There is a touch of Tooting Broadway, London about Kodigehalli, Bengaluru (in the south of India). Both originated as small towns on the outskirts of much larger urban entities and both have subsequently been swept up by urban spread. Bengaluru was once dubbed the most rapidly growing city in Asia and its crawling tentacles have long since absorbed Kodigehalli. Bengaluru is the center of India’s software industry, that paradox of an apparently high-tech sector in the midst of a poor developing country. These outposts of software production have contributed to what Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen once called ‘Islands of California in a sea of Sub-Saharan Africa’. India currently exports some $200 billion of software and ICT a year.

Kodigehalli has grown rapidly but boasts neither software nor any resemblance to California. In fact, Kodigehalli still retains some ambience of the small town, though the nice temple that was once the peaceful town center has now become a busy traffic island. Rather than ICT, it was instead old-fashioned transport infrastructure that spurred growth here. Kodigehalli has benefited from being close to the new airport road, which opened in 2008, connecting Bengaluru to Kempegowda International airport. The airport was named after a fifteenth-century warrior chieftain who promoted the growth of Bengaluru as an urban center of the Vijayanagara Empire. The naming of the airport follows recent Indian tradition. As India becomes more assertive in international relations – the country and its leadership dream of acquiring international Great Power status – the country is building statues of and renaming roads and infrastructure after historical martial figures.

If you were wondering…. Bengaluru was formerly known as Bangalore and retains this brand in the international software market. But officially, since 2006 it has been known as Bengaluru. The name better reflects the historical name of the city under the Vijayanagara Empire, rather than the anglicized colonial-British rendering.

Kodigehalli is built at a low level, sprawling outwards rather than upwards. This is strange. India has a population density of 1,202 people per square mile compared to 94 in the US. India is urbanizing rapidly. Land prices are high. Why did Chicago build skyscrapers more than a century ago while Kodigehalli (and India more generally) urbanizes via sprawl? I snapped a rooftop picture of the puzzle before setting out.

I walked down two flights of stairs and exited my building – Baldota Spring Woods – and, feeling bound by the habits of a two-blog tradition, I turned right. I railed about the absence of poets in my last blog (Phnom Penh). The poets of Kodigehalli are perhaps too poetic. There never have been any spring woods in the vicinity of the building.

