It is a common enough refrain, that sometime between 1800 and 1851 London became the worlds’ greatest city. James Hamilton in his 2008 book London Lights argues that by 1851 London had become the “undisputed capital of the world”. Peter Hall in his 1998 book Cities in Civilization: Culture, Innovation and Urban Order was even bolder, claiming that, “sometime shortly after 1800, London had become indisputably the greatest city that had ever existed in the world.” This luminescence argues many others contained a darkness within or was founded upon a darkness without. The darkness within was the urban squalor, poverty, and deprivation of London, sometimes described as Dickensian after the great chronicler of nineteenth-century London, novelist Charles Dickens. The darkness without was the exploitative British colonial history that had drained wealth and resources from around the globe to build the glories of London. Radical economists such as Andre Gunner Frank have labelled this latter process “the development of under-development”, whereby economic growth in one country or region or city is a consequence of poverty and deprivation elsewhere.

This blog notes, but doesn’t critically engage with these big ideas and instead reflects more deeply on another idea. While much contemporary debate and media focuses on how the empire influenced London, this blog asks instead, how did the city of London influence the world? This blog answers this question by studying a lingering lunch that rolled into a late-night dinner that took place on the 28th December 1817 at 22 Lisson Grove in North London. A dinner that was soon after deliciously and dramatically designated,

A different font and font size, with capitals AND italics are scarce enough to render the significance of THAT evening.

The Immortal Dinner was hosted by 1817 artist-celebrity, Benjamin Robert Haydon who is now no longer mentioned even in books about art; his memory still lingers among some for his writing, particularly his voluminous diaries. His guests included poets of enduring fame, including John Keats and William Wordsworth, as well as poet and essayist of diminished fame but enduring critical regard, such as Charles Lamb, and a tail of the convivial but justifiably un-famous: Tom Monkhouse (a relative by marriage of Wordsworth); John Landseer (a landscape engraver); John Kingston (influential in the government stamp administration and absent even from the depths of Wikipedia); and Joseph Ritchie (whose biography gives the faint praise of being an explorer of Africa who “made no new discoveries”).

So, we ask here, if not themselves engaged in cerebral contemplation, how did the convivial consumption of roast beef and claret, and the conversations, networking, learning, argument, intoxication, disagreement, and laughter that followed capture a moment in London’s history and illustrate a microcosm of how London helped influence the world?

How did the city make the empire and how did roast beef and a few glasses of claret help make the city?

Nineteenth Century London: The Empire and Modern Urban Studies

The Immortal Dinner was held at a crucial moment in British and London history. In 1805, Britain had won the naval Battle of Trafalgar against a combined French and Spanish fleet. The smoking-sinking triumph secured British global naval (and hence trade) supremacy for the next century. Just two years before the beef was roasted and the claret poured, an English and Prussian alliance had defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, leading to his exile and the end of the decades long Napoleonic wars. Of Trafalgar, James Hamilton wrote,

This spontaneous mood of pride and resolution after a naval engagement far away marked the beginning of a tidal flow which carried London through a century of growth and change on a scale unprecedented in human history.

In response, the population of London increased from 1.1 million in 1801 to 6.6 million in 1901. Burgeoning nineteenth century London certainly offered its glories. The Royal Academy of Arts was opened in 1768 to promote British painting, sculpture, and architecture. On payment of a modest fee, everyone could attend and gawp at the feted annual exhibition. The National Gallery, built by William Wilkins, was established in 1824 with the mission of bringing people and paintings together. The British Museum, aspiring to cover all fields of human knowledge, was opened in 1759 and became free to the public in 1805, resulting in a surge in the number of visitors, from 68,000 in 1829 to 500,000 in 1842. A flurry of city-builders also set to work transforming the city. John Nash started building London for new money – the bankers, tradesmen, politicians, and lawyers – resulting in the wooded lawns and elegant parades of Regents Park, Regents Canal, and Regent Street. Sir John Soane built the Bank of England, the Law Courts, and Offices of the Board of Trade. Sir Robert Smirke oversaw construction of the British Museum, Kings College, the Carlton Club, the Royal College of Physicians and the Central Post Office. Charles Barry similarly headed the construction of the Reform and Travellers Clubs, Decimus Burton the Athenaeum and Regents Park Colosseum. On 16th October 1834, the House of Commons caught fire and after 1840, Barry also worked alongside Augustus Pugin to rebuild it as a vast Gothic Palace of politics.

