Connect with us

Connect with us

Discover how bad urban laws in Africa hinder city development and the daily lives of its residents.

Many of Africa’s urban laws are based on ones copied from those of colonizing countries, often with no regard for local concerns. These laws were developed to enforce the colonizing government’s control over the territory by restricting local access to cities and limiting people’s movement. Some postcolonial African governments tried to decolonize their legislation. However, most governments found the colonial legal systems useful in further tightening control over urban centers. Modern laws and policies were then developed to deal with the ongoing problems resulting from the colonial and postcolonial urban laws.

This research project examines the effect of these laws on the development of cities in Africa: How they shaped and are still shaping everyday life in urban Africa and how, in many cases, they are the source of many of the urban challenges the continent is facing. The research is organized into three main parts Spatial Planning Laws, Fiscal policies, and administrative policies. Looking at laws from colonial, post-colonial, and modern times to give an overview of how those laws shape current African realities. These documents can be found at the bottom of the page and are available for download.

Click on the map to learn about an Urban Law

Spatial Planning

Fiscal Policy

Administrative Policy

Egypt: Inadequate Building Laws

Tunisia: Labor Market Dynamics

Morocco: The “Museumification” of the Medina

Algeria: Strict Building Regulations

Kenya: Rapid Road Construction

Kenya: Confusing Building Regulations and Enforcement

Kenya: Spatial Planning Creates Racial Segregation

Kenya: Imported Building Code

Kenya: Outdated Property-Tax Rolls

Nigeria: The Land Use Act

Nigeria: The Joint Account System

Nigeria: Ban on Okada in Lagos

Sierra Leone: Land Ownership/Tenure

Sierra Leone: Local Councils versus Chiefdoms

Ghana: Strict Building Codes

Ghana: Customary Laws Generate Conflict

Malawi: Process of Tenure Formalization

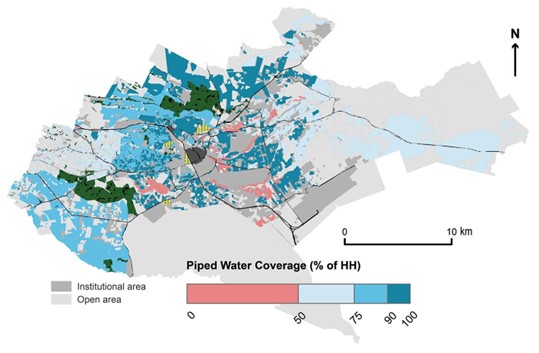

Zambia: Insufficient Land Tenure System

Zambia: Outdated Garden City Planning

South Africa: Failure of Social Housing

Tanzania: A Lopsided Mortgage Law

Uganda: Administrative Recentralization

Zimbabwe: Land Expropriation

Angola: Absence of a Mortgage Law

Angola: Customary Laws Dictate Urban Occupation

Guinea: Rural Land-Right Disputes

Somaliland: Nonexistent Land-Ownership and Property-Tax Register

Senegal: Dakar’s Municipal Bond

Lesotho: Patriarchal Forms of Landholding

Do you know of any laws in your town, city, or country that are having a negative impact on the lives of its residents or the development of the city? If yes, we would like to hear from you! We welcome you to submit your “bad urban law” using the form provided below. Our team will evaluate all submissions and add them to the map.

Below you can find our comprehensive collection of laws, categorized in downloadable PDFs. Whether you’re an urban planner, law student, or simply interested in understanding the laws that govern Africa’s society, you can find and access the relevant laws by using the interactive map above or by downloading our documents below.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive the latest updates and our published research papers delivered right to your inbox.

The Charter Cities Institute is a 501(c)3 nonprofit dedicated to empowering new cities with better governance to lift tens of millions of people out of poverty.

© 2024 Charter Cities Institute. All rights reserved.

In response to Egypt’s rapid population growth, which is projected to reach 160 million by 2050, the government embarked on a program of new city construction. Yet, these cities, positioned in remote, costly locations and lacking necessary amenities, have seen low occupancy rates. Additionally, Egypt’s building regulations, chiefly the Unified Building Law no. 119/2008, borrowed from European systems, created an urban fabric that neglects local customs and traditions. Designed to regulate informal construction, these laws cover various construction aspects, from building heights and street widths to architectural designs. Yet, implementation has been lax, resulting in numerous violations: an estimated 2.8 to 8.2 million from 2008 to 2018.