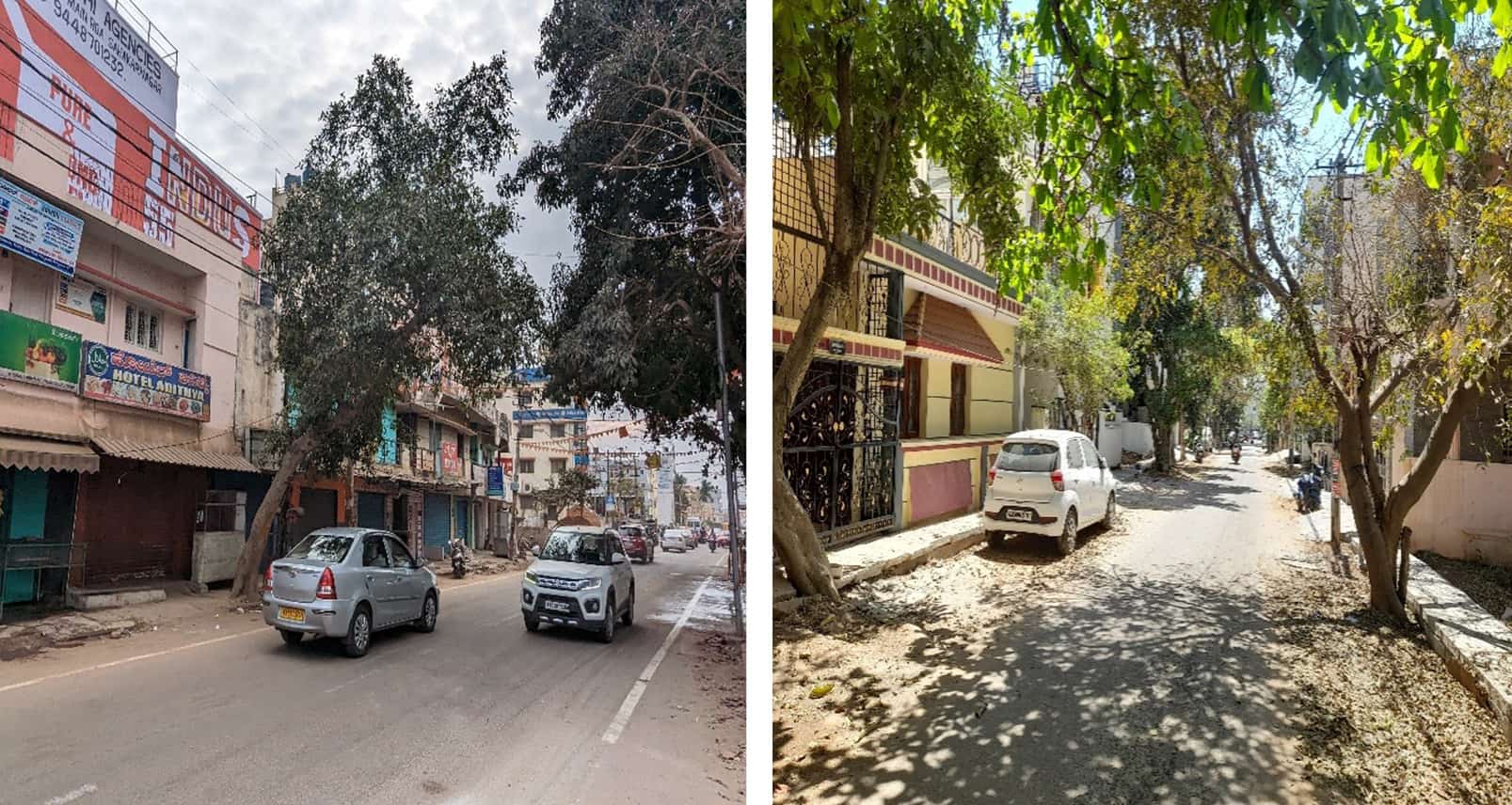

India’s very strict planning regulations are one reason for this low-level sprawl. Builders and architects face severe restrictions on vertical extravagance – a strict limit on the number of floors they can build. While the resulting unmet demand creates housing shortages and inflates property prices, this pattern of urbanization does create a nice ambience for the walker, where the trees are the dominant entity on the roads.

The Oxford University economist Lant Pritchett, argues that India has a Flailing State. At the center of Indian governance, the state has developed nuclear weapons, runs with fairness and efficiency the world’s largest democracy, and has a highly successful Mars Mission. However, as Pritchett argues, the head (the central government) is no longer connected to the ‘arms and legs of implementation’. Nurses and teachers don’t turn up to work, environmental and labor laws are openly flouted and the state struggles to collect taxes. Those strict planning regulations create an opportunity for nefarious entrepreneurship. Apartment blocks like to add an extra story from the number for which planning permission is given. The penthouse is available at a discount, in recognition of less secure property rights or the likely future demands for bribes from the building inspector.

Turning right, I ran into stark evidence of the flailing state. Government-provided public urban infrastructure is only ever partially completed. Numerous studies have found that contractors in cahoots with politicians compromise on infrastructure quality and use sub-standard inputs to skim illicit profits from construction.

Despite recent progress, only slightly more than half of rural Indian homes have access to piped water. The quality of water once it arrives is poor. Around 100,000 children in India per year die from diarrhea, 90% of those connected to water quality. One ‘solution’ to this failed public infrastructure is the physical delivery of water to houses, in bottles or via trucks. In the US, while tap water costs $2 per 1,000 liters, bottled water costs $1.20 per liter. The price difference is equally large in India. I see our local water truck daily.

The second photo is of an underpass at the extreme (15 minutes) end of the walk. It took eight years to build, an interlude during which the road crossed over the naked railway line. Sitting in a traffic jam, inside a car perched on a railway line always added a frisson of nerve to the already-enervating experience of reckless Indian traffic chaos.

India is an intensely politicized country. Second only to film posters (Bollywood and other domestic film industries) are political posters, either praising the developmental achievements of incumbents or the promises of aspirants. I passed several versions of this particular poster on my walk. It is a puzzle isn’t it! A very political country. A politician campaigning for office to build roads. And the evidently enduring poor quality of physical infrastructure.