Nonetheless, London still contained a darkness within: “London in 1805 was vast, filthy and growing like a cancer.” But there were energetic efforts throughout the nineteenth century to tackle these problems. The 1829 Police Reform Bill created a 3,000-strong uniformed Metropolitan Police force. The lack of piped water and reliance on the river Thames helped contribute to city-wide cholera outbreaks in 1831-2, 1832, 1833, 1848-9, and 1853-4. The construction of a new sewage system was begun in the 1860s. Some efforts were made to tackle the slums through Acts in 1885 and 1890, which opened the door for progressive local authorities to construct public housing.

The exploitative British colonial history constituted the darkness without, draining wealth and resources from around the globe to build the glories of London. From this perspective, London was the creation and reflection of empire and colonialism. London was growing amidst the great expansion of Britain’s global empire: New Zealand became a colony in 1840; Britain annexed Hong Kong during the Opium Wars against China between 1839 and 1849; after the Sikh Wars concluded in 1849 and Britain defeated a large-scale mutiny in 1857, India was formerly annexed to the Empire; Britain participated in and was the chief beneficiary of the Scramble for Africa after the 1880s, which included the annexation of Egypt to empire in 1882. The fictional, but sagacious companion of Sherlock Holmes, Dr John Watson, said of this process in A Study in Scarlett:

I had neither kith nor kin in England, and was therefore as free as air—or as free as an income of eleven shillings and sixpence a day will permit a man to be. Under such circumstances I naturally gravitated to London, that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained.

Writers such as Walter Rodney have discussed British and other European colonialism as a means of extracting wealth from colonies to fund consumption, investment, and glorious building in the colonial heartland. Utsa Patnaik estimated the current value of the colonial drain from India to Britain between 1765 and 1938 at $45 trillion. Much of London’s grandeur is evidently a product of empire. Trafalgar Square and Nelson’s column celebrated victory at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar. Lloyds Insurance started in a small London coffee shop then expanded to being one of the world’s largest banking and insurance houses after dipping into profits from the slave trade and slavery. The Elgin Marbles (from the Parthenon in Athens) became a glory of the British Museum, purchased under dubious circumstances from the Ottoman colonial rulers of Greece.

Modern urban studies offer us another view, which has yet to be fully integrated into the thinking of the global economic historians discussed above. This view sees cities not just as passive reflections of global and national economic forces, like colonialism, but as central forces of wider cultural and economic change.

Cities bring suppliers and customers closer together, which reduces transport costs. Workers migrate to big cities because interactions with experienced workers help them acquire skills, become more productive, and earn higher wages. Firms may collaborate, compete, share ideas and learn from each other, which encourages innovation and boosts productivity. Cities offer cultural amenities, restaurants, theaters, museums, art galleries, and many services more generally which are hard to transport and remain local goods. Public services such as schooling, health, and sanitation are subject to economies of scale and specialization, so are cheaper to provide for a dense rather than dispersed population. The larger the city as a market for output, the bigger a firm can grow and so enjoy economies of scale and lower per unit costs of production. In his aptly named book Triumph of the City, Ed Glaeser declares that cities do not make people poor, they attract poor people with the prospect of improving their situation in life. There is clear evidence to support these general contentions and Glaeser’s claim. For example, what Oxford University economics Professor Lant Pritchett called his ‘smell test’; there is a close association between the level of urbanization and GDP per capita in a global cross-country sample; over time income per capita and the urban population share increase together; countries that became more developed historically also became more urbanized; and countries that have experienced an acceleration of economic growth, such as China after 1980, also experienced an acceleration in the rate of urbanization.