After a decade of the Unified Building Law, the government passed the Construction Violations Reconciliation Law no. 17/2019 (Amended by Law no. 1/2020) to regularize “illegal” buildings. Yet, by August 2020, only 688,000 out of an estimated 8.2 million violations had applied for regularization. The slow response is attributed to steep fines, bureaucracy, and a complex regularization process. The 2020 amendments escalated fines and introduced imprisonment for building on farmland. After a six-month grace period for regularization, the government started demolishing illegal structures, leading to the removal of thousands of buildings from urban and agricultural land. The government also halted issuing construction permits for private housing in Alexandria and Cairo due to persistent building-code violations. Despite the law’s harsh penalties and strict enforcement, its effectiveness in tackling informal construction and improving urban living standards remains uncertain.

Tunisia, despite seeing growth and development since its independence in 1956, has grappled with a weakened economy and ineffective governance, culminating in the 2011 Jasmine Revolution. Post-revolution, Tunisia’s economic recovery has been slow, with the country on the brink of collapse due to weak GDP growth and high unemployment rates. Key factors contributing to this poor labor market include labor supply pressures, skill mismatches, and ineffective regulations within its legal framework. Notably, Tunisia’s Labor Code, despite its 1966 revisions, contributes to these issues. Its strict regulations, which protect workers in formal employment, do not apply to the 50% of workers employed informally. The rigidity of these laws has also led to the proliferation of fixed-term and informal contracts, encouraging low-skilled jobs and hindering market expansion, formalization, and modernization.

This stringent labor code and inadequate job creation, especially in the context of an increasing supply of educated workers, have severely disrupted Tunisia’s urban environments. The high unemployment rates among educated youth lead to a ‘brain drain’ as they migrate out of the country, affecting cities like Tunis, which lose their skilled labor pool and potential for innovation. Simultaneously, Tunis, as a commercial hub, continues to attract low-skilled workers, leading to overcrowding and exacerbating social inequality. As these restrictive labor laws and job market dynamics persist, the city struggles with socio-economic imbalances, creating a challenging urban landscape and impacting its overall development trajectory.

During the early twentieth century, French colonial authorities in Morocco initiated the “museumification” of traditional medinas, asserting the superiority of French architecture and segregating Moroccan cities. French residents were concentrated in the modern “Ville Nouvelle,” while strict preservation efforts kept the historic districts stagnant and untouched, ostensibly to conserve cultural heritage. This process, controlled by the French protectorate, enforced their ideologies, governing urban development and city accessibility. Consequently, cities such as Rabat and Casablanca grew into French-style cities, while historic Moroccan capitals like Fez, Marrakesh, and Meknes were stifled by rigid codes and building regulations.

The enforced preservationist practices impeded economic opportunities and prohibited the medinas’ modernization, stunting their potential to attract new business and investments. This had far-reaching effects on both the social fabric and economic vitality of these areas. For example, the French transformed the Jamaa El Fna plaza in Marrakesh, a space historically used for temporary activities, by imposing geographical boundaries and emphasizing maintaining the physical structures of the building as is over the ways people interacted with the space. These conservation strategies not only alienated the social meaning of these places but also continued after Morocco’s independence through international entities like UNESCO, which promoted a European preservation approach. This restrictive outlook did not provide for the complete provision of public services in the medinas, continuing the stagnation of these historically significant areas.

In Algeria, a significant portion of building regulations date back to the French colonial era, governed by the code de l’urbanisme. Though Algeria gained independence in 1962, these codes, inharmonious with Algeria’s urban, political, and social fabric, continue to direct land development and construction. The urban inspector, following these codes, approves or denies building permits. Many provisions are excessively strict, expecting a replication of French suburban architecture, which proves challenging in Algeria. Certain regulations contradict cultural norms of this conservative Muslim country, such as the requirement for large, street-facing windows.

This disconnect between foreign building regulations and local building norms has led to a boom in informal settlements, especially after Algeria’s independence, when rapid urbanization amid an exodus of people from rural areas prompted a significant increase in informal construction. Many of those migrating to cities like Tlemcen could neither afford to comply with the stringent regulations nor participate in the formal housing market, resulting in extensive informal settlements on the urban periphery. These settlements typically lack fundamental amenities, such as running water, electricity, and sewer systems. Although attempts to reform and modernize the town planning codes are underway, the persistence of strict regulations continues to prevent residents from accessing the formal housing market.

