In January of 2020—before the COVID pandemic, before the Jan. 6th insurrection at the US Capitol, before the Russian invasion of Ukraine—CCI’s Founder, Mark Lutter, typed up what is now in retrospect a pretty prophetic tweet:

I think this tweet, given its prescience, deserves some unpacking.

I. Convergence, Big Time

I see Mark’s prediction as stemming from some variation of the Lucas critique. The Lucas critique basically says that when policies or institutions change, individuals will then incorporate the new reality these policy changes bring about and adjust their decisions, behaviors, and actions accordingly (in essence, agents will re-optimize to the new reality, and this re-optimization may spur yet other realities).

New research suggests that since the Third Wave of democratization in the late 1980s/early 1990s, combined with the IMF and World Bank’s simultaneous push for low-income countries to adopt a similar set of ‘Washington Consensus’ policies (roughly speaking, market-oriented reforms), the world has witnessed convergence, with low-income countries beginning to ‘catch up’ to high-income countries. The research suggests this convergence has happened not just across incomes, but also across institutional arrangements, education policy, health policy, and even culture (see this paper by Michael Kremer and co-authors; William Easterly comes to similar conclusions here; Lant Pritchett has some useful caveats on convergence here).

In light of the Lucas critique, it’s useful to then ask ourselves, “Okay, given policies, institutions, incomes, and other important things have converged over the last 30 years or so since the fall of the Berlin Wall, how will individuals across the globe re-optimize to this new reality?”

The short answer is—a la Mark’s tweet—first, a burning of the old, and then a weird emergence of the new.

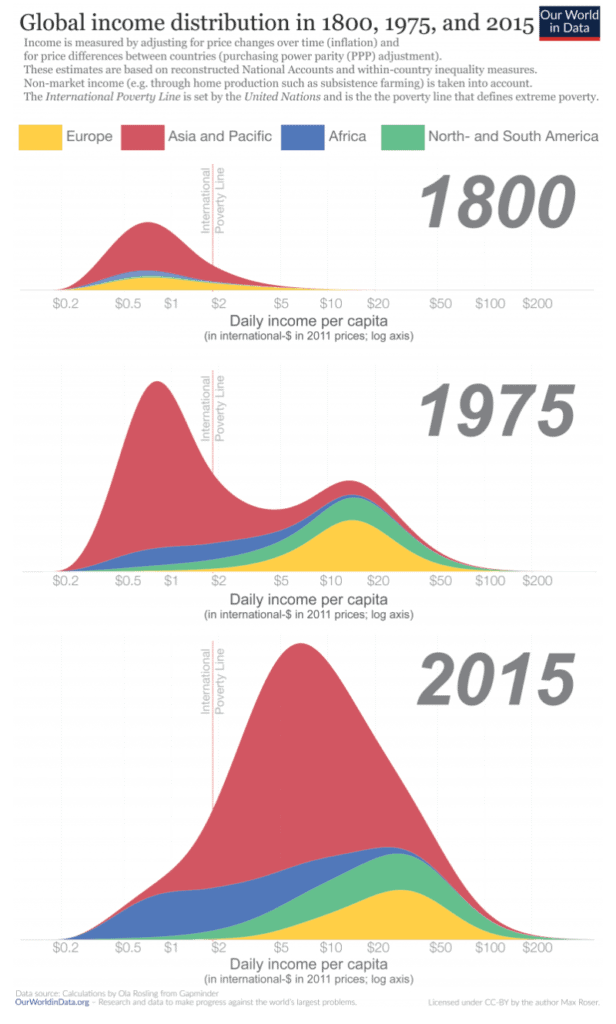

Throughout history, whenever incomes in formerly-laggard places or among formerly-laggard groups have quickly begun to catch up to the frontier (see, below, from OWID, which shows that pretty divergent incomes in 1975 saw significant convergence by 2015)…

