In 2023, I visited Lusaka, Zambia for two purposes, one of which attracts nodded heads of supportive encouragement for virtuous deeds, and the, other attracts narrowed-eyed glances of suspicion. The first purpose was to teach the course Re-thinking African Cities at the University of Zambia (UNZA). The second was to conduct two weeks of fieldwork among the bars, the pubs, the bar-pubs, and the pub-bars of Lusaka. After all that lecturing and discussion, the throat of this poor researcher was dry, it was hot weather in Lusaka when I visited, and besides I was also interested in looking at drivers of long-run economic development.

I used to live in Lusaka, between 1998 and 2000; back then it was quieter and lacked much of the vibrant nightlife (and early afternoon life, and late afternoon life, and early evening life – Lusaka is a very social place) visible in Lusaka today. In the late 1990s, I watched with awe as the first modern shopping mall was being built – Manda Hill; now Lusaka is full of malls and their associated watering holes for thirsty academics. Among the many that induce nodded heads of agreement when discussing the merits of locations to imbibe are the Keg and Lion, Latitude 15, Chicago’s Re-loaded, and Cloud 9. Zambian bars are less inclined than their Toronto counterparts to have a smart accompanying website, so forgive the lack of hyperlinks here. The bars and the spending happening within were an evident and very visual manifestation of the rise of a Zambian professional middle class, conspicuous by their absence from Lusaka in 1998.

Elsewhere in my research on Zambia, I have been looking at special economic zones in Zambia, specifically the Lusaka South Multi-Facility Economic Zones (MFEZ). I was interested in which industries it was targeting among foreign and domestic investors. The Lusaka South MFEZ offers special incentives, “to commercial and smallholder farmers through the linkages created by the agriculture and agro-processing industry.” The specific agro-goods for which the government seeks investors are “wheat, soyabean, cotton, tobacco, spices, sugar, and vegetables”. Beer and brewing were conspicuous by their absence. Under manufacturing, electronics, and electrical goods were listed as targeted sectors, but there was no active encouragement of brewing.

This was a puzzle, brewing and beer are clearly associated with economic development in Lusaka, but brewing appears to be ignored as a key driver of development by policymakers. This blog makes a more rigorous investigation than the thirst-induced claims of this researcher, of brewing and economic development in Zambia.

Whether in fourteen-century Hamburg (Germany), eighteenth-century London (UK), or nineteenth-century Toronto (Canada), breweries are generally among the earliest and largest industrial establishments. This makes breweries easy to locate and subject to taxation. There is a widely accepted moral case for alcohol taxation and consequently more support for taxing alcohol than other basic consumption items, such as food or energy. Brewing creates a product (beer) for which there is a demand that doesn’t change much when taxes increase its price (in the language of economics, demand for beer is price-inelastic). In short, brewing and beer are excellent sources of tax revenue, particularly for poorer countries that don’t have the governmental capacity to tax incomes. Not surprisingly, alcohol is a crucial source of revenue for governments across the global south. On their website, Zambian Brewers proudly proclaim that they paid almost $50 million in excise revenue in 2020, up 15% compared with 2021. This doesn’t include the VAT and other taxes on alcohol consumption paid by consumers at all those bars and pubs, including the research costs incurred by this researcher. It is the prior, convivial sipping in Zambia that helps pay for much of the foundations of long-run economic development, the schools, hospitals, and infrastructure.

Economists, such as Cambridge University Professor Nicholas Kaldor, have long acknowledged the unique contribution that manufacturing can make to wider economic development, through its impacts on generating employment, exports, productivity growth, and linkages with other economic sectors. Brewing has for centuries been among the earliest and largest industrial enterprises in developing countries. This was true of Europe in the early ninth century when brewing was done by monasteries; in the eighteenth century British Industrial Revolution; and in the nineteenth century when new technologies in refrigeration, train travel, and automatic bottling machines improved the ability of ever larger breweries to store and preserve beer and transport it at longer distances. In the US the number of brewers declined from 1,816 in 1900 to 101 in 1980, and their average output increased even more dramatically, from 2.6 million liters in 1900 to 219.2 million in 1980. The years since 1980 have seen this growth and consolidation of brewing on an international level with the emergence of multinational brewers including Heineken (Holland), SABMiller (South Africa), and Interbew (Belgium).