Politicians generally use infrastructure to provide specific and targeted benefits: to give juicy construction contracts to supporters, to skim funds allocated for construction to themselves or supporters, or to provide benefits to specific vote banks (vote for me and your apartment block will get an electricity connection). Politicians like to provide infrastructure that they can clearly associate themselves with in the minds of voters. The more amorphous and less tangible aspects of infrastructure quality – such as clean water, reliable electricity, or good teaching in government schools – cannot be easily associated with the largesse of a single politician and doesn’t offer any opportunity to cut ribbons at an opening ceremony. Politicians like to build schools and employ more teachers, but worry less about the long-term quality of education.

While centrally mandated urban plans tend to separate residential, commercial and industrial activities, Kodigehalli is insistently mixed-use. I walked past numerous shops, several small metal working factories and a few nursery schools, all of which emerge from residential accommodation. The resulting emergence of Kodigehalli as a 15-minute city is an insidious grass-roots phenomenon. I like it. Yesterday my wall-clock stopped working; it took only a few minutes to return home with new batteries. When the clock was re-started, it was still telling a correct-enough time to cope happily with life in India.

Much of the commerce spills out into the niches of public space, as informal and small-scale trade. Around 95% of food purchases in India take place over these rickety tables. Supermarkets are only slowly making inroads into India. High levels of poverty combined with the (related) low level of refrigerator ownership means that households make daily and local small-scale purchases of basic necessities, such as milk (see later) and vegetables.

One interesting exception to the 15-minute-ness of the city is dining. Unlike in Phnom Penh, Cambodia and – as revealed by our other Asia blogs – Bangkok, Manila and Singapore, people in India snack on the streets but rarely sit there to eat full meals. In India, there is a tradition of eating at home en-masse with an extended family. The female labor force participation rate in India is only 25%, meaning that most women tend to be based in the household; in street-snacking Cambodia the figure was 74%. In India, women are more likely to be at home, buying locally and cooking under the gaze of their mother-in-law.