Kenya’s rapid growth in sub-Saharan Africa has been driven by its focus on road construction, particularly in peri-urban areas around Nairobi and Kisumu. An acceleration in road construction was observed following the 2007 Kenya Roads Act, consolidating agencies responsible for road construction and streamlining approval processes. Consequently, Kenya’s road network has almost tripled in the last decade, with significant projects such as the Thika Superhighway and the Nairobi Expressway. Despite these ambitious initiatives, some Kenyan citizens have criticized the heavy construction, arguing that these projects will have a detrimental effect on urban growth.

The road construction boom, initially intended to modernize Kenya and alleviate urban congestion, has instead exacerbated various social and economic problems. These projects have intensified economic inequality, spatial segregation, environmental damage, and congestion. For instance, the Nairobi Expressway primarily benefits the economic elite who can afford to pay the tolls, leaving the majority of Kenyan vehicle drivers—operating matatus, minibuses, motorbikes, and taxis—in congested streets below. There are fears of increased urban sprawl resulting from these highways, and there have been environmental protests over the destruction of endangered trees and habitats.

Kenya’s rapid urbanization has led to a growing crisis of building collapses as a result of improper enforcement of building regulations. The complexities of these regulations, administered by both local governments and the National Construction Authority (NCA), complicate the situation further. A key law at the center of this issue is Kenya’s Physical Land Use Planning Act. This law confuses and complicates relations between local governments and the NCA, often leading to the approval of low-quality buildings.

The NCA (Defects Liability) Regulations are a response to this crisis, stipulating that commercial building owners have seven years from the passage of the act to recall contractors to fix defects at their own expense. Builders and contractors have contested this law, arguing it significantly raises development costs and constitutes an overreach by the NCA. This law’s potential to improve building standards in Kenyan cities remains unclear, but a solution is needed urgently. Poor Kenyan citizens, who mainly reside in informal settlements which comprise up to 70% of Kenyan cities, bear the brunt of these substandard building regulations as most of their houses are mixed use. Climate change has worsened the situation, with increased torrential downpours and flooding claiming many lives and affected many livelihoods. The lack of proper regulation enforcement continues to put Kenyan lives at risk.

Kenya’s urban segregation can be linked back to the British colonial period, when land in Nairobi was partitioned into exclusive residential areas based on race under the Nairobi Municipal Committee regulations and the Land Acquisition Act of 1894. These legislations enabled the colonial government to seize and segregate land for Europeans, Asians, and Africans. This racial segregation, which shaped the city’s development, persisted even after Kenya’s independence in 1963, evidenced by census data showing the majority of the population residing in formerly race-specific areas.

This spatial planning limited Africans’ access to land, pushing them into substandard housing and informal settlements, particularly in the city’s eastern parts. From 1952 to 1979, the number of these settlements ballooned from around 500 in 1952 to nearly 111,000 in 1979. The result is an extremely high population density, with about 70% of Nairobi’s residents living on just 5% of the residential land (or 1% of the city’s total land). These congested areas often lack essential public services, proper governance, and electricity access, and they grapple with high unemployment rates and crime.

Nairobi, like many sub-Saharan African cities, reflects British urban planning principles, mirroring the architecture and land uses of London. This is due to Kenya’s adoption of British building codes, brought over by a civil servant who copied the laws of his hometown, Blackburn, for Nairobi. These bylaws included British standards for a “proper” dwelling, leading to inapplicable requirements, such as roofs built to withstand six inches of snow, despite Nairobi’s warm, temperate climate. Although these regulations were first revised in the 1970s, with the latest update in 2009 and further changes proposed in 2020, they still embody foreign principles. For instance, the codes use imperial units, although Kenya switched to the metric system in the early 1970s.

The ramifications of these outdated and inappropriate regulations are significant. The codes mandate specifications, such as minimum distances from the street, minimum room sizes, and specific facilities, that are impractical for most of Kenya’s urban low- and middle-income population. As a result, many dwellings don’t conform to the code, leading to an unregulated building sector with safety issues, such as frequent structural collapses. This situation also indirectly encourages the proliferation of slums, as some citizens, unable to comply with these impractical codes, resort to building homes without basic sanitation or clean water access. Thus, the persistent enforcement of non-native building codes generates both safety risks and living conditions issues.