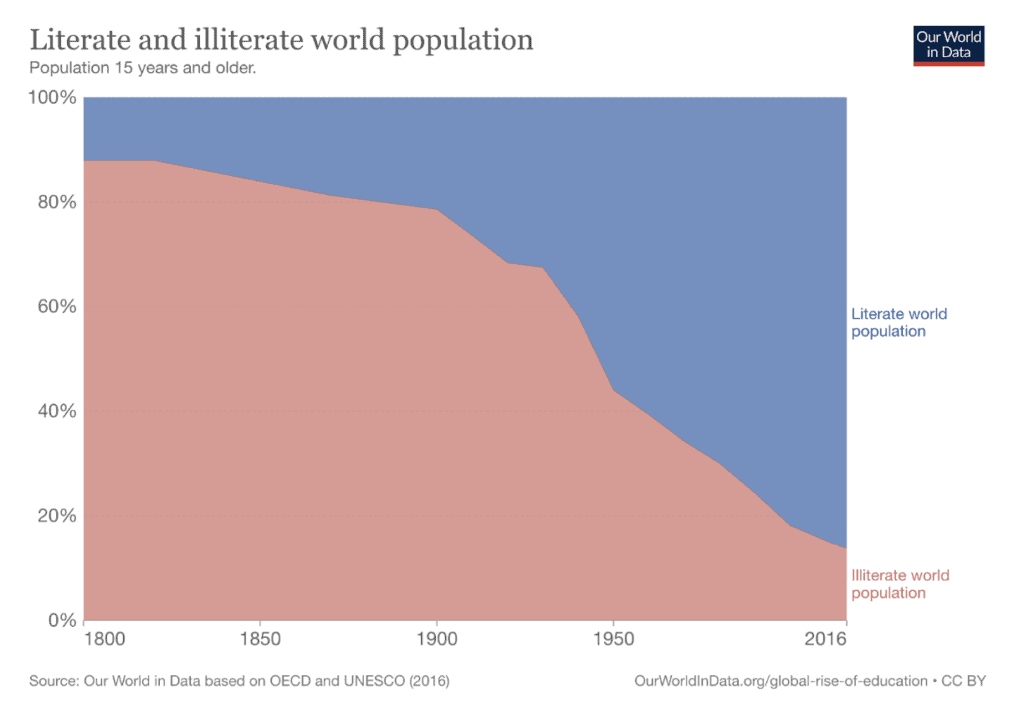

…and whenever these same places have, simultaneously, gotten a lot more educated (again, from OWID)…

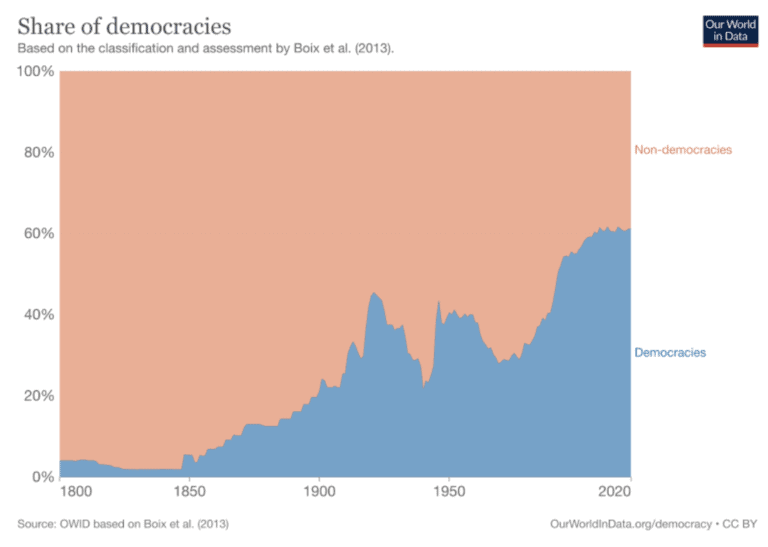

…and have also begun to live under more open political regimes, however nascent (again, from OWID)…

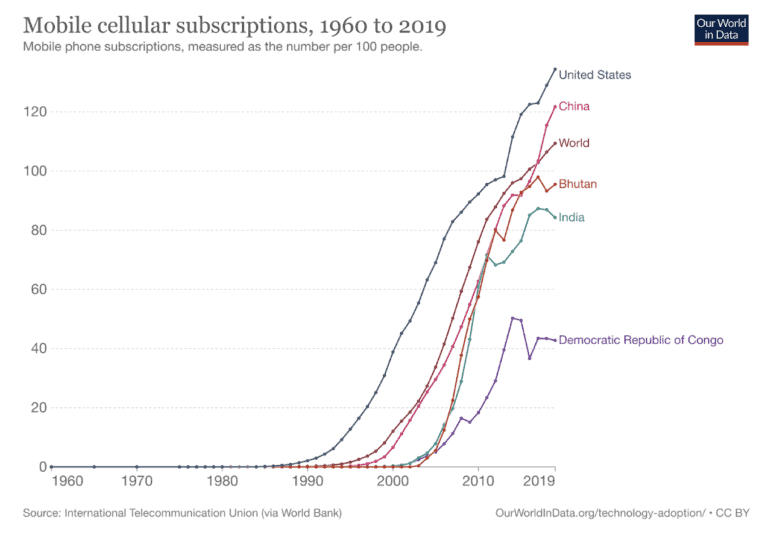

…and have increased access to new technologies that significantly decrease communication costs and improve the ability of individuals to connect with one another (again, from OWID)…

…history shows that when all of these mega-trends combine—quickly and at the same time—these newly empowered groups and places will be fundamentally altered. And, as per Lucas, a re-optimization will occur. The question then becomes how will institutions adapt to this re-optimization?