In this view, the wealth, innovation, inquisitive drive, avaricious acquisitiveness, military capability, and good governance created by London generated the capability to conquer, trade, and invest in the rest of the world. What these urban scholars don’t do is show how these urban benefits occur in practice, beyond fairly dry statistical data. It is to the Immortal Dinner that we can turn to watch those urban benefits unfolding in real time.

The Immortal Dinner December 28th 1817

The immortal dinner was given by painter Benjamin Robert Haydon in his painting studio at 22 Lisson Grove, on 28th December 1817. The dinner was a microcosm of the intellectual life of the capital at a time of upheaval and change two years after Waterloo.

Haydon structured the dinner around a desire to introduce John Keats, then a young and rising poet, to the more established poet, William Wordsworth, and also to celebrate Haydon’s painting Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem. The painting was half-way completed: three years of effort and three years to completion. Haydon wrote about the Immortal Dinner on three distinct occasions: immediately after in a long diary entry, 24 years later as a long entry in his autobiography, and in 1842 in a letter to fellow diner William Wordsworth. Haydon described the dinner as “an evening worthy of the Elizabethan age”.

There is no contemporary or later description of the menu but we can reasonably assume that Benjamin Haydon – critically acclaimed for his art, but universally acknowledged for his pecuniary failures (he was repeatedly imprisoned for failure to pay debts) – would have served basic, but dinner-party appropriate staples, such as roast beef and bottles of claret.

The routes by which the three main guests walked to the dinner reveal different facets of London. John Keats walked slightly more than three miles from Wells Walk in Hampstead North London to Lisson Grove through countryside. Charles Lamb walked about two miles from Russel Street, through the vibrant fruit and vegetable markets of Covent Garden and the nearby Flower District. Wordsworth walked one mile through the fashionable, and newly constructed regency streets from Cavendish Square.

Following Keats 206 Years Later

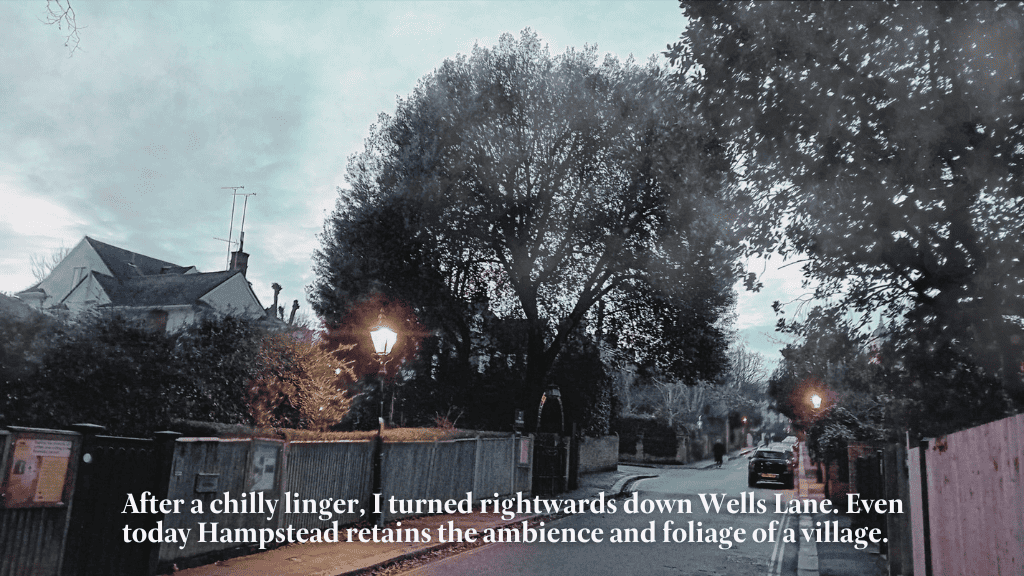

206 years later, on the 28th December 2023 the intrepid author of this blog re-traced the route of Keats from Wells Walk Hampstead to Lisson Grove. As was likely the case in 1817, it was a cold winter’s day, but the walk in 2023 was undertaken later in the afternoon, hence the grey gloom of the photographic journalism.

