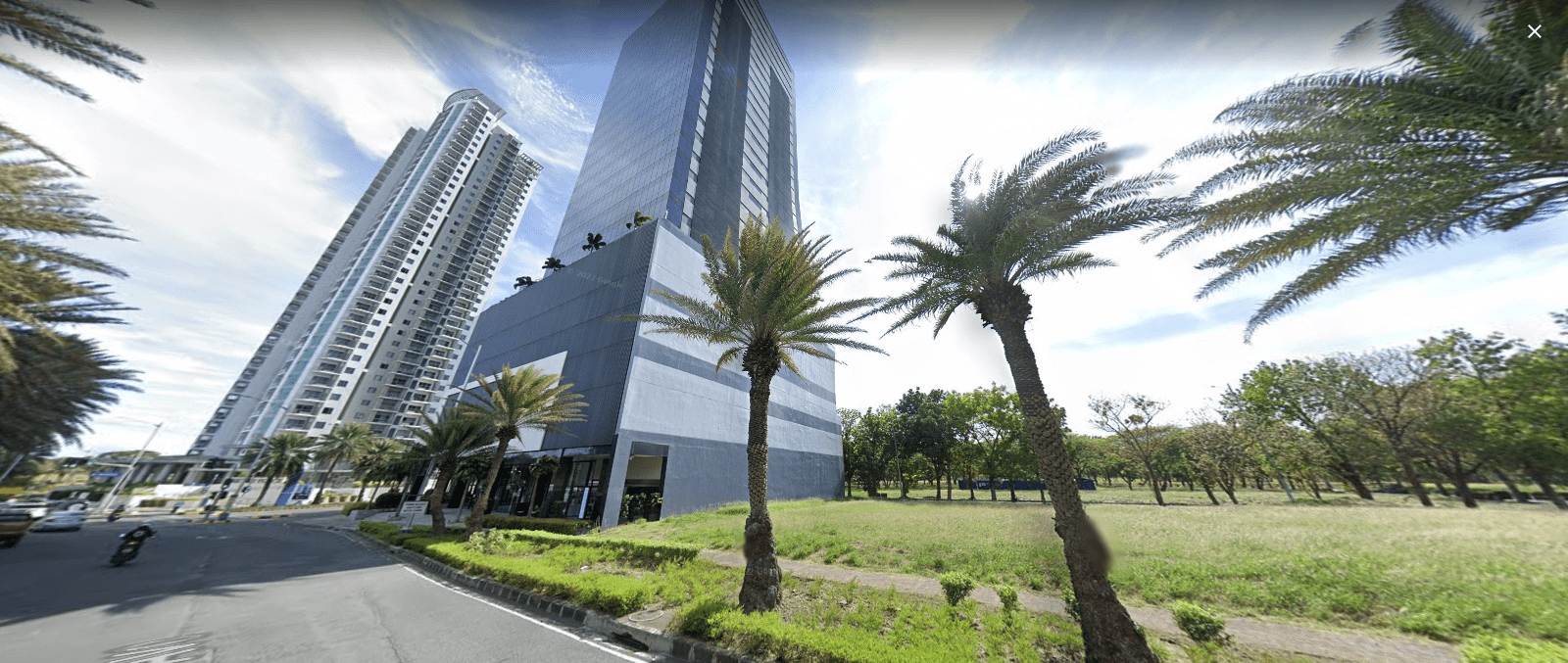

In December, I returned home to Manila for the first time in a decade. I grew up there, and my family lives there. I stayed in my family’s house in Muntinlupa, the southernmost region of Manila. Muntinlupa is typical for a modernizing Global South urban hinterland, in which it rapidly urbanized from rural farmlands and mango groves within a generation. During my childhood, the area had few amenities and unreliable public services. Today, Muntinlupa has skyscrapers, business parks, malls, fine dining, country clubs, and the first hospital in southern Manila. However, quick development comes with tradeoffs. Skyscrapers are placed next to single-family houses and informal slums, and expansive dirt plots interrupt the urban fabric. Rather than planning growth, developers engage in ad hoc projects that create an incohesive urban landscape.

Muntinlupa’s urban planning – or lack therefore – made it difficult for me to fulfill the rules for this series. My family lives in one of a cluster of gated communities. Stepping outside the house reveals streets eerily familiar to an American suburb. Every building is a single-family detached house and there are few sidewalks. If I walk 10 minutes in any direction, I’ll hit a wall, and it only takes 30 minutes to walk the subdivision’s perimeter. The closest thing to an amenity is a small clubhouse, which comprises of an event room and a community pool. Intent on writing something more interesting than a tour of Global South suburbia, I looked for the closest store in walking distance. It was a strip mall about 30 minutes away.

Source: https://www.lamudi.com.ph/lot-for-sale-in-ayala-alabang-village-1.html

To reach my destination, I had to access the main road, which required passing two guard checkpoints. The first was a checkpoint for my smaller residential subdivision, and the second was the checkpoint for the larger subdivision that contains my subdivision. The checkpoints felt excessively militarized, each with three guards armed with shotguns and assault weapons. Within 10 minutes, I stood by the four-lane main avenue, and to continue, I had to find a way to cross it without a crosswalk. I waited for the traffic light to turn red, then ran across dodging motorbikes.

The final stretch was a 20-minute walk on a thin sidewalk. On one side was a 10-foot wall with barbed wires, which protected Ayala Alabang Village, one of the largest and wealthiest gated communities in the country. On the other side was a busy road full of speeding cars. Although the road had a bike lane, it was more commonly used by small motorized vehicles trying to bypass traffic. The sidewalk itself presented its own obstacles, including an unmarked hole into the sewer and a herd of goats. Like many places in Manila, it sometimes felt safer walking on the edge of the road hoping passing cars would not hit you than to navigate a cluttered sidewalk in disrepair. During my walk, there were no other pedestrians.