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution established a two-tier system of governance, including a national government and 47 county governments, thereby increasing the counties’ fiscal responsibilities. The county authorities, responsible for providing basic infrastructure and services, derive significant revenue from property taxes, as outlined in Article 209. The prevailing legal framework for determining property rates, the Valuation of Rating Act, prescribes valuations based on market values to be revised every decade. However, property values reflected in the tax rolls have not been updated since 1982, despite current property values being 20-30 times higher. Historically significant for local authorities, property taxes contributed to 45% of Nairobi’s revenue pre-independence, compared to 23% in 2014-15, and a mere 0.01% of GDP at the national level in 2012.

This outdated property tax system has impacted revenue collection for local governments, with Nairobi County Council falling short of its revenue targets by 55% in 2020. This shortfall restricts the county government’s ability to provide essential infrastructure and services, such as clean water supply to Nairobi’s slums. Therefore, the outdated land-value taxation model, with its largely unadjusted property values, undermines local governments’ ability to meet their constitutional responsibilities effectively.

In Nigeria, particularly in the rapidly growing megacity of Lagos, urban policies such as the Land Use Act of 1978 have resulted in uneven patterns or growth. The Land Use Act was originally intended to address poverty by formalizing the housing market but has, over time, fuelled land disputes, slum proliferation, and uncontrolled urban expansion. The Act’s aim was to manage land use effectively by granting the government the power to acquire, transfer, or allocate land. Its goals were to counter land speculation, provide citizens with secure living spaces, and simplify the acquisition of land for public use.

Despite its intended objectives, the Land Use Act has complicated land ownership, making it more difficult and susceptible to manipulation. With the government as the intermediary, approval processes became sluggish and regional governors could fast-track land approvals for wealthier groups or corporations. Furthermore, the Act prevents foreigners from owning land in Nigeria, thus hindering international growth and investment. These issues are most prevalent in southern Nigeria, where protracted land rights litigation has delayed industry development, infrastructure projects, and the construction of affordable housing. This situation, in turn, has affected the average Nigerian’s income, impacting the country’s overall GDP.

As Nigeria progresses towards decentralization, some problematic regulations persist, particularly within the municipal banking and finance systems. A primary issue is the joint account system stipulated by Section 162 of the 1999 Constitution. This provision demands National Assembly approval for revenues intended for the State Joint Local Government Account. This system restricts local governments’ financial autonomy, making them reliant on national approval for their funding. Originally intended to prevent manipulation and misappropriation, this system has been abused, leading to numerous scandals involving misuse of funds, illegal deductions, and diversion of resources, eroding trust in the national government.

The impacts of this flawed system have been severe, significantly limiting local governments’ ability to finance recurring expenses and development projects, ultimately impacting their ability to serve citizens effectively. Consequently, urban areas face significant challenges, including inadequate provision of public utilities such as water, electricity, and sanitation, as well as poor infrastructure with deteriorating roads, schools, and healthcare facilities. This lack of funding also obstructs efficient waste management, creating significant environmental and public health issues. The joint account system, hence, remains a significant hurdle in Nigeria’s path towards achieving functional federalism and improving local governance.

To address transportation challenges in the burgeoning city of Lagos, Nigeria, authorities introduced the Transport Sector Reform Law of 2018, aimed at revamping the city’s network. The law, which prohibits certain vehicles while promoting others, specifically targeted okada (motorcycle taxis), as these vehicles were believed to contribute to congestion. Despite the widespread use of okadas among the working-class due to their affordability and availability, they were banned from highways and business corridors. The Lagos state government cited okadas as responsible for numerous accidents and fatalities, leading to an expanded ban in 2021, despite opposition from the public.

The okada ban has had profound implications for Lagos residents. Approximately 800,000 okada taxi drivers lost their jobs, with no effort from the government to re-employ them. Ride-hailing and ride-sharing industries took a hit as companies, fearing profit losses, ceased operations in Lagos. As a result, minibuses or danfos increased their fares due to the passenger influx, causing a steep rise in transportation costs for commuters. With seat availability dwindling, Lagos citizens often endure an hour-long wait in sweltering heat for a bus ride. Protests against the ban have erupted, frequently escalating into violent clashes between the police and okada drivers. Many consider the ban a “rushed decision” and suggest alternative congestion solutions like proper registration and permitting for okadas. Despite this, the Lagos state government appears determined to uphold the ban.