For an impoverished poet, Keats was residing in a rather delightful house, now converted into a museum to celebrate his memory. One would assume (I didn’t conduct the relevant research) he occupied an artist-appropriate garret room at the top of a narrow staircase, not the whole building? There is no record of the route Keats took to walk to Lisson Grove, but the most direct route would have taken him via the pastoral delights of Hampstead Heath and over Primrose Hill. Keats being noted for his Romantic poetry, I like to assume he walked this route. Quite possibly he walked a more urban route to pick up a bottle of wine for the dinner party?

There was a glorious gloom about my evening walk. For an economist (people once described as “knowing the price of everything but the value of nothing”), it inspired a degree of chilly-intrigue and poetic-romance.

The sequence above records my ascent of Primrose Hill. In the time of Keats, the hill was set amidst countryside, but today it is surrounded by fashionable boutique shopping, the homes of actors Jude Law and Daniel Craig, and is café filled London entrepot. In 2023, it was nonetheless still a peaceful, rustic, and lonely ascent, walking up towards the grey outlines of other late night hill lurkers. Once at the hilltop, the bright lights of London were suddenly revealed, sprawling out below. As in 1807, there was still a sense of leaving the rural and entering bright glittering modernity.

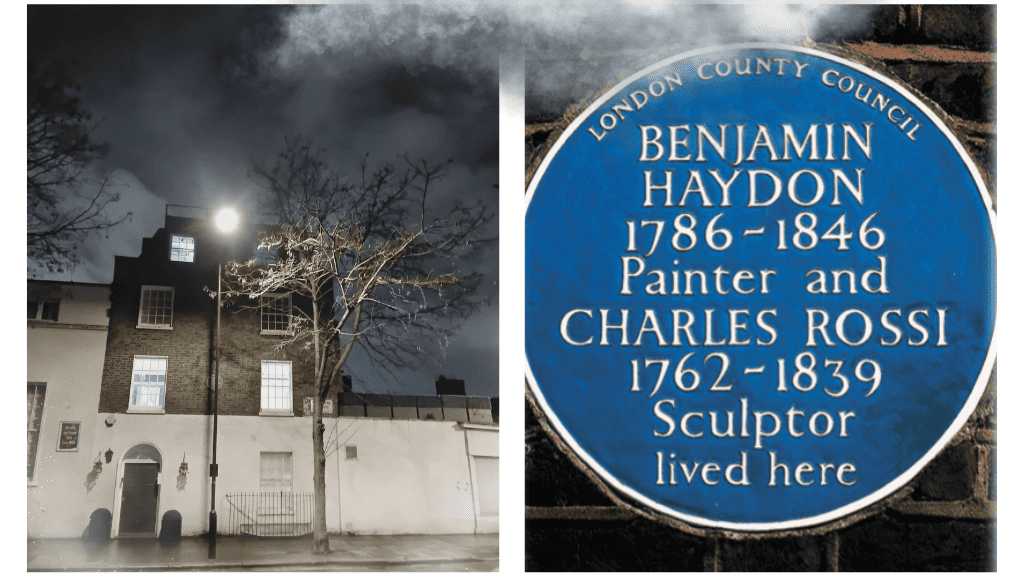

As per the writings of the urban scholars noted earlier, cities create opportunities for networking to mutual and productive benefit. Haydon certainly derived these economic benefits from London. He rented 22 Lisson Grove from landlord John Charles Rossi, also a painter and sculptor, and for sixty pounds a year, Haydon obtained a sizeable studio and ample living space. The immortal lunch and then dinner were held in the studio, beneath the 13 by 15-foot canvas of his half completed ‘Christ’s Entry’ The painting was centered on the image of Christ entering Jerusalem shortly before his crucifixion and contained a crowd adorned with faces, many of whom were known personally to Haydon (such as Keats and Wordsworth). The painting, though historical in theme, was very much a product of nineteenth century London.