Soon I reached a strip mall that brands itself as “Beverly Hills-themed.” The mall was an oasis. Its restaurants and open spaces offered a refuge from the chaotic streets I had just transited. I stayed for a coffee before heading back home.

This excursion illustrates key elements of Manila’s urban fabric. The first is exclusion. Gated communities like the one my family lives in are commonplace in Manila, even compared to other developing countries. These communities – colloquially known as “villages” – house both the wealthy and growing middle class. However, while most of the city does not live in gated communities, these communities still retain valuable public spaces and amenities. Unlike in the West, where gated communities are primarily residential developments, “villages” in Manila blur the line between public and private space. Many include commercial shops, schools, universities, hotels, parks, and medical centers. Some of these amenities are government-funded. In extreme cases, gated communities enclose entire towns and administrative neighborhoods (barangays), including their own public governments that work alongside private homeowners’ associations (e.g BF Homes).

While the consequences of villages are most harmful to the poor, I would argue that they are suboptimal urban environments for the wealthy and middle class as well. I stayed within a 20-minute walk to a couple friends’ houses, a café, and a basketball court. However, since those destinations are contained in the neighboring village, I could not access them without a village-registered car. Even returning to my own subdivision after my walk proved difficult, as I had to convince the checkpoint that my family lives there.

Villages in the core areas of Metro Manila – places like Makati, Taguig, and the City of Manila – are less common. However, these areas face their own exclusionary boundaries. The same real estate developers and landowners dominate urban construction, and there is an absence of public spaces. Except for a few parks, private shopping malls are the closest things residents have to a shared space. However, low-income Filipinos are kept out of these spaces by private security.

The second element is Manila’s car-centric design. Except for a few core areas, the city has no walking infrastructure or efficient public transportation. This comes as a stark contrast to other developing Southeast Asian countries, like Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam. In Manila, only those without a choice walk. I often likened the experience to island hopping. There were few opportunities to walk leisurely or “discover” activities. Before traveling, you had to choose a specific destination so that you could drive there. Even if something was a short 5-minute walk away, it was usually safer to drive.

These two elements – exclusion and car-dependency – have created a paradoxical geography. Manila is the most densely packed city in the world (Manila has 120,000 people per square mile compared to Manhattan’s 70,000 per square mile). Even Muntinlupa, which sits on the fringes of the capital, is incredibly dense at 35,000 per square mile. That’s denser than San Francisco and Washington, DC. However, the physical urban form contradicts density. Instead of crowded lively streets, people move around in cars or hide out in shopping malls. A lot of the crowdedness is concentrated in informal slums and high-poverty areas, where 30% of Manila’s population live. In contrast, many formal residential projects carve out expansive low-density “islands” for the wealthy.

Even Makati, Manila’s central business district, features relatively uninteresting street life amidst towering skyscrapers. If you Google “best streets to walk in Makati,” the top recommendations will be Greenbelt, Ayala, and Rockwell. All shopping malls.

Manila’s urban form may sound familiar to American readers. As a Singaporean once told me, “Manila is like mini-America.” This is not by coincidence. The Philippines underwent two prolonged periods of Western colonial rule that led to its modern urban struggles. From 1521 to 1898, the Philippines was a Spanish colony. As in other Spanish colonies, the mestizos developed into a landed gentry that persists today. In fact, many of the largest real estate developers in the country trace their origins to the Spanish colonial period. Consequently, land ownership is highly concentrated, which gives developers the power to force exclusionary developments.

Then, from 1898 to 1946, the Philippines was ruled by the United States. American urban planners sought to remake Manila using popular trends in the US (Lorenzo et al, 2019). In the core city, architects advocated for City Beautiful principles, such as wide avenues and monumental grandeur. In the later part of the 20th century, the Philippines relied on American urban planning consultants, who advocated for for car-centric design and suburban residential models. Aspects of Manila also resemble redlining in the US, in which urban planning is used to segregate society. Although Manila is slowly realizing that it needs to reduce car-dependency and develop inclusive spaces, the colonial legacy is hard to break.

Returning to the Philippines, I can’t help but compare it to my time in Vietnam. Both countries have about the same GDP per capita, yet Ho Chi Minh City offers a much better urban experience than Manila. While I only saw Vietnam through tourist lenses, the streets of HCMC appeared livelier and safer.

The lesson here is that hard infrastructure development is not enough. Oftentimes, overburdened cities in developing countries will try to “build out” of population stresses. Manila is a great example of this. While buildings are taller and malls are more luxurious, the core urban experience remains the same. It is congested, unsafe, polluted, and exclusionary. Manila is building new infrastructure, but not weaving it together effectively. This in turn generates as many urban problems as it solves, while channeling resources to a small group of elites. In contrast, countries at similar levels of wealth, like Vietnam, have more effective urban fabrics.

Policymakers should use good urban planning to do “more for less.” It doesn’t cost much money to plan urban development, but it is hard to rollback poorly placed infrastructure. Fortunately, the Philippines has a good opportunity to reorient its colonial urban past. Infrastructure spending in the country is growing, and many projects are on the district or city-scale. For instance, as part of an ongoing research project at the Charter Cities Institute (to be published later this year), we are catalogueing every new city project in the world. The Philippines includes New Clark City, a new administrative city that is planned to accommodate 1 million residents in 13 walkable neighborhoods.