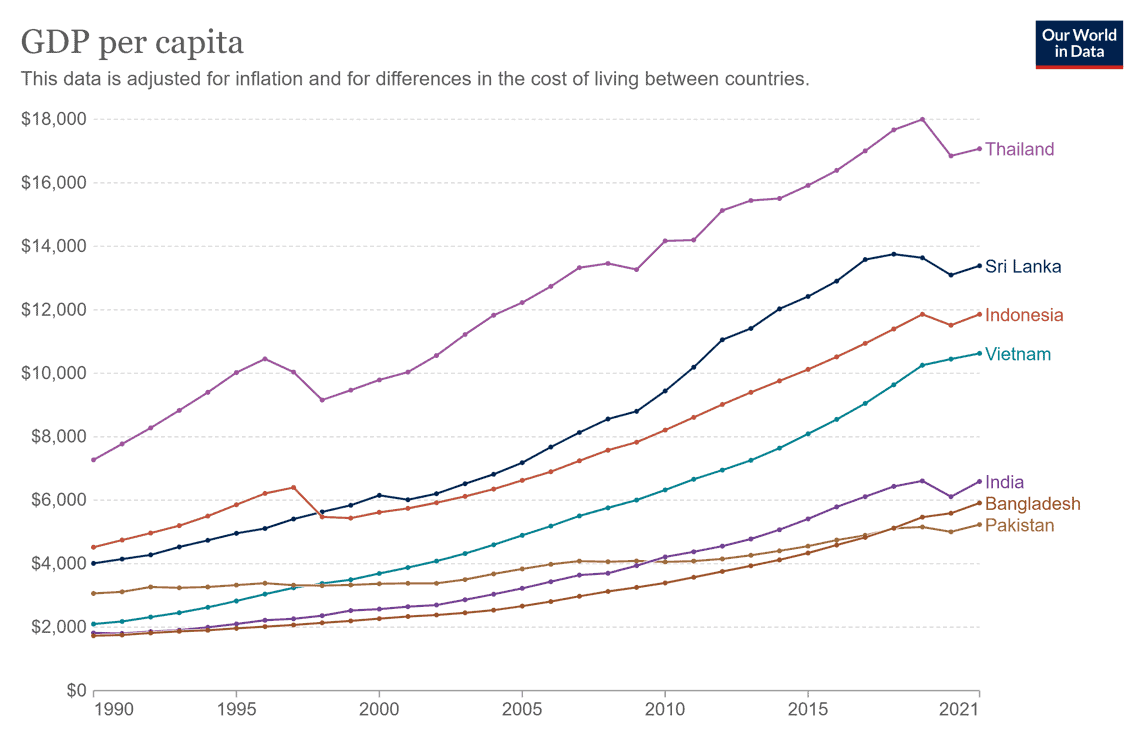

Among those regional competitors (India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, Bangladesh), Pakistan consistently has one of the lowest, if not the lowest, annual growth rate (to be fair, however, Pakistan has maintained 4-5% growth for decades, while avoiding any major negative growth episodes). But even among high performers of this group, governance was not “perfect.” It was good enough such that, over the past approximately four decades, Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam have broken away from the bottom three. For decades, GDP per capita was still higher in Pakistan than both India and Bangladesh. No more.

Grindle (2007) coined the concept of “good enough governance”, pushing back on the “good governance” agenda advocated by the development community as an important precursor for growth. Rather than needing good governance across the whole suite of rule-setting institutions, decision-making structures, administration and service delivery, government staffing, and so on, growth was achievable without solving all of these challenges at once, in their entirety. As Pritchett, Woolcock, and Andrews (2012) note (see footnote 14 for a full accounting), a suite of similar ideas (“second-best institutions”, “good struggles”, “just enough governance”) later emerged offering similar critiques of good governance, aimed at a more realistic and productive reform agenda.

More recently, McDonnell’s (2020) “pockets of effectiveness” has shown that highly effective units can be developed and maintained within an otherwise dysfunctional state. Perhaps most relevant for Pakistan are Yuen Yuen Ang’s (2016, 2020) groundbreaking analyses of China’s recent economic miracle. Ang documents the importance of both directed and bottom up innovation in governance, as well as the ways in which certain types of corruption ultimately helped to develop Chinese markets. China did not follow the prototypical “good governance first” agenda, yet it achieved remarkable success. Despite significant resource expenditure, creating good governance in most places remains elusive.

As a rule of thumb and default heuristic, the “good governance” agenda is preferable to many of the alternative possibilities–those that are likely to be realized on the ground, not necessarily those of economists and political scientists. Like the much-derided (but actually effective) Washington Consensus (Grier and Grier, 2021), you could easily do far more damage and many countries ultimately continue to do so. But the lessons from Ang, McDonnell, and others above suggest that a more effective, productive Pakistani state and institutions are in theory achievable. And past growth episodes in Pakistan go beyond theory, telling us that this is indeed possible.

Whether that change can be assisted by external actors or if it must come solely from within Pakistan is an open question. Matthew is the person to ask what it might take to chart such a path forward for Pakistan that is politically feasible, if at all. As a complete outsider, Pakistani political dynamics strike me as especially complex and difficult for a would-be reform effort to successfully navigate (especially given the outsized political role of the Pakistani army). For instance, two of Pakistan’s major political parties (themselves bitter rivals and therefore unstable coalition partners) just formed a governing coalition to keep imprisoned former Prime Minister Imran Khan out of power despite his party winning the most seats–certainly a difficult moment to try and get good, or even just good enough, governance-focused reforms through.

But this point strikes at the heart of why Matthew’s conclusion in The Dragon from the Mountains could only be that while CPEC will likely have a modestly positive economic impact, it could never be transformative. Pakistan is not being held back from higher, faster growth by a lack of power plants, rail networks, and ports. Pakistan’s economic performance is not being held back by a lack of good governance. Pakistan has enjoyed episodes of sustained growth in the past, it can be achieved again. Pakistan needs good enough governance. It is with good enough governance that Pakistan’s advantages, like its strategic location and widespread use of English, or a massive investment program like CPEC, can actually be leveraged into long-run economic transformation.