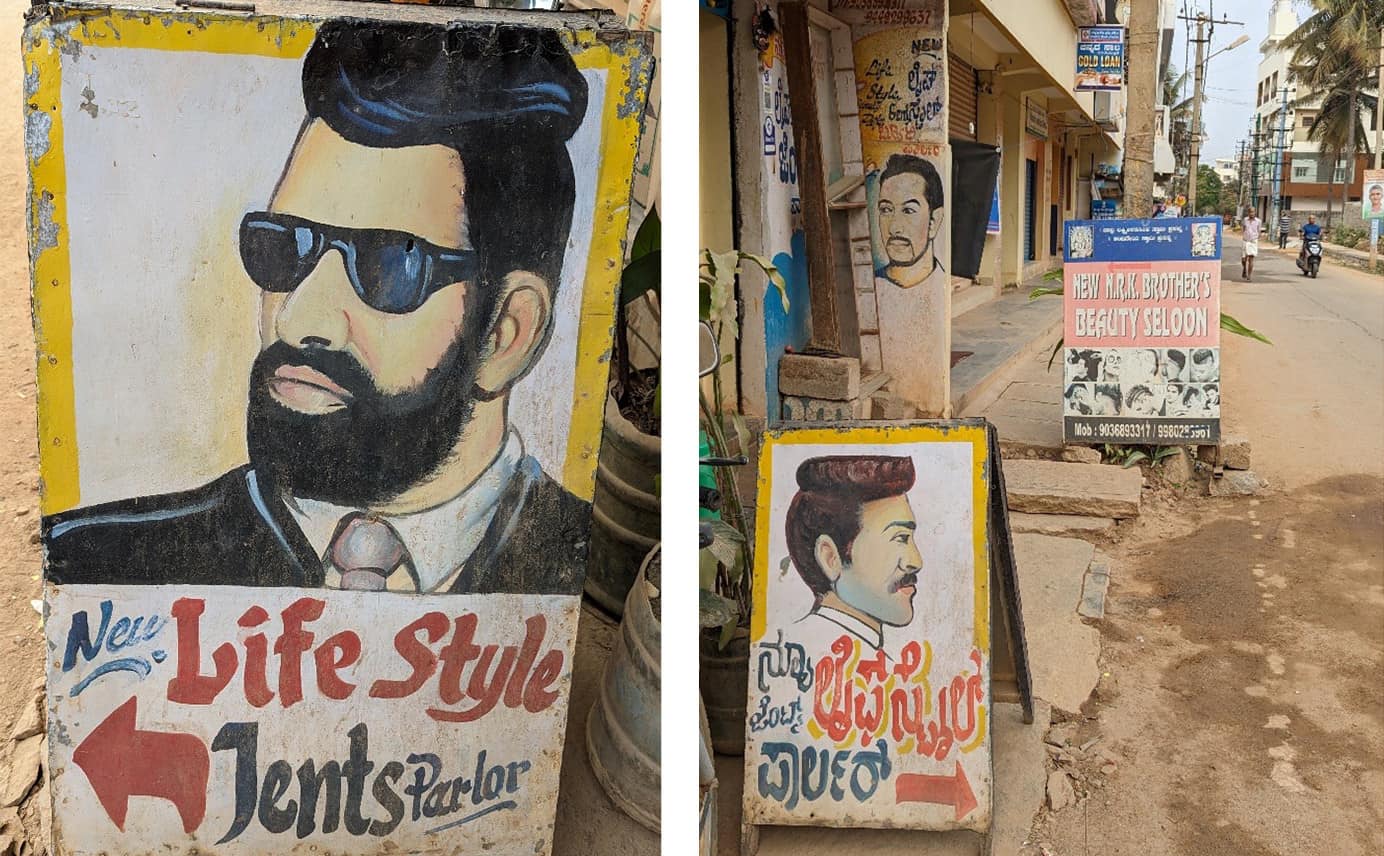

As I walked, I passed a barber’s salon whom I had recently patronized as a luxuriant customer. An old-fashioned interlude from a busy life – shave, cut-throat razor, haircut, hot towels, neck and head massage and eye-wateringly potent cologne – cost me $2. Unfortunately, I lacked the initial full-head-of-hair endowment necessary to give the barber chance to mold me into a full action-hero style.

Did you know that Indian policemen can receive a salary increment if they sport a moustache? Indian villains unanimously agree that the intimidating nearby presence of a moustache awes them into law-abiding conformity.

Any urban stroll in India will have to negotiate a very Indian tradition: cows strolling in-between the motorized traffic. The cows of Kodigehalli looked happy and plump when I overtook them. I am glad of this. Fresh milk is crucial for making Indian tea (chai), which is made from milk, tea leaves and spices boiled in a saucepan. Any literary vitality detected in this blog can be credited mainly to chai providing me with a vital morning pick-me-up.

City planning documents are often inspired by colonial-era planning laws, written by foreign consultants or imbued with a city’s desire to be ‘global’. As I turned from the main-road into a side street I could see the importance of local cultural norms and how they impacted urbanization. At a three-way crossing in India, the blocked fourth route is often considered unlucky (a site for voodoo said my local informer). Sometimes one will see the detritus (lemons) of curse-alleviating ceremonies. Often the unlucky plot is left vacant and used for car parking. Those houses that are built on a three-way crossing will often have a small religious shrine, with a protective deity staring resolutely at the three roads to ward off bad luck. Astrology, palm reading and other astrological conundrums are enduringly popular in India and people utilize local readers to identify an auspicious day or time for moving house or getting married.

My walk encompassed a pleasant thirty minutes. The pavements were as bad as those in Bangkok or Phnom Penh, but the newly built streets were relatively wide and spacious. There were fewer parked cars to slalom around as the housing and apartment blocks had internal parking space. Myself, my research assistant, the cows and the water trucks could amble through Bengaluru suburbia in relative peace. Even in the morning it was quite warm and all that attention to the economics, cultural norms, and politics of urbanization in Kodigehalli is thirst-inducing. Thankfully Bengaluru is a 15-minute city and it offered ample opportunities for informal, small-scale, thirst-quenching retail.

Over fresh coconut, we discussed what CCI can learn from Kodigehalli. What we noticed most was the informality that bubbled up from the grass-roots; how despite the dictates of planning documents Kodigehalli both evolved into a mixed-use neighborhood and acquired greater density through the construction of illegal extra apartment-floors that people were still prepared to buy. We also noticed the importance of culture and hence the advisability of urban planning being rooted in a deep understanding of the likely inhabitants. In Kodigehalli three-way junctions were not a good idea, local informal retail was crucial to everyday life and public spaces needed to accommodate wandering conventions of cows. The imperious political posters that gazed down on crumbling infrastructure told us that local politicians and democracy alone are not enough to deliver good infrastructure and public services.

The emphasis of CCI on public-private partnerships seems sensible as does their strong emphasis on ‘local’ in both the public and the private. The developer-manager model offered by CCI; whereby the developer has an incentive to provide public services to attract more residents and boost the value of land, and so land rents seemed like a good idea as we looked over the top of our coconuts at Kodigehalli.