Sierra Leone’s land-ownership system, influenced by both colonial legacies and customary laws, is one of Africa’s most restrictive. The 1927 Protectorate Land Ordinance, still operational today, vests all provincial land in tribal authorities, chiefly composed of familial chiefs and councilors. Investors looking to develop land must navigate a complex system, seeking approval from both tribal authorities and the national government. Unfortunately, the monopoly of the tribal chiefs often leads to underutilization, preserving land within family circles. This system, coupled with other customary laws, discourages broad-based land ownership and stifles investment.

These land-tenure laws contribute significantly to rural poverty, leading to the expansion of informal settlements and slums in semi-urban areas. It’s estimated that around 75% of Sierra Leone’s urban population resides in such areas, often under precarious conditions. The regulations disproportionately affect women and non-native residents, often depriving them of property ownership. Although women legally have the right to own property, the number who do is significantly low, limiting their income-generation opportunities and influence in decision-making. The ordinance also bars non-natives from occupying land in a particular province without tribal authority clearance and settler’s fee payment. The result is a lowering of living standards, monopolistic land ownership, and hindered economic production.

In the aftermath of Sierra Leone’s civil war, the nation has sought to decentralize governance to tackle corruption and inefficient resource distribution. The Local Government Act (LGA) of 2004 aimed to strengthen local councils, promising to streamline responsibilities and delegate authority over permits and approval processes. It established 19 local councils focusing on primary services like education, healthcare, and agriculture, garnering initial widespread approval. However, the LGA has since demonstrated considerable shortcomings, chiefly the persistent conflicts between local councils and the traditional chieftaincy system.

Although LGA empowered local governments, these authorities lack adequate funding for public projects, as much of the tax-levying powers remain with tribal chiefs. Consequently, local councils must seek grants and funding from the central government, inadvertently restoring the decision-making power back to the center. Furthermore, the chieftaincies retained control over land management and local courts, putting local councils in competition with them, thereby consuming resources and causing conflicts. Adding to the woes, the Ministry of Local Government and Community Development (MLGCD), responsible for overseeing Sierra Leone’s decentralization, has displayed favoritism toward chiefdoms, undermining planned reforms. As a result, the local councils, already facing funding, staffing, and education shortages, struggle to address local issues effectively. The LGA, originally envisioned to drive decentralization, is falling short of expectations, and many Sierra Leoneans believe it’s time to seek an alternative path.

In Ghana, conflicts exist between customary land-tenure systems and modern laws, leading to complications in building standards enforcement. To address this, the Ghanaian government has passed numerous laws over the years, such as the Town and Country Planning Ordinance of 1945 and the National Building Code of 1996, aimed at regulating land use. However, noncompliance with these building codes is rampant due to the lengthy and complex process of obtaining a building permit. According to the World Bank, it takes a minimum of 170 days to secure a building permit in Ghana, ranking the nation 162 out of 185 countries. The framework for these standards, considered cumbersome and outdated by many developers, is largely based on colonial British standards, leading to wide dissatisfaction.

The cumbersome process of obtaining a building permit has led to approximately 76 percent of Ghanaian developments bypassing the process, resulting in widespread use of substandard building materials. This has made many buildings susceptible to collapse, leading to numerous casualties and significant property damage. The most notorious incident was the 2012 collapse of the Melcom shopping complex in Accra, which resulted in 14 deaths and 82 injuries. In response, the government introduced the Ghana Building Code (GS1207) in 2018, aiming to regulate the construction industry and improve building standards. This 1700-page document covers essential areas of the built environment, but its effectiveness is yet to be determined.

Land acquisition in Ghana, regulated by both customary and statutory legal systems, is laden with challenges. With 80 percent of Ghanaian land classified as customary, many private individuals and corporations prefer this process due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. However, the sector is riddled with issues including multiple sales of individual properties, exorbitant unofficial fees, and fraudulent transactions. Further, the process is paper-based, hindering access to reliable and real-time data on land transactions and records, though blockchain technology has been suggested as a potential solution.

The ramifications of this flawed system are considerable. Notably, vast areas of land remain undeveloped due to ongoing court disputes over land titles. Astonishingly, 57 percent of all court cases in Ghana are linked to land disputes, which can take an average of 10-20 years to resolve. This prolonged litigation erodes public trust in the judicial system, driving individuals to resort to violence or political influence to settle land-related conflicts.

Malawi’s tenure formalization process showcases how an inefficient institutional structure and bureaucratic sluggishness can deter residents from registering land. High procedural costs, indefinite timelines, and language barriers – registration is conducted in English, a language only 40% of the population is proficient in – all contribute to this resistance. The Registered Land Act stipulates a convoluted seven to ten-step process for plot lease application, often requiring a general surveyor to verify dimensions for unplanned plots, and adds fees for drawing, stamping, and development.

