In 1859 Charles Dickens opened The Tale of Two Cities with one of the most memorable lines in literature,

‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of credulity…’’

Though written about the French Revolution (1789) these opening words could equally well have described a revolution that overlapped with the literary life of Dickens. This was the U.S. railway mania in the 1850s and 1860s. It was a ‘mania’ relative to the number of track miles rapidly constructed, the unprecedented financing, the number of new companies opened and the public fascination stoked by lurid newspaper headlines. In the US during the 1850s 22,000 miles of track were laid and the entire eastern seaboard was linked. The most dramatic mania was the 1860s race between the Union Pacific and Central Pacific companies to cross the continent and build the Transcontinental Railway.

In 2022 there is a new railway mania, this time in Africa. Will this contemporary mania be marked more by ‘wisdom’ and ‘belief’ or by ‘foolishness’ and ‘credulity’?

I know a good plot should leave the denouement to an exciting climax, but forgive me dear reader if I let you in on the secret now.

The answer is both.

The African Railway Mania will be the best of times and the worst of times.

Let me explain why…

First we need to return to our historical examples.

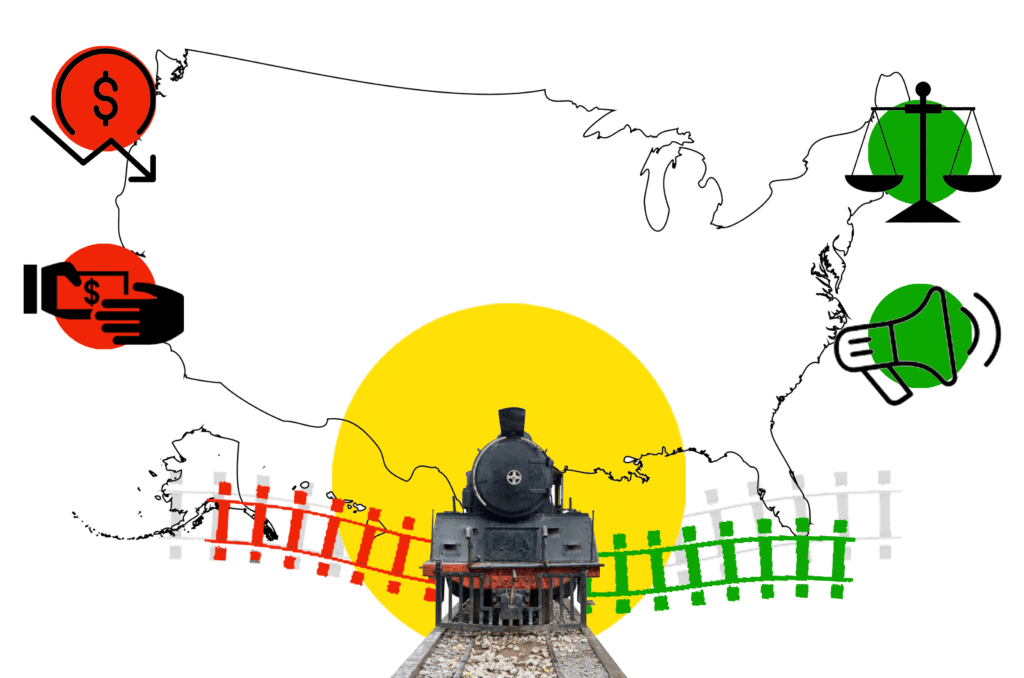

It was the best of times. The US railway mania drove organizational innovation. The railway system bestriding the prairies of a poor developing country required an unprecedented volume of finance. By 1873 US railways were synonymous with the stock market. The finance-voracious railway companies held 80% of total stock market capitalization. Other railway-inspired financial developments included investment banking, security brokerage, and legal firms specializing in corporate law.

It was the worst of times. Even as they were created these new organizations were riven with corruption and malpractice. In the US the directors of the Union Pacific transcontinental railway plucked an unknown firm hitherto dozing in rural obscurity. The Pennsylvania Fiscal Agency was renamed with a touch of Parisian louche and became the Credit Mobilier (CM). CM was turned into a construction company, coincidentally entirely owned by the directors of the Union Pacific. Despite charging outrageous sums for construction work CM continued to win contracts from Union Pacific. By late 1869 Union Pacific had failed to pay its workers for eight months and was teetering on the verge of bankruptcy, to the consternation of its army of stockholders. Union Pacific CM was doing rather well and paid a huge dividend to its coterie of far-sighted owners.

It was the best of times. Railways changed the way the population of the US thought about the world, they lifted up eyesight and political opinion from the limited horizons of horse-and-cart economies. The railways facilitated the growth of a national news media through the physical delivery of newspapers. The railways tried to control the press through paid advertising, free travel passes for reporters, and commissioned articles. Ultimately the truth came out and the media exposed corporate railway misdemeanors. In September 1872 the New York Sun broke the story of Credit Mobilier bribing their way into the hallowed portals of Congress. In 1886 the journalist James Hudson published ‘Railways and the Republic’. The book was an influential expose of how the railways had been funded by overly generous land grants and then used discriminatory pricing to squeeze more profits out of farmers. In the wake of this journalism was the national anti-monopoly crusade of the 1880s. The railway behemoths were tamed through popular politics and federal legislation.

