I recently gave ten one-hour lectures at the University of Zambia (UNZA) in bountiful summer-ripe Lusaka.

The lecture series was planned in collaboration with the Center for Urban Planning and Research (CURP) in the Department of Geography. I want to thank Ms Dorothy Ndhlovu (CURP) and Dr Gilbert Siame (Geography) for facilitating these lectures. Also, thanks to the Acting Dean, Dr Musundu, and the Acting Head of Geography Dr Chisolo, who formally hosted the lectures and for their generosity in welcoming us and presiding over the closing ceremony.

As an economist working for a think tank of city enthusiasts, the topic of the lecture course was never in doubt. We quickly agreed on a bold title, ‘Rethinking African Cities,’ Though we debated at length the appropriate list of sub-titles including ‘Inclusivity, Governance, Poverty, and Innovation,’ among various others. At some point, we all lost track, and every subsequent mention of the course included a different combination of sub-titles. We like to think this showcased a vibrant, dynamic, and flexible course.

I landed in Lusaka on the 16th September. The new (Chinese-built) Kenneth Kaunda international airport was a model of friendly and sparkling efficiency. It took five minutes to get a business visa. A ruminative nod of appreciation, not any re-thinking, was needed regarding this splendid showcase of urban infrastructure.

Leaving the airport, I was reminded of the time, two-and-a-half years ago, I emerged, blinking into the sunlight, from twenty-five years of captivity as an academic development economist, into an interview for a city-oriented thinktank. A tiny practical problem with my undoubted enthusiasm was that in those twenty-five years, I don’t recall ever having uttered the word ‘city’. Well, ok that is not strictly true. There were occasional Saturdays. My friend Ashwin would ask, ‘Who are Liverpool playing today?’, and twice a year I would reply, ‘Manchester City, I think’. I meant ‘never uttered’ in a non-footballing-academic sense. Economists, even development economists, don’t talk often about cities; we rarely talk about the importance of real, physical space. We talk about everything that city people discuss – governance, institutions, land acquisition, industrialization, structural change, rural to urban migration, transport infrastructure…but we stop short at bringing all these concepts together under the unifying umbrella of ‘city’.

I smiled during the interview and talked about a mutual journey of discovery and of ‘city’ being a unifying umbrella. Perhaps there weren’t many other candidates?

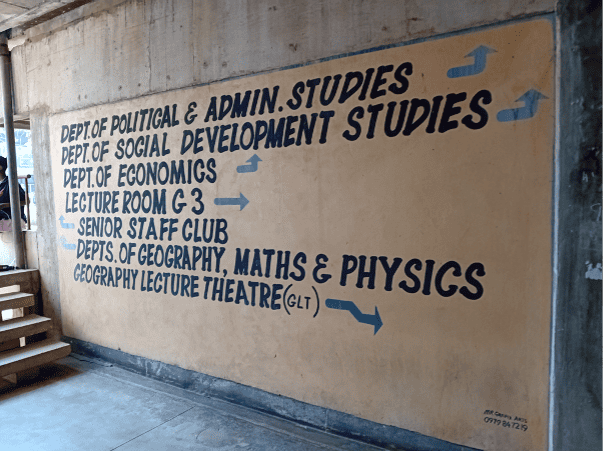

In Lusaka on Monday afternoon, I crossed the Great East Road and entered the north gate of UNZA Main Campus. I noticed that UNZA provides a useful corrective. The photo below shows that geography is the metaphorical foundation of all the social science. Knowing economists as I do, they will probably look at the same photo and suggest that they are closer to heaven.

As a recovering economist, I wanted to offer a course (that avoided lazy stereotypes, except when lazy was compatible with statistical evidence) that welcomed the usual suspects – urban planners, city councils, and local government workers – but also explained to officials from the Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank, why economists should think about cities. I wanted to emulate President Obama’s glorious hand gestures and say to newly enlightened economists,

When LUSAKA works, ZAMBIA works!

The good looks, charismatic stare, stylish shirt, and ecstatic audience remain works in progress.

My big message across the ten lectures was that the form, function, and nature of urbanization in Lusaka, and also Ndola, Kitwe, and the other towns and cities of Zambia has a profound impact on the big issues that big economics ministries think about – economic growth, employment, industrialization, and exports. Zambia cannot fulfill its oft-stated vision of diversifying the economy away from copper until it promotes a more productive form of urbanization. The vision was ready. The hand gestures had been carefully rehearsed.