This bureaucratic labyrinth results in two significant issues. Firstly, it discourages land registration, leading to a drop in revenue from land-registration taxes. Secondly, it hampers urban investment and projects dependent on formal land registration to commence business operations. However, since 2016, Malawi has been pursuing substantial land reforms, promising improvements in land acquisition, taxation, and transfer processes.

Zambia’s land tenure system, a blend of statutory and customary laws, has spurred considerable contention. By default, all land in Zambia falls under state administration, except for areas explicitly exempted. However, Zambian chiefs have the power to implement customary laws, provided they don’t contradict written legislation or the constitution. This system’s intricacy often muddles the process of land ownership and conversion. The 1995 Lands Act, which allows the conversion of customary land into statutory land, added another layer of complexity. The complicated legal processes associated with these conversions often lead chiefs to allocate land at their discretion, circumventing formal procedures and further complicating land ownership dynamics.

To alleviate the confusion, the government launched the National Land Titling Program in 2014. This initiative aimed to clarify land ownership but was stymied by legal challenges due to the absence of a comprehensive Land Policy addressing customary land rights. With the majority of land in Zambia classified as customary, the legal ambiguities have caused widespread uncertainty over land ownership. Many people have chosen to avoid the complex legal procedures altogether, further exacerbating the confusion. Thus, the unresolved land tenure system in Zambia, with its convoluted blend of statutory and customary laws, has perpetuated a sense of uncertainty and frustration concerning land ownership.

During British rule in Zambia, the 1929 Town Planning Ordinance was passed, mandating that Lusaka be developed following the garden city model, favoring self-contained towns with abundant green spaces. However, this plan mainly catered to European residents, overlooking the needs of the local population. The ordinance essentially barred natives from planned urban areas, tying their presence in the city to employment passports. Hence, native quarters sprung up organically, often lacking adequate planning or service provisions.

Regrettably, Zambian urban planning remains anchored in this 1947 act, leading to undesirable outcomes given the ongoing population growth and persistent housing demands. Post-independence saw a surge of people relocating to the city, hoping for improved opportunities. The stringent planning laws coupled with scarce affordable housing have fueled the proliferation of informal settlements. It’s estimated that in Lusaka, 70% of the populace resides in such areas. This scenario has escalated poverty and disease, as more people find themselves forced to inhabit these zones. The enduring impact of these outdated planning laws attests to the pressing need for their modernization to address contemporary challenges and realities.

Spatial segregation in South Africa has deep roots in legislation, such as the Black Communities Development Act of 1984 and the Groups Areas Act of 1950, which worked to separate non-White and indigenous communities. Although these segregationist laws were repealed in 1991, their impact remains entrenched in South Africa’s urban landscape, maintaining the country’s cities among the most segregated globally. From 1994 to 2006, the government responded to housing needs with social housing projects via the Reconstruction and Development Program and the Breaking New Ground program, providing over 3.5 million homes. However, the focus on free-standing, individually owned properties often relegated housing to less costly city peripheries, inadvertently intensifying spatial segregation.

The introduction of rental units into the social housing program in 2006 aimed to foster a more flexible market, promising central locations and better access to economic and social benefits. However, rising real estate values, stagnant government subsidies, and lack of available land saw a return to peripheral, suburban placements for projects after 2011. This, alongside the tendency of social housing residents to move to central locations for job proximity, exacerbated conditions in already crowded informal settlements. As vividly illustrated by the 2011 census data, spatial segregation continues to characterize South African cities. Upcoming data from the 2022 census may shed light on current progress and the enduring impact of colonial segregation and historical policies on urban housing accessibility.

In response to Tanzania’s ongoing struggle to provide affordable housing amidst rapid urbanization, the government introduced the Land Act in 1999 to stimulate homeownership. However, the sections regarding mortgages became a point of contention for banks, who believed that the law inhibited them from repossessing land from defaulting debtors. Under pressure from the World Bank, the Tanzanian government amended the law, leading to the Mortgage Finance (Special Provisions) Act of 2008, which strongly favored banks in the event of a default.