And back to contemporary Africa…

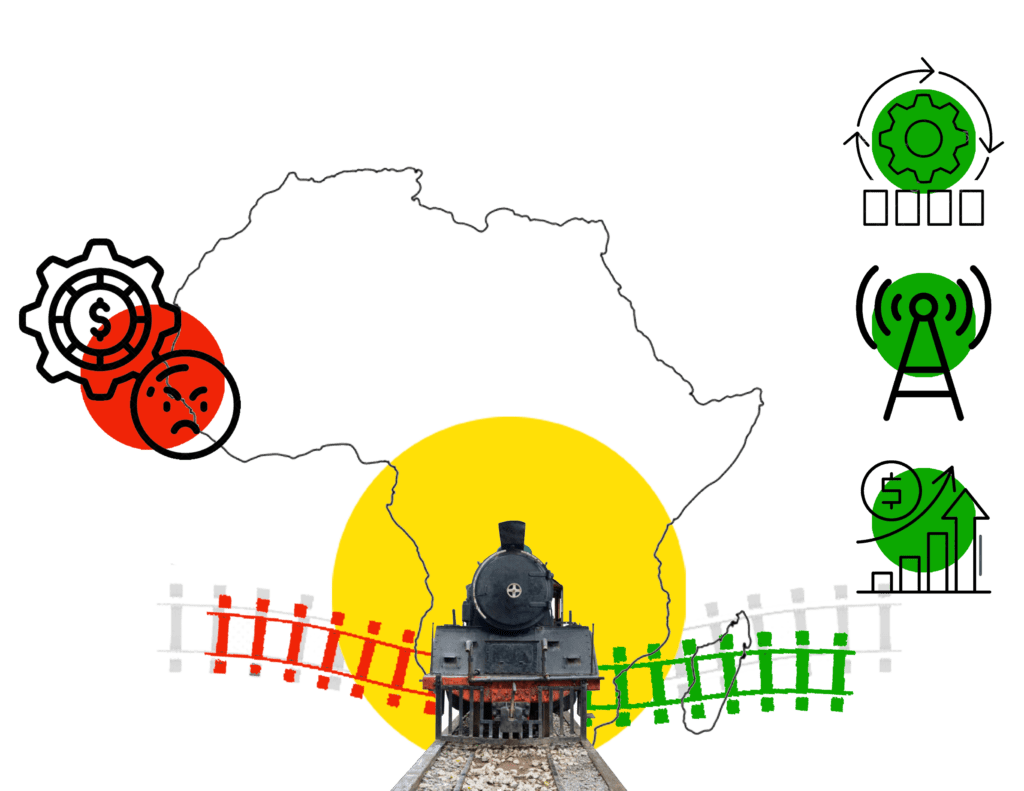

In 2022 a new mania has erupted into global development discourse and popular media. Global finance is thrilled and the eponymous dollar-filled suitcases have started arriving in African capitals. The African Development Bank (AfDB), the World Bank (WB), the US government, and especially the Chinese inspired Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have all lauded African railways and promised financial backing. The trains have started running. In 2017 the $3.8 billion 480km line from Nairobi to Mombasa (Kenya) and $4.5 billion line from Addis Ababa (Ethiopia) to Djibouti were both inaugurated. In September 2021 Egypt signed an $8.7 billion deal with the German company Siemens to build a 1,800 km electric railway between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean where trains would link 60 cities and reach a top speed of 250 km per hour. High speed trains are already whishing through Morocco, Nigeria, and Tunisia.

We are headed for the best of times and the worst of times.

It will be the worst of times. When resources flood into a country, whether revenue from oil sales, or surges in foreign aid or, in this case, railway financing, then governance suffers. The empirical evidence demonstrates a clear link between higher foreign resource flows and declines in the quality of governance. Much of the African railway financing comes from China. It is a proud point of Chinese principle to offer loans without any conditionalities. Chinese investment in Africa is not going to countries conditional on them making efforts to improve governance or to reduce corruption. Mozambique and Zimbabwe experienced sharply declining measures of governance between 2012 and 2016 yet China continued investing.

It will be the best of times. Chinese-funded infrastructure in energy, telecommunications and transport is addressing critical constraints to African economic growth. Better infrastructure will boost economic growth across Africa. As people become richer they demand better governance, better public services, more security, law and order and greater political participation. This dynamic was captured by the 1959 Lipset Hypothesis that showed how democratization follows income growth. Chinese manufacturing firms have responded to better infrastructure by investing across Africa. A McKinsey survey in 2016 estimated that Chinese manufacturing firms in Africa were producing $60 billion of output. African manufacturing is learning from, sub-contracting for and expanding in the wake of Chinese manufacturing. Successful manufacturing firms will demand legally enforced property rights to better protect their investments. Governments will oblige as manufactured exports generate politically important employment and wealth. Recent history gives us many examples. The voluminous list includes China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, Tunisia, the Dominican Republic and others. All these countries had governance as weak as those in 2022 Africa when they began their manufacturing export induced ascent to prosperity and better governance.

To give one African example.

It was the worst of times. The Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) connects the Kenyan capital Nairobi to a port in Mombasa. The construction prompted a frenzy of bad governance directed from the office of the Kenyan President – a Presidential election was looming. Government regulations regarding procurement (contracts for political connections) and the financing arrangements (an election had to be paid for) were ignored.

Will it be the best of times? Echoing the vintage US media, in Kenya, Chinese investment was subject to scrutiny by a free and independent media. Concerned about its global image the Chinese government responded and sought to ensure compliance with local environmental and social regulations. The Chinese construction firm engaged in the building work released a Corporate Social Responsibility report in 2016, a first for a Chinese firm operating abroad.

Since the inauguration of the SGR in 2017 the Kenyan economy has surged. GDP growth increased from an anemic 3.8% in 2017 to 7.5% in 2021. Growth of industrial value added increased from 2.76% to 7.17% over the same years.

History says we should be optimistic about Africa and Kenya. Railways drive economic growth. Economic growth drives institutional change.

We can turn to the immortal lines of another Dickens favorite, Oliver Twist (1837), to describe Africa’s optimal long-run railway strategy.

“I want some more!”