We forgot one thing.

We never thought to check….

The course date overlapped with the Zambian national budget. Our invite to the Ministry of Finance was akin to telling Father Christmas (Santa Claus for my American friends) to pop around for a ‘coffee, cake and gossip’ on Christmas Eve should he has a spare moment in the midst of delivering gifts to the 2,397,435,502 children that UNICEF estimated required them in 2023.

The Ministry of Finance sent their polite regrets.

Nonetheless, we did have a great turnout. We welcomed officials, officers, and members of the Policy Monitoring and Research Centre (PMRC), Ministry of Local Governance and Regional Development (MLGRD), Lusaka City Council (LCC), Zambia Institute of Planners (ZIP), Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection (JCTR), Zambia College of the Built Environment, Southern African Institute for Policy and Research (SAIPAR), and the Department of Resettlements. I was delighted with the invite roster, but I confess, it made me a little bit nervous.

Most of my professional life, I have been teaching university students. When I step up to the lecture podium, I know what the students know. We select those we want to teach through a rigorous admissions process. Students need a certain grade in mathematics for admission to an economics course; they need particular undergraduate qualifications for a master’s program. This was different. I stood up in front of a room full of civil servants, think tank researchers, and professionals, not a relatively homogenous class of carefully culled applicants. And these were busy people, they were arriving after a full day at the office for a 4pm to 6:30pm class. Listening to other people talk for a long-time, even replete with Obama-style hand gestures and (less) charismatic stares, is hard work, especially once the habits of university life have long passed. The course was free, it wasn’t assessed. There were no angry parents, watching their bank accounts being emptied by avaricious UK teaching and living expenses demanding good grades and dedicated attendance.

We planned the course as a traditional university teaching module. We are in discussion with UNZA about turning the course into a regular part of their MSc in Spatial Planning. The format was scheduled to be two one-hour lectures and thirty minutes of questions a day. This format was about imparting knowledge, building capacity, and equipping policymakers to improve public policy. The course was informed by the approach found in a spate of recent ‘Big Policy’ papers that I had been reading.

These Big Policy papers were Lall et al (2021), written for the World Bank, which contrasts two forms of urbanization, ‘Pancakes to Pyramids: City Form to Promote Sustainable Growth’. The second paper was published by the OECD (2015) and entitled ‘The Metropolitan Century: Understanding Urbanization and its Consequences’. The third was published by UN-Habitat (2014) and entitled ‘Urban Planning for City Leaders’. The fourth, ‘Africa’s Cities: Opening Doors to the World’ was published by the World Bank (2017) and written by a noted World Bank scholar (Somik Lall) and two of the world’s leading urban-economics academics (Vernon Henderson and Anthony Venables).

These big policy papers are intended to influence policy-making by organizations (The World Bank, UN-Habitat, and OECD) that have the reach, credibility, and acknowledged expertise to have a real impact on the policy agenda. The goal of the reports was not to inform an academic debate but to enlighten policymakers in the global south about the potential of and the policy reforms necessary to achieve good urbanization.

In our letter of invitation to potential participants, we had made bold promises:

“Participants will gain valuable insights into the complexities surrounding urbanization in Africa and will be equipped with the knowledge necessary to actively engage in ongoing debates concerning the final wave of human urbanization in the twenty-first century. In addition, the course will foster dialogue, critical thinking, research collaborations, and transformative action aimed at addressing urban challenges across Africa and building sustainable, thriving cities.”

I made sure the course reflected the academic origins of the course conductor – that students would be able to “engage in ongoing debates”. I tried to keep the academic flame alight, the academic flag fluttering, and the third analogy equally pertinent. I presented proposed policy solutions as being a function of contested debates. I made it clear, for example, that urban planning solutions that work well in Kigali (Rwanda) do not work well in Kampala (Uganda), the importance of place being evident to geographers but much less so to many economists. With these minor academic variations, the course was a reflection of those big policy papers, and we intended to build capacity by imparting knowledge.

The format of two hour-long lectures and 30 minutes of questions was quickly dispensed with. The students were evidently not really ‘students.’ They soon settled into a groove of being participants in an extended discussion, which ran through the entire class and wasn’t ring-fenced in the last half hour. The eclectic mix of participants had been well-chosen. We had a fascinating and diverse mix of lived experience in the practice of urban planning and urban policy making.