Despite some positive outcomes of the 2008 Act, including an increase in the mortgage portfolio and providers, this law has adversely affected borrowers. The law allows for high annual interest rates of 15-19%, creating an unaffordable housing market for many urban Tanzanians. In addition, the law’s lopsided favor towards banks has led to excessively high collateral requirements, dissuading potential borrowers from taking out a mortgage. These disadvantageous policies have contributed to the surge of squatter settlements in Dar es Salaam, where nearly 80% of the city’s population resides in informal housing. Despite the government’s ambitious plans and efforts to eradicate these settlements, the flawed mortgage law remains a significant barrier to affordable housing in Tanzania.

Once hailed as a beacon of decentralization in Africa, Uganda’s government devolved fiscal and administrative functions to the local government through the 1995 Constitution and the 1997 Local Government Act. However, this progressive shift was reversed with the 2009 Kampala City Act. The Act diminished the city council’s powers, transferring them to the newly formed Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA). This change turned the elected mayor’s role into a ceremonial one while vesting executive power in a presidential appointee, thereby undercutting the opposition-dominated local government.

The ramifications of the Kampala City Act have been far-reaching, causing jurisdictional overlaps between the KCCA and the City Council. The City Council, stripped of key service provision roles that could increase its popularity, has been left to manage unpopular tasks like enforcing building codes. The Central Government’s move to build a new wastewater treatment plant in a wetland area in Kampala, typically a local government domain, has not only infringed upon the City Council’s authority but has also incentivized illegal constructions in city’s wetlands. Consequently, a 2021 crackdown targeted 504 buildings for demolition. This example demonstrates how partisan politics can reshape local government structures and impair urban service delivery.

Upon achieving independence in 1980, Zimbabwe embarked on a land reform program to rectify the significant disparities between White landowners and Black subsistence farmers. The Zimbabwe Land Acquisition Act of 1992 gave the government authority to acquire land for redistribution after a small payout. White landowners had limited recourse to challenge the compensation amount and could not dispute the land acquisition. This was exacerbated by the Fast Track Land Reform Program in the 2000s, spearheaded by pro-Mugabe veterans, which violently displaced White commercial farm owners, without compensation, and nationalized about 42,000 square miles of farmland. Despite legal challenges, the government upheld legislation barring White farmers from challenging expropriations in court.

This land reform had severe repercussions. Notably, the process was plagued with corruption and irregularities, with land mostly distributed to political allies, many of whom lacked agricultural expertise. As a result, food production dramatically plummeted: Zimbabwe, once Africa’s breadbasket, was producing only 40% of its previous output by 2010. The economic impact was equally devastating, as Zimbabweans’ per capita income dipped from $1640 in 1998 to $661 in 2008. As food prices soared and formal employment opportunities dwindled, especially in cities like Harare, citizens became increasingly dependent on humanitarian aid.

Following the civil war 2002, the Angolan government launched a significant initiative in 2009 to build a million homes. Despite these efforts, a severe housing shortage persists, with an estimated one-third of the population living in substandard conditions. The government attempted to mitigate this problem by contracting with Chinese firms to construct apartment buildings, but these units are unaffordable for most Angolans. The lack of a mortgage law in Angola drives this mismatch. Without a legal framework, high interest rates are common, averaging 19.295 percent in 2019, rendering loans inaccessible to a population where two-thirds earn less than $2 daily. Thus, despite banks offering mortgage loans under strict conditions, the majority are left without this financing option.

The absence of a mortgage law’s impact is evident in Kilamba, a new residential project near the capital, Luanda. Despite being designed for half a million residents, these apartments, priced between $125,000 and $200,000, remained largely unoccupied due to their high prices. In 2013, the president ordered a price reduction, and a state-backed mortgage scheme was made available to all Angolans, leading to a significant increase in occupancy. However, by 2019, the larger units were still vacant, and around half of the apartment owners who used the state-backed mortgages had defaulted on their payments. This situation underscores the urgency for a comprehensive mortgage law to ensure affordable housing for Angolans.

In Angola, postcolonial land laws have failed to integrate customary rights and practices, leading to extensive urban displacement. After independence in 1975, the exodus of Portuguese settlers left nearly half of Angola’s arable land vacant. The government claimed lands left unattended for more than 45 days. However, the process lacked clear legal guidelines, leading to customary law often taking precedence. Despite the introduction of the Land Law of 1992 and subsequent amendments, the legal status of communal land remained ambiguous. The government did not establish a practical strategy for regularizing irregular settlements, and many residents, burdened by illiteracy and lacking identification documents, struggled with official land registration.

