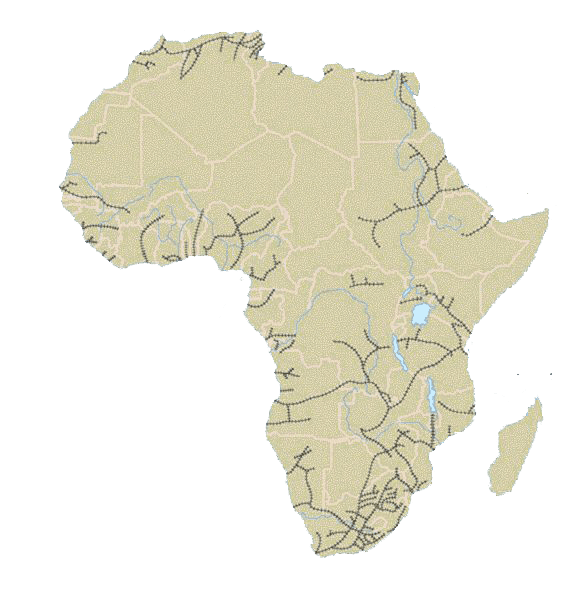

Look at a map of train lines on the African continent in the early decades of the twentieth century.

It looks peculiar doesn’t it?

It looks as though someone has taken a knife and slashed lines from the coast. A bit like a Cornish Pasty if you are familiar with that icon of gourmet English cooking.

That was colonial railways – lots of short lines that connected interior areas rich in natural resources to coastal ports. This was a railway system based on extraction and one that led to national dis-integration. National disintegration by a thousand cuts. Railways were typical of colonial infrastructure. A telephone call from Accra (Ghana) to Abidjan (Cote D’Ivoire) had to go via an operator in London then via Paris. Colonialism was about binding colonies to the colonizer, not about creating regional or international economic links. Coercive colonialism was structured around extracting raw materials and profits and maintaining political control, railways did both.

Ghana was typical. In the late nineteenth century Britain built two railway lines to link the coast to mining areas. These lines went through “dense, low-populated tropical forests”. Eventually those forests were cleared and planted with cocoa – Ghana became the world’s largest exporter of cocoa.

We can follow that cocoa across its international voyage into the depths of a succulent Sacher-torte cake served at Café Frauenhuber in Vienna. Taking spoons of that choclate-y indulgence were the nineteenth century residents of imperial Vienna. Across the Austro-Hungarian Empire all railway lines led to Vienna and converged on the Sacher-torte. Railways were structured around linking up the great cities of the empire, Vienna, Linz, Krakow, Budapest, and Prague. The Austro-Hungarian railways were about centralized control and nation-building or national integration. Railway lines look more like a spider’s web than a Cornish pasty!

It is now 2022.

After decades of civil war peace returned to Angola in 2002; even by 2009 80% of Angola’s infrastructure was not operational. In March 2005 China’s state owned Exim Bank pledged more than $10 billion in credits to be directed towards infrastructure development and rehabilitation. The projects were to be paid for by shipments of Angolan crude oil to China. In 2008 Congo agreed to a $9 billion loan from China (later reduced to $6 billion after disgruntled muttering from the World Bank) to rebuild thousands of miles of roads and railways. In return Congo gave China the rights to five copper and cobalt mines in the South of the country.

The ever imaginative and creative fraternity of global economists gave this exchange the snappy and witty label, ‘infrastructure-for-resources’. Note the clever use of hyphens.

Is history repeating itself?

There is an external great power waving a checkbook – tick.

There is a scramble for natural resources to fuel the consumption and manufacturing import needs of a great power – tick

There is a railway building boom – tick

Is this colonialism mark 2?

Is Africa riding a new journey into colonialism aboard Chinese trains?

Well. Not really. Let us ponder one of the many (but very similar) definitions of colonialism. This perfidious practice can be defined as:

“the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.”

Lending money is finance. Buying natural resources is about trade. Building railways is about infrastructure. No political control or settlement, so no colonialism surely?

It isn’t colonialism yet. But railways don’t stand still – apart from British trains that have acquired a stationary predilection of late owing to a wave of strike activity. Chinese trains certainly don’t stand still. Railways are about journeys and the final destination is crucial.

Acquiring control over the major natural resource and source of foreign exchange could give China enormous political influence. It is Chinese state-owned banks and state-owned construction companies that are lending the money and building the railways. Meaning, that potential influence is mediated directly through the Chinese state. The thousands of Chinese workers, managers and traders accompanying railway construction could give China the agents to exercise political influence. Control over the basic infrastructure, the ports and railways could give China leverage over the commanding heights of the economy.

Remember the Suez Canal? It was built by a private French company and opened in 1869. The canal, connecting Europe to colonial empires in Asia soon became the subject of a great power tussle between France and Britain. The money Egypt borrowed to finance the canal tipped the country into a debt crisis. Egyptian sovereignty was quietly devoured by English finance. By 1882 Egypt was a colony of the UK. There is a very similar and influential contemporary narrative about China; that is debt-trap diplomacy – China lends money and gains control of natural resources and infrastructure, the money can’t be re-paid and China doubles down on political influence. Just for the record, I don’t personally believe China is engaged in systematic debt-trap diplomacy, but it is a powerful and emotive idea.

A railway journey to new colonialism? Not if the African Union (AU) can help it. The AU has a big, bold and alternative vision for railways.

The African Union (AU) vision for 2063 ‘The Africa We Want’ envisages a “Pan-African High Speed Train Network will connect all the major cities of the continent.” The High Speed Railway project was endorsed by the AU Heads of State at a summit in 2013. The planned single-gauge network promises to connect the 16 landlocked countries in Africa to major seaports and neighboring countries.

The AU as an all-Africa organization is needed for three reasons.

First, continental railways are subject to significant coordination failures. There are currently four gauges used in African railway tracks which means national railway systems are not compatible with each other. The AU has mandated one Africa-wide standard gauge.

Second, there’s a big market failure in the construction of intra-national transport links such as railways. For a landlocked country in Africa there are crucial external benefits if others build railway lines. Improving the railway line in Uganda for example would have little effect unless there were similar improvements in the line as it passes through Kenya on the way to the port in Mombasa. Why should Kenya take into consideration those external benefits to its investment for Uganda? The AU has started with a continent wide vision that accounts for these externalities.

Thirdly, continental trains are useless if trade and people are stopped at every national border. Sub-Saharan Africa has strikingly low levels of intra-regional trade in part because of long-delays and bureaucracy at borders. In 2018 44 countries signed the AU inspired African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) committing themselves to end cross-border tariffs and 27 countries signed a protocol for the free(er) movement of people.

If the AU dominates the railway agenda then construction is more likely to emphasize connecting up urban areas across borders. An intercontinental railway-infrastructure network can help make a break with dependence on raw material exports and promote intra-African trade, industrialization and urbanization. The AU has worked hard to promote its own diplomatic engagement with China. The AU participated in the 2012 Forum on Africa-China Cooperation (FOCAC) in Beijing as a full member. China then established a permanent mission to the AU in 2015. AU agency is evident in the agenda for discussion at FOCAC events which are not just set by China. The AU Agenda 2063 was incorporated into a 2015 FOCAC Action Plan. The AU still needs to be more empowered by African states to negotiate on their collective behalf. This requires a mini-revolution, for African presidents to give up some of their power to the AU in exchange for more collective sovereignty.

That’s difficult.

Africa needs a new vision for this age of coal, copper, and cobalt laden Chinese railways, to pool sovereignty at the