In contemporary Zambia, these same historical patterns are unfolding in contemporary time.

Zambian Breweries is one of the largest industrial establishments in the country; its website claims 900 employees. In 2022 Zambian Breweries announced a $80 million capital investment project that would double the production capacity of their Lusaka plant. This project represented one of the largest industrial investment projects in the country. Brewing in Lusaka sits at the center of a network of linkages. Zambian brewers rely on input purchases from local farmers and their beers are sold to a booming local pub, café, and nightlife culture that reflects the growth of a Zambian middle class. In 2021 it was estimated brewing supported more than 80,000 jobs in Zambia.

The structural patterns of demand in developing countries mean that the consumption of alcohol (and so tax revenue and employment) is likely to increase rapidly during the early stages of development. Brewing is a good bet for economic development. When North and Western Europe were in the early stages of their own development, between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries the consumption of beer grew very rapidly, reaching an average of 250 liters per person per year. The reason for this is that alcohol is a ‘normal good’ meaning that as an economy grows (positive GDP growth) the demand for alcohol increases. One study, using US data from 1970 to 2007 confirms this. The study finds that alcohol has an income elasticity of demand equal to between 0.5 and 0.8. This means that for every one percent increase in income, demand increases by between 0.5% and 0.8%. If Zambia achieves its targeted income growth (GDP) of 7 or 8 percent per year, this would imply a very rapid increase in demand for alcohol. Zambia has faced difficult economic conditions in the last few years, including a growth slowdown and a national debt default in 2023. Despite this, Zambian Brewers could happily report total volume increasing by 7% in 2022, demonstrating the clear economic resilience of brewing and beer in Zambia.

Beer consumption tends to peak at very high-income levels, this is probably related to health concerns, shifts to higher-status drinks such as wine, and government efforts to limit alcohol consumption and sales (developed country governments tend to be less reliant on alcohol tax as they have developed the capacity to better tax incomes and corporate profits). Studies have found that the turning point in per capita beer consumption occurs at average incomes (GDP per capita) of $21,000 or $29,000. A first reason for Zambian optimism is that in 2021 Zambia had an average income of $3,200 (GDP per capita), implying that per capita beer consumption is likely to be rising for decades to come.

A second reason for Zambia to be optimistic is that the country has a young population. In the US, peak beer consumption occurs in the 35-40 age range. In 2023, Zambia had a population of 20.6 million, 42% of whom were aged 0-14 (only 11% in Japan by comparison). In Zambia there is a mass population who will be entering their beer-drinking years in the near future, and beer production is poised to benefit from this demographic sipping dividend.

A third reason for optimism is that Zambia has a religious structure that inclines the country towards beer consumption. One study found that globally, Catholics and Protestants tend to drink more, while Jews and Muslims tend to drink less beer. An estimate from 2010 (the most recent religious data) found that 95.5% of the Zambian population was either Protestant (75.3%) or Catholic (20.2%), while only 2.7% were other regions and 1.8% declared no religion.

There is a widespread fear across much of Africa that domestic manufacturing production is high-cost and that opening up to freer trade will lead to cheap imports from China, Vietnam, India, and elsewhere displacing local production. If true, this implies that Africa faces an enduring risk of import-led deindustrialization, long-term import dependence, and a future locked into agricultural production or catering to high-end tourism.

Whatever the truth of this debate, it is not applicable to brewing, where local production tends to cater to local consumption. Despite the massive increase in most measures of globalization in the US between 1980 and 2014, domestic production declined relatively marginally from 98% to 86% of the local market. Imported beers tended to cater to the exotic high-end of the US market. In Germany, despite the free and open trading market across the European Union (EU) domestic production still constituted 93% of local consumption in 2008. In China, despite a massive increase in consumption of beer, by 2007 domestic production was equivalent to 99.5% of domestic consumption, and the leading brand Tsingtao, exported only 0.15% of its Chinese domestic production overseas.