II. Material Convergence = Demands for Recognition

Historically, when countries or social groups have experienced the type of convergence we’ve observed over the last three decades—increased wealth, increased education, more inclusive politics, and greater connection via new technologies—we’ve seen these newly empowered groups then demand, organize, and agitate for more privileges and recognition.

When these demands occur, sometimes incumbent elites make concessions to these newly empowered groups in a relatively bloodless way—think Britain’s Glorious Revolution that affirmed the primacy of Parliament over the King in 1688. And at other times elites refuse to compromise and full-scale rebellion, revolt, or revolution ensue with a lot of bloodshed—think the American and French revolutions following the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution. At the end of either scenario, a new political equilibrium is typically reached. First the burning down of the old, then the weird emergence of the new.

Similar trends are playing out today. Today and over the next few decades these same four mega-trends, alongside a fifth—the removal of American hegemony—will co-mingle and conspire to impel newly empowered groups to increasingly push for new political accommodations, for new institutional arrangements that formalize these accommodations, for different ‘rules of the game’ that satisfy the newfound desires of ascendent groups for recognition.

Today, Russia and Ukraine are engaged in one such war for recognition, each side vying for new political accommodations. Russia: for recognition that, in Putin’s words, Russians and Ukrainians “are one and the same people.” Ukraine: for recognition that its people comprise a unified and cohesive national identity—distinct from their Russian cousins—in their dedication (however nascent) to more European values of pluralism, liberalism, and self-determination.

These same battles of recognition are set to play out across the world, especially in nation states that were birthed not as the result of natural political evolution (i.e., the Tillyian ‘states-make-war-and-war-makes-states’ flavor of European state formation), but instead came into being as the result of artificial border drawing. African countries are especially affected by artificial borders.

Within the borders of these more artificial nation states are contained the seeds of several latent, as yet unrecognized or unempowered identities and social groups, lying somewhat dormant just waiting for a spark to ignite them. The confluence of the above five mega-trends is that spark. The question then becomes—to continue with the language of Mark’s #burning20s tweet—what kind of fire will the spark yield: a violent inferno or a controlled burn?

The answer to this question depends on how quickly and effectively institutions are able to adapt, which shouldn’t leave us overly optimistic.

When it comes to questions of nation states and potential changes to their borders, prevailing institutional arrangements today lack a viable way to settle these disputes quickly or adequately. Typically, responses fall into one of two camps. The first camp believes international borders ought to remain unchanged, despite their discordance with existing patterns of group settlement. This camp is exemplified by the speech given by Kenya’s ambassador to the UN, Martin Kimani, following Russia’s recognition of two Ukrainian regions (Donetsk and Luhansk) as independent states on February 22nd. Ambassador Kimani said,

“This [Ukrainian] situation echoes our history. Kenya and almost every African country was birthed by the ending of empire. Our borders were not of our own drawing…. Today, across the border of every single African country, live our countrymen with whom we share deep historical, cultural, and linguistic bonds…. Instead [of relitigating artificially drawn borders], we agreed that we would settle for the borders that we inherited…[w]e chose to follow the rules of the Organization of African Unity and the United Nations charter, not because our borders satisfied us, but because we wanted something greater, forged in peace.”

The second camp believes that international borders—at least some of the most artificial and untenable of state borders—should be redesigned. Political scientist Jeffrey Herbst is a good example of this second camp. Herbst wrote,

“Unfortunately, despite spectacular state failures…[f]ew ask if it would be better to try to redesign at least some African states. [Instead], the international community acts like creditors who, having seen their investment lost by a company without a viable business, seek to reinvest in the same company after bankruptcy has been reached but without demanding a restructuring that would protect their investment…. The overarching goal of developing alternatives to African states should be to increase the congruence between the way that power is actually exercised and the design of [new political] units…alternatives must, in the end, come from the Africans themselves.” (p. 258-61)

Both camps ultimately fail. The first because the risk of underlying ethnic tensions within fractionalized states erupting into outright violence is not resolved, and this risk will grow ever-greater due to the ongoing influence of the five mega-trends—a spark waiting to ignite. The second camp also fails because it’s a political non-starter. As Herbst rightly points out, “alternatives must…come from the Africans themselves,” but pan-African institutions like the Organization for African Unity and the African Union—along with their member states—have made it crystal clear that their ongoing policy is to uphold and respect inherited borders, no matter how artificially drawn (there are the occasional exceptions, like South Sudan and Eritrea, relatively new states that emerged after long wars).

