For the past two weeks, I lived in Bangkok. This is my second stop on a two-month trip home to Southeast Asia (my previous stop was Manila). This is also my first time in Thailand. I stayed in the Thong Lo neighborhood, a trendy area with high-end restaurants, shopping, and nightlife. Thong Lo also houses Bangkok’s Little Japan and is a popular choice for expats moving to the city. I spent most of my time in the area between Thong Lo and Rattanakosin, a stretch of the city with the most developed tourist infrastructure.

Bangkok is a surprisingly organized city. Beneath crowded streets and chaotic traffic is a well-defined urban logic that, after just two weeks, made the city feel accessible and familiar. Part of this comes from the city’s strict adherence to road hierarchy. Narrow residential alleys connect to larger commercial collector streets before linking to the main (arterial) road. The alleys and commercial streets feel local and neighborly, and their dense assortment of amenities creates an effective 15-minute city. The main roads have broad sidewalks, skyscrapers, malls, and lively commercial activities. They cut through the city, connecting districts and neighborhoods. Bangkok’s two mass rapid transit systems – the MRT and Skytrain – run along these arterials. The pattern is prevalent enough to have its own nomenclature: narrow trok connect to larger soi before leading to a main thanon.

Almost every trip had the same routine. I’d leave my hotel, make my way to Sukhumvit Road (a major arterial highway that connects Bangkok to the Cambodian border), then walk or take public transit to my destination neighborhood. If I’m lucky, the restaurant or store I was patronizing would also be on Sukhumvit. Otherwise, I’d walk deep into the neighborhood, along hectic soi and winding trok, to reach my goal. Reading addresses was easy since streets were named in reference to their larger counterpart. Napha Sap Trok connects to Napha Sap Soi. Napha Sap Soi is also known as Soi Sukhumvit 36, which of course means it branches off Thanon Sukhumvit.

Bangkok’s road network felt like a river delta and its distributaries. This is not by coincidence. Bangkok, once called the “Venice of the East,” was defined by a dense network of canals (khlong). These canals were used to travel around the city. However, most of the city’s khlong have since been filled in and repurposed into roads. The consequence is not only a natural-feeling road network but a surprisingly small road footprint. Roads make up only 8% of Bangkok’s area, compared to 32% of NYC and 23% of Tokyo.

For this blog, I took a leisurely 30-minute walk around the neighborhood. I started in my apartment-style hotel 15 minutes away from the Thong Lo Skytrain station. The building was tucked into a small walled enclave that includes two mid-rise towers and a private parking lot. The parking lot felt like an internal courtyard, which brought serenity to an otherwise bustling city. Stepping off the property brings you to a narrow trok without sidewalks. Many of the buildings on the street looked like apartments, but there was also an Italian restaurant and a bakery. Most had the same “internal courtyard” architecture as my hotel.

The alley opens to a larger, more heavily trafficked soi. This road has some sidewalks, but they were uncomfortably thin, cluttered, and crumbling. In Southeast Asia, sidewalks often double as motorbike parking. Many pedestrians chose to walk on the side of the road instead. Cars and motorbikes loudly roared by, and it felt like it was the pedestrian’s responsibility to dodge them.

First, I turned right towards one of my favorite places in the neighborhood: the 7-Eleven convenience store. For those unfamiliar, 7-Elevens in Asia are a culinary destination stocked with interesting snacks and delicious prepared foods. Although this location had a large parking lot, the area was shared with various food stalls. This made a traditionally car-exclusive space feel lively and public.

Next, I backtracked towards Sukhumvit Road. In contrast to the previous trok and soi, Sukhumvi is heavily developed with well-maintained infrastructure. The sidewalks are wide and lined with tenji blocks for the visually impaired. The Skytrain tracks hover above, with a station almost every mile. Crossing Sukhumvit isn’t easy – cars are fast and crosswalks lack traffic lights. However, the Skytrain stations are handy overhead passes, and the sidewalks themselves are comfortable to walk on.

There are many things to love about Bangkok. The 7-Eleven parking lot shows how we can repurpose car-centric spaces for public enjoyment through mixed-use zoning (or in this case, a lack of zoning). Bangkok’s street stalls frequently turn unlikely places into commercial hubs. Likewise, the trok and soi embody walkable design best practices. They are narrow and residential, and they have just the right number of commercial amenities to feel neighborly but not crowded. The small setback of the building, in which the walls meet the side of the road, preserves the “sense of enclosure.” Urban planners might call them “human-scale.” The narrow streets are supposed to disincentivize cars from driving fast, and the lack of sidewalks reinforce pedestrian right-of-way. This road design is common in the alleys of Tokyo and Seoul, and Western urban planning advocates often point to them as models to emulate.

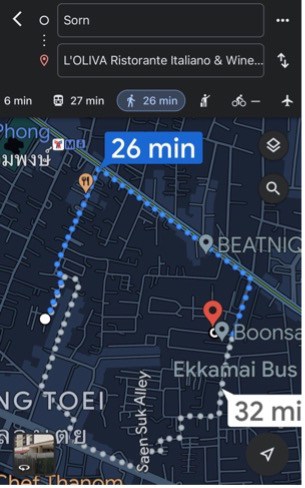

However, I couldn’t help but feel exhausted after my walk. It felt more like a hike than a leisure stroll. Despite one-way streets and a lack of formal street parking, vehicles were fast and hoarded sidewalks. I often felt like I was one misstep away from being hit. While navigating the city was comprehensible, it wasn’t efficient. Local roads usually ended in cul-de-sacs, which forced you to use the main thanon for inter-neighborhood travel. This turns what could be a 10-minute walk into half an hour.

There is a popular sentiment among Western urban planners that “human-centered urban design” is better than excessive regulations. This means we should build our environments in ways that nudge people towards good behaviors, rather than wield punishment to force good behaviors. For instance, instead of raising speed limit fines, we should build cities so that drivers are behaviorally disincentivized from speeding (e.g. narrowing streets). To incentivize people to ditch their cars, we should remove street parking and increase public transit networks. These prescriptions don’t always work in Bangkok. Whether you want to call it culture or unexamined conflicting incentives, the application of Western urban planning best practices isn’t straightforward in this city. In fact, some local experts have gone as far as to propose a Western anathema to address Bangkok’s problems: more roads.

The lesson from Manila is that you cannot “out build” urban dysfunction. If you do not plan development, then you may exacerbate preexisting problems. Bangkok, the capital of the fourth richest country in Southeast Asia, builds fast and plans well (at least by Global South standards). However, it appears that we cannot “out plan” urban dysfunction either. Even though Bangkok practices many desirable design principles, the outcome is still a hectic, uncomfortable, and unsafe pedestrian experience.