The typical business model has been for MNCs to buy local firms and then produce domestically, both their own global beers and also local brands. In China, there was a flood of brewery-oriented FDI associated with greater openness and domestic consumption growth in the 1980s and 1990s. The strength of Chinese manufacturing is evident in the fact that local firms then conducted buy-outs of foreign investors, which led to Fosters, Bass, Carlsberg, and Asahi all leaving China in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The likely reasons for this distinctive business model revolve around the costs of transport and culture. The preference for serving beer in bottles, and local rules about returning bottles for recycling in Germany means that beer is expensive to transport over international distances.

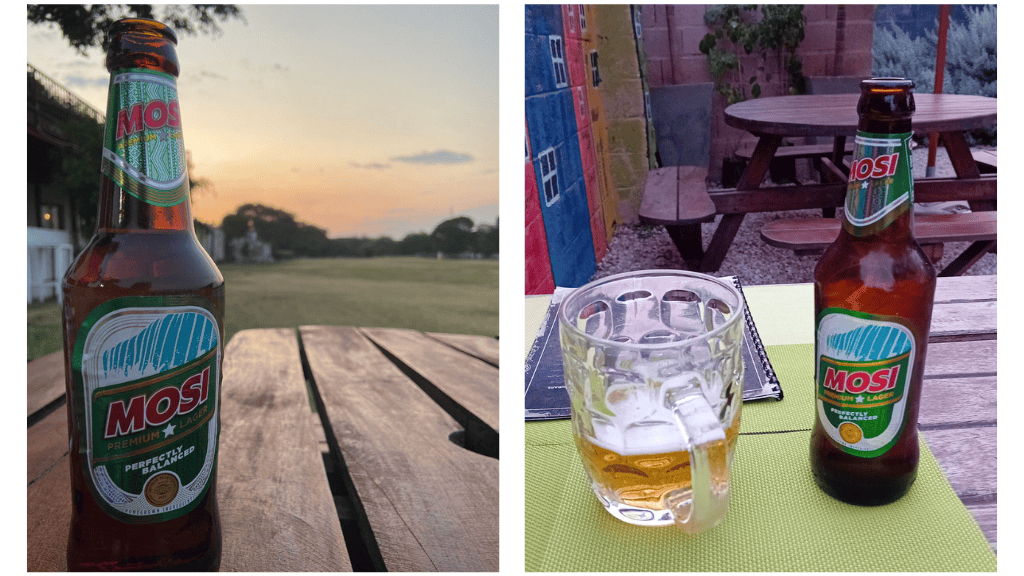

Contemporary Zambia fits with these patterns with aplomb. Zambian Brewers reported minimal exports, none in 2021, and only $750,000 of exports to Tanzania and Mozambique in 2022. Zambian Brewers was progressively bought out by foreign investors in the 2000s and 2010s, such that now more than 87% of the company shares are owned by the MNC ABInBev. This takeover was not used to facilitate imports; ABInBev started domestic production in Zambia of its iconic global brands (Carling, Budweiser, Stella Artois, and Corona) and also retained domestic production of the local brands that dominate the Zambian market (Mosi, Eagle, and Castle).

In Zambia, there is the added bonus that the country is still dominated by agriculture, so domestic consumption of beer is not just met by the domestic output of breweries, but production creates a wide network of local linkages. Zambian Breweries reported in 2022 that their supply chain is tightly integrated into local small-scale agriculture. In 2022 they partnered with “the Ministry of Agriculture, UN World Food Programme (WFP) and the Zambia Agricultural Research Institute (ZARI) to boost production of sorghum by small-scale farmers in Gwembe District of Southern Province.”. Zambian Brewers have a target, that by 2025, “100% of our direct farmers will be skilled, connected and financially empowered.”