In the lecture, ‘The Governance of Cities: Government Capacity (Kampala and Kigali)’ we discussed the idea that ‘capacity’ is about more than just skills and knowledge – the gap that is filled by the Big Policy Papers or a policy-oriented lecture course. Capacity, I proposed, IS about having a skilled bureaucracy, but it is ALSO about having a visionary political leadership with the drive to promote rapid economic development, a bureaucracy that has day-to-day independence from politicians and the ability to implement long-term economic reform, and a state with independence from groups less concerned with industrialisation and exports, like teachers and farmers. There was widespread agreement with this, discussion replete with practical examples of how the exercise of technical skills had been thwarted by political and administrative constraints.

In the lecture ‘Reforming Contemporary African Cities’ the contours of this debate really shone through. We were discussing the importance of land titling – giving land and property owners formal titles to protect them from eviction by property developers – to incentivise them to upgrade their residence or business, to give them collateral against which to borrow and invest, and to make the process of selling assets easier, whether for others to build factories, infrastructure, or bigger housing blocks. Participating in the discussion were civil servants who had led the recent Zambian effort to increase land titling. Zambia charged $100 a plot and left 95% of land un-titled; Rwanda by comparison, charged $6 a plot and registered more than 10 million plots of land. The practitioners spoke of the reluctance of many property owners to participate because they feared the title was a precursor to taxation, of hesitancy to implement the reform by local governments because the land tax on the titled property went to central government, and because of constant political interference.

The lectures provided a framework for discussion, some wider comparative studies, and some academic nuance. My more general experience was that I was introducing topics that were well understood by those practitioners present and I was providing them a platform to share their experiences. My takeaway from the lecture course was of well-experienced, well-qualified, and reflective civil servants who were unable to exercise their full panoply of skills because of capacity constraints in a much wider sense.

At some point we had discussed capacity building at UNZA. A tentative investigation revealed that UNZA had an abundant endowment of expertise and related skills. UNZA is the best public University in Zambia and one of the best in the Southern African region, ranking 501-600th in the Times Higher Education League Table (by comparison, the entirety of India has only around six Universities that rank above UNZA). The university Strategic Plan for 2018-2022 reveals that UNZA has no problem in attracting and retaining highly qualified staff. The university has around 880 lecturers and loses only 0.5% of them every year to other jobs. A brief survey of junior staff in UNZA (‘lecturers’) shows that almost all have PhDs, and many have MSc or PhDs from well-reputed foreign universities in Sweden, UK, Netherlands, US, China, and South Africa. However, UNZA faces problems in building a research environment, especially for younger staff. According to the Strategic Plan 2018-2022, “there is no mentoring and coaching programme for young lecturers; there are no induction programmes for teaching staff; and there is no exposure to new teaching methodologies and new knowledge, a situation which is affecting the delivery of lectures and quality of trained professionals.” Like the panoply of urban policy making, UNZA has ample skills but lacks the capacity to utilize those skills.