The impact of these poorly conceived laws was severe. Post-2004 Land Law enforcement saw the government initiate a massive crackdown on irregular settlements, particularly in and around Luanda, the capital. Thousands of families were forcefully evicted, often without alternate shelters or due process, and in blatant violation of both international and Angolan law. Between 2002 and 2006, 18 mass evictions took place, razing over 3,000 houses, impacting 20,000 people. The evictions targeted poor residents who lacked the resources to secure their tenure or find alternative accommodation. Despite human rights and civil society organizations’ protests, the government continued with aggressive forced evictions, leaving evictees scrambling for inadequate shelter solutions.

Despite Guinea’s economic growth from expanding bauxite mining operations, particularly in the northwestern Boke region, the industry’s surge has intensified issues regarding land rights and spatial planning practices. Most pressing is the country’s poor customary land-tenure laws, compounded by the 2013 Mining Code. This legislation expanded land coverage for mines and hastened land-purchase agreements, aiming to create job opportunities and bolster national revenue. However, these actions led to significant land loss for rural residents—constituting around 70% of Guineans—often without fair compensation, as mining companies argue that under colonial land-ownership definitions, the government essentially owns rural land and doesn’t require residents’ informed consent.

The fallout of this legislative framework is evident in rural communities such as Hamdallaye, which was eradicated for mining in 2020. Residents have either been forcefully displaced or compelled to leave due to the land’s unsustainability for non-mining activities. Further, the mining pollution and high-water consumption from mining operations have diminished access to clean water, while dust from mines has polluted homes and air quality. As Chinese and Guinean companies form more joint ventures, mining sites encroach upon rural settlements, leaving residents feeling marginalized despite experts’ assertion that mining is crucial to the economy. This tension has led spatial planners and experts to seek a delicate balance between safeguarding communities and appeasing mining companies since 2017.

Somaliland’s capital, Hargeisa, struggles with a flawed fiscal and administrative legal framework. The land registration system was left in ruin after the Somali Civil War, and Law No. 17/2001, which places the power to register land with local governments, complicates matters. The law mandates development or tax payment within a year of land registration and failing to comply within two years risks forfeiture of the land. This legal provision has dissuaded many from registering, leaving only 15,850 registered properties in Hargeisa by 2004. However, with the advent of satellite data, the number of registered properties increased to around 59,000 in 2005, resulting in a revenue boost of 248 percent.

Somaliland’s decentralized governance system, established since its independence in 1991, requires local authorities to generate their own funding for services. With the low registration of properties in Hargeisa, the capital has struggled to provide essential municipal services, reflected in the city’s poor infrastructure. Thus, the existing law inadvertently hampers revenue generation, undermining the city’s ability to effectively address the basic needs of its populace.

Senegal’s decentralization policies, like the 1996 Municipal Code, were intended to empower local governments. However, despite increasing their revenues by 40% between 2008 and 2012, local councils still control just 10% of their budgets due to funding withholdings from national authorities. Dakar’s mayor, Khalifa Sall, tried to circumvent this through the Dakar Municipal Finance Program (DMFP) in 2009, aiming to launch Africa’s first municipal-bond program to help local governments raise capital.

Unfortunately, despite achieving investment-grade credit ratings and rigorous budgetary review, the Ministry of Economy rescinded its approval two days before the program’s 2015 launch, fearing national liability for potential defaults. This abrupt termination forced Dakar to suspend its ambitious program and continue working within a limited fiscal capacity. Although Dakar’s municipal bond project didn’t materialize, it provided valuable lessons for other African cities, showcasing potential alternatives for raising funds, with Cameroon and South Africa successfully launching their municipal-bond programs. However, cities in nations with decentralized governance but centralized fiscal systems, like Senegal, continue to grapple with such challenges.

In Lesotho, customary laws govern local communities. Although these laws help preserve cultural heritage, they can also perpetuate inequalities. Land tenure, a critical issue, is controlled by traditional elites via these laws, often disadvantaging women. The Deed Registries Act of 1967 exemplifies this bias, allowing officials to refuse registering property in a married woman’s name, if contrary to local customs, and instead register it under her father, father-in-law, or husband’s name.

Access to land, especially in rural or developing economies, can significantly enhance the accumulation of human and physical capital. Yet, in Lesotho, women often relinquish property rights to maintain harmonious relationships with male relatives. Consequently, the customary law deprives women of a critical financial resource, land ownership. Social and legislative reforms could potentially rectify this issue, paving the way for broader land ownership among women.