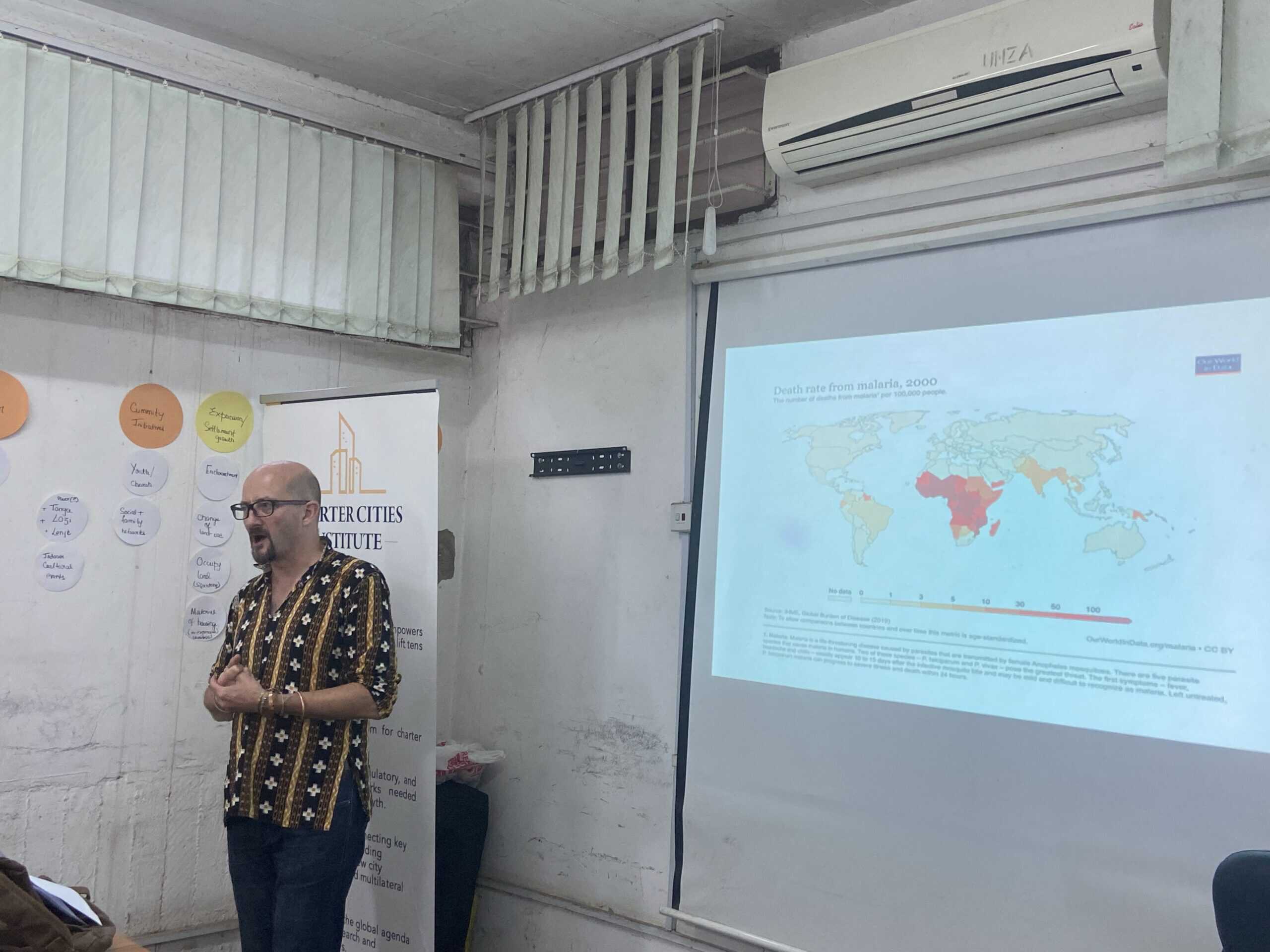

In late 2023 Zambia experienced its worst outbreak of cholera in recent memory. By early 2024, Water Aid was reporting that almost 8,000 people had been infected and more than 300 people had died. A sports stadium in the capital Lusaka was re-purposed as a treatment center and schools and colleges were instructed to remain closed until the end of the month. The outbreak was linked to the lack of clean water and proper sanitation. Historically the construction of good sewage and water treatment has had a massive impact on both morbidity and mortality, by reducing the incidence of diarrhea or illnesses such as cholera. One study uses data on mortality and access to water infrastructure for 80 neighborhoods in Paris between 1880 and 1914 when access to sewage increased from zero to 68% of all buildings. The study finds that connection to the sewage system had a “large and positive impact on life expectancy” and reasonably concludes, that “sewers saved lives”. Another study finds that the introduction of clean water technologies explained nearly half of the overall reduction in mortality between 1900 and 1936. Clean water was responsible for 75% of the decline in infant mortality, and around two-thirds of the decline in child mortality, and led to the near-eradication of typhoid; a waterborne disease prevalent until the early twentieth century.