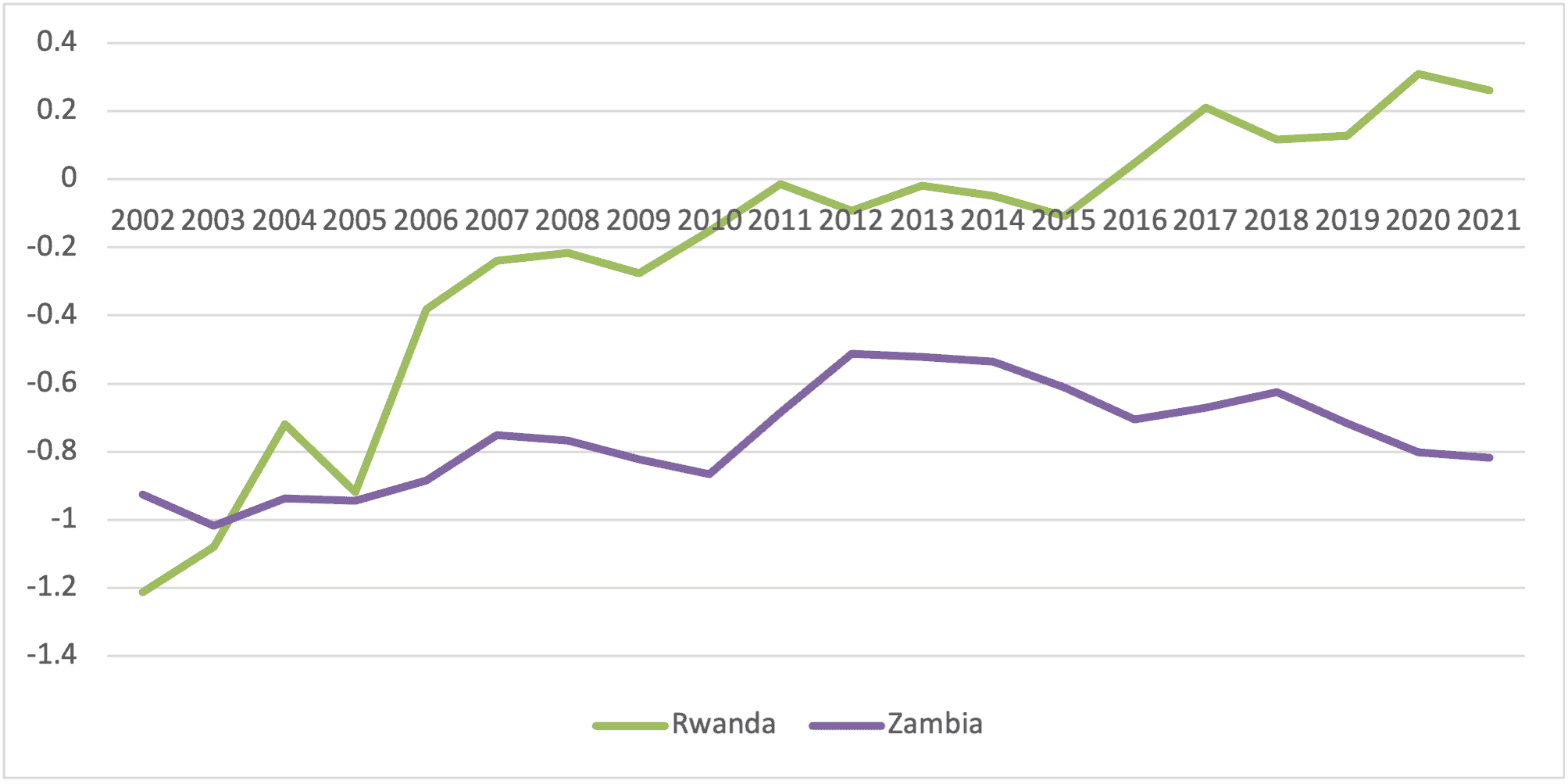

The blithe suggestions from the ‘big’ policy papers about the need to provide detailed policy advice fail to recognize the deep problem of building capacity in practice. One study identified 615 donor projects in Zambia related to civil service reform in the forty years after 1981. These efforts have not contributed to improved governance. The ‘Government Effectiveness’ indicator published by the World Bank captures perceptions of the quality of public services, of civil service and its degree of independence from political pressures, of policy formulation and implementation, and of the government’s commitment to such policies. The estimates in Figure 1 give Zambia and Rwanda’s scores, ranging from -2.5 to 2.5. Figure 1 reveals the stagnation or decline in measures of governance in Zambia and the steady increase in Rwanda. This stagnation occurred despite the strong emphasis on civil service reform in Zambia, as already noted, by numerous donors, including the World Bank and the IMF.

The enduring inability to expand the administrative capability of the state to implement effective policies has been called a ‘capability trap’ by Lant Pritchett among others. Based on current trends from the Index of Government Effectiveness (Figure 1), it will take Zambia, Senegal, Nigeria, and Tanzania almost 400 years to reach the current level of state capacity in Singapore (Pritchett et al., 2013:13).

Despite the concerns I noted earlier, I enjoyed ‘teaching’ this course immensely. It was a very different experience from the reading-intensive experience of university life. This course was structured around shared experiences of ‘doing urban policy’. My initial, rather naïve thoughts that this course was about capacity building, in the narrow sense of imparting skills and knowledge, evolved into something more rewarding. The participants did learn new skills, particularly in familiarization with recent academic work and development of a comparative urban perspective, which may not be available to busy Zambia-focused policy professionals. However, new skills were a small part of this experience. Capacity is about bureaucratic autonomy, the relation of the bureaucracy with politicians and with the wider society. Capacity is only in small part a technocratic issue of skills and policy advice. Capacity is ultimately a political question.

I came to Zambia as an economist who was learning to use the word ‘city’. I left Zambia realizing that good urban policy may be crafted by good economics, but can only be implemented by good politics.