So, how to get around this impasse? How to enable institutions to adapt to and give recognition to ascendent social groups, but at the same time avoid fundamentally re-ordering state boundaries given political elites seem united in their aversion to such a re-ordering? Are there any in-between solutions that can help bring about a controlled burn rather than a violent inferno? Charter cities can help play a role.

III. Charter Cities as Controlled Burn

It’s important to note that charter cities—new cities with new rules—would not be needed in a first-best world, or even a second-best world. The first-best solution to the above problems is that a nation’s political class simply responds to its people’s demands for recognition and passes reforms accordingly. But incumbent elites today and historically have proven more interested in entrenching their own privileges (or those of their group) by keeping out new entrants than in opening up the political space to marginalized groups. Therefore, these institutional reforms seldom occur, and if they do occur are typically undermined or stymied during implementation. Mancur Olson calls this situation institutional sclerosis.

A second-best solution would allow the citizens of the sclerotic nation to opt for political exit. That is, if dysfunctional countries fail to reform themselves, high-income, well-functioning countries should permit the in-migration of these citizens. Lant Pritchett, Michael Clemens, and others have been pushing rich countries to open up their borders to workers from low-income countries for just this reason. Comparing the income gains poor migrants can attain from moving to a high-income country with the gains from some of the best, RCT-tested development interventions (e.g., cash transfers, the ‘graduation’ approach, and other health interventions), Pritchett finds the impacts of these ‘best-you-can-do’ development interventions to be “about 40 times smaller than the income gain from allowing people…to work in a high productivity country like the USA.” Not to mention, the mere option of political exit would likely have a disciplining effect on the dysfunctional country, spurring it to at least partially reform in an effort to retain its most talented citizens (and tax base).

But again, the problem with this second-best solution is tractability. With the spread of populism, democratic backsliding, and anti-immigrant sentiment across many high-income countries, political leaders from the West are understandably reluctant to further fan these xenophobic flames by significantly opening up their countries’ borders. Thus, borders remain closed, and increasingly frustrated citizens (750 million of them to be exact) are prevented from migrating, remaining unrecognized and marginalized at home—a spark waiting to ignite.

Charter cities can move the needle. Because charter cities are delimited to a concentrated, city-scale area within a host country and are located on greenfield land, they can largely circumvent Olsonian institutional sclerosis. With the city’s special jurisdiction applying on a chunk of sparsely populated land, there are no (or at least very few) entrenched political interests standing by to undermine any attempted reforms. Because their rents remain unthreatened, these elites will likely remain if not actively supportive then at least indifferent. The charter city can therefore implement much deeper institutional reforms than otherwise possible at the national level.

Additionally, those newly ascendant social groups grasping for a better life will find a jurisdictional enclave that fully recognizes their equal right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, as charter cities are predicated on equal protection before the law and an openness to all. And any resident of a new charter city has made a voluntary choice to move there, fulfilling desires for self-determination.

At the same time, because charter cities are not sovereign and remain part of the host country, they do not violate the ongoing policy of international institutions like the AU, the UN, and the Organization of African Unity to “settle for the borders that we inherited,” as Ambassador Kimani put it.

Ultimately, for hundreds of millions around the globe whose incomes, education, and access to communication technologies have seen convergence with rich nations over the last 30 years, now that basic needs have increasingly been met, they seek more. They seek not just the subsistence known to innumerable ancestors, but human flourishing unimaginable to even their parents. For many of these masses this is a time of unprecedented firsts. It’s the first time not only that a consciousness of a broader social contract has taken up a sizable proportion of their attention (previously preoccupied mainly with survival), but it’s also for many the first time (i) they’re actually able to read that social contract, (ii) to organize and mobilize their social groups with cheap technologies to bargain for a better contract, and (iii) to witness—via the internet and smartphones—how the social contracts of other countries around the world compare to theirs at home. Many find their social contracts wanting, and will demand more.

While charter cities are not a first-best solution, we don’t live in a first-best world. Charter cities are able to thread the needle—giving much-desired recognition to newly empowered social groups, while respecting sovereign international borders that political elites are intent on maintaining. Though weird, charter cities allow for a controlled burn, and avoid a violent inferno.