The roster of guests that could have attended The Immortal Dinner, but ultimately did not, makes for a very distinguished list. Another great poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was not invited, perhaps for his known proclivity to engage in monologues rather than conversation, or perhaps that he had fallen out with Wordsworth? The essayist, critic, and journalist Leigh Hunt was a distinguished member of London literary society and as a friend of Haydon since 1813; his absence was a puzzle. In Haydon’s writing, there is a passing reference to a silver dinner service lent to him by Haydon that was not returned, perhaps that was the reason? William Hazlitt, a leading art and literary critic (whose face was also featured in Christ’s Entry) was not a Christian and less likely to appreciate the divine message of Haydon’s art. John Hamilton Reynolds (also said to be in the painting) was a poet, playwright, and satirist. As a friend of Haydon he did receive an invitation to the Immortal Dinner, but his failure to reply caused a rupture in their relationship. Urban scholars talk about the benefits of density, a mass of firms and workers able to connect. London in 1817 offered the benefits of cultural density. Those attending the Immortal Dinner only had a short distance to walk, as would many others who could easily have attended.

I reached 22 Lisson Grove at the hour the Immortal Dinner was transitioning from lunch to a louder and more raucous dinner, as Charles Lamb was slipping eloquently into intoxication, and as the later guests started arriving. I was in time to capture the evening gloom against which hot roast beef and rich claret would have offered such a welcome relief in 1817.

The Immortal Dinner was a Microcosm of 1817 London

Haydon was a voracious reader, able to converse freely in French and Italian and communicate well in Greek and Latin. Haydon was better at talking about art than painting; he gave lectures, published articles in art publications, and his journals were filled with art criticism. At the Immortal Dinner, Haydon had a “fine set to” (debate) with Wordsworth on Shakespeare, Homer, Milton, and Virgil. Lamb was described as “merry and witty” and there was a “powerful effect” on the guests when Wordsworth recited Milton. Haydon had included the faces of scientists, Voltaire, and Newton in Christ’s Entry and their artistic intrusion led to a discussion about the roles of science and religion. The artistically-inclined guests were agreed that the poetic imagination was under threat from increasing scientific knowledge. Lamb and Keats claimed that Newton’s work in optics had destroyed the poetry of the rainbow.

The Immortal Dinner was also attended by men of science. Evening guest Joseph Ritchie was a medical doctor-cum-diplomat, recently commissioned to lead an expedition to Africa, to travel south from Tripoli to Timbuktu in search of the source of the river Niger. Ritchie was to die en-route, inspiring not much more than a deflating Wikipedia epitaph. John Keats had also achieved medical qualifications but was being drawn away to the contemplation of beauty. John Kingston held the position of government Comptroller of Stamps and as a man of practical business, he inspired much drunken revelry from Charles Lamb for representing oppressive profit rather than artistic or even scientific creativity.

The conversation and debate about art and its relationship with science at the dinner reflected two powerful streams in 1817 London. This blog has already noted the ‘glories’ the art galleries, the museums, and the architecture of nineteenth century London. This was also an era of great London science. At The Royal Society (founded in 1662 but blossoming in 1817), mineralogists, physiologists, biologists, botanists, and chemists disseminated their discoveries to society fellows and their guests through weekly readings of papers. The Royal Institution of Great Britain (founded 1799) sought to introduce useful science and mechanical inventions into everyday usage. Humphry Davy, for example, lectured on the chemistry of tanning, dyeing and color printing, as well as the chemistry of agriculture to boost crop yield. Immortal Dinner absentee Samuel Taylor Coleridge also lectured at the Royal Institution on the principles of poetry.