The rate of return to clean water technologies has been estimated at 23 to 1, so why do people still die en-masse in countries like Zambia from poor access to clean water? The answer is that clean water technology, while simple and standardized, is often very expensive and inconvenient, as it involves digging up streets to lay pipes and intrusive access to private dwellings to connect them to the network. While the costs of clean water infrastructure are often borne by the government, the benefits are dispersed in the form of better health. It is difficult to charge for water connections to the poorest households. There is also a difficult politics of water supply. Much of the middle class in developing countries like Zambia have managed to insulate themselves from the costs of bad water by being able to purchase bottled water or home filtration systems, so they do not apply political pressure on the government to clean up water and are also not willing to pay the necessary taxation to make it affordable for the government to do so, as they will themselves receive no additional benefits.

Historically the brewing industry has provided an important source of economic incentive, political pressure, and personal influence to clean up water, including the city of Haarlam in the Netherlands in the sixteenth century or Toronto, Canada in the nineteenth century. These are not irrelevant historical examples; it is no surprise to see Zambian Breweries as equally engaged as their historical counterparts in efforts to clean up water in Zambia. Here a profit-driven incentive for Zambian Breweries is in alliance with the social benefits to a wider population of clean water. Zambian Breweries rightly make this link absolutely clear, in their 2022 annual report they present their corporate goal as

100% of our communities in high-stress areas will have measurably improved water availability and quality. Water is the largest input in the manufacturing of our products, and we believe that water is a shared resource and its access must be secured, particularly in high-stress areas. We continued to build new partnerships and strengthen existing ones to enhance the safe and clean water supply of the communities in areas where we operate. The conservation of both the Kafue and Zambezi River basins continues to be an area of focus in our partnership with WWF.

This aspiration was supported by practical endeavors.

This year we collaborated in a workshop with the objective of strengthening watershed protection initiatives and creating a working model to ensure the quality and measurable impact of our initiatives. We also remained engaged on the board of Lusaka Water Security Initiative and continued in joint action to celebrate World Water Day and World Environment Day, which called for transformative action on a global scale to protect the planet. Through this joint action we also supported various initiatives towards raising awareness and enhancing water access and security in communities around the City of Lusaka. At the Itawa Springs project site, we completed phase 2 of the project to enhance the sewer management system for the housing developed in the area. The project aims to ensure improved water quality in the watershed as well as adequate water and sanitation access for the surrounding community.

While loudly proclaiming their goal of attracting more foreign (and domestic) investment, especially in manufacturing, governments of the contemporary Global South can be disconcertingly reticent about investment in brewing. This blog gave one such example, the strange paradox of Lusaka in Zambia, brimming full of delightful liquid refreshment and a local MFEZ (special economic zone) that makes no mention of seeking to attract any sort of investment in brewing. This blog used the Zambian example to make a strong case for governments of the Global South to reconsider this lacuna and make strenuous efforts to attract investment in brewing. In 2024 brewing and beer consumption in Zambia, is good for mobilizing tax revenue, be a pioneer of industrialization, will experience decades of rapid demand growth (as incomes rise in a country with both favorable demographics and religious patterns), FDI will not lead to deindustrialization but instead stimulate local production to meet local demand and in the case of Zambia create new demands for the output of small-scale farmers, and also create a powerful corporate special interest in clean water that could have dramatic impacts on well-being across the entire country.

I ordered another bottle of Mosi-oa-Tunya – the favorite Zambian beer. The name when translated means the smoke that thunders and is the local name for the iconic Victoria Falls in the south of the country. I paid my VAT, and excise duty, and sometime later Zambia Breweries would pay more taxes on their profits. This wasn’t just research on a comfortable stool, this was liquid activism. In answer to the questions posed at the start of this blog. A liquid history of economic development in Lusaka, Zambia shows that given the choice of to beer or not to beer, we should definitely beer. I beer-ed and beer-ed again.

Unless this blog has entirely slated your thirst for the liquid history of development, you should consider reading, To Beer or Not to Beer Part I? A Liquid History of Economic Development in Toronto, Canada.