Our host Haydon had arrived in London in 1804 to study at the Royal Academy. At the academy, through the introduction of fellow students John Jackson and David Wilkie, Haydon enjoyed the patronage of Lord Mulgrave and Sir George and Lady Beaumont, both of whom commissioned pictures from Haydon and kept him in busy employment between 1807 and 1814. More prosaically, Haydon drew on these networks to escape the consequence of his persistent debt for which he was imprisoned three times. Jeremiah Hunt, the governor of the Bank of England, once gave Haydon three hundred pounds.

Keats had known Haydon for a year and as a frequent dinner companion had even written a sonnet about his host. Keats was then enrolled as a medical student, but increasingly found a life in art more convivial. Earlier in 1817, Haydon had taken Keats to visit the Elgin Marbles at the British Museum. Inspired by the experience and making repeated visits to the marbles, ten months later, Keats completed the poem Endymion (‘a thing of beauty is a joy forever’) and in 1820 his masterpiece, Ode On a Grecian Urn. Wordsworth was not a fan of London, and preferred the picturesque Lake District in northern England, but valued London as a center of literary life. Lamb himself drew his inspiration from walking the streets of London and reveling in the opportunities of 24-hours of crowds, dirt, noise, and people, once exclaiming that “London itself is a pantomime and a masquerade”.

London offered that critical mass of a population necessary to support the efforts of painters such as Haydon. Christ’s Entry was completed in 1820, three years after the Immortal Dinner. The painting was exhibited in the Great Room at Bullock’s Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly for a whole year at a cost of 300 pounds. On opening night, the tragic actress Mrs. Sarah Siddons (a pioneer of the media celebrity) was heard to proclaim to her adoring entourage, “It is completely successful”. Once her pronouncement became widely known, the picture became fashionable. After London, Christ’s Entry went on a wider city tour and the Times and Observer newspapers gave it positive reviews. More than 30,000 people paid to view it and it generated 1,300 pounds profit – all of which Haydon had spent before the year was out.

Urban scholars offer us an alternative view of cities in general and of London in particular. While we may (or may not) accept the twin theses of London darkness, we should also engage with those ideas of cities as independent motors of cultural and economic change. Even if true, that colonial profits paid for London’s glorious architecture, it is also true that London trained and inspired Joseph Ritchie, who then sought to map the source of the African Niger river after the Immortal Dinner. But urban scholars, particularly the economists among them, are so dreary, their discipline rightly called the ‘dismal science’. We can learn about cities by staring in dull and glazed appreciation at a statistical presentation of the relationship between measures of urban density and their relation to measures of worker productivity, but it is far more convivial to join Haydon, pour a large glass of claret and participate in the urban benefits of learning, wit, and debate at The Immortal Dinner.

All dinners come to an end, even Immortal Dinners. Christ’s Entry came to a sad end. After being imprisoned again for debt in 1823, Haydon was forced to sell the picture, generously purchased by one of his ex-pupils for 220 pounds. The picture was first displayed in Philadelphia in the new American Gallery of Painting, then found a quiet retirement in a corner of Cincinnati Cathedral. Later large-scale religious pictures by Haydon, such as Lazarus, were exhibited to diminishing public interest and pecuniary profit. After repeated spells in prison for debt, failing to earn money from his art, being distracted from his art taking up commissions and portraiture to earn, and losing five of his ten children to various ailments, in June 1846 a broken Haydon committed suicide, by gun and razor blade in his studio. His grisly end did not tarnish fully the memory of The Immortal Dinner; Haydon had long been driven out of Lisson Grove by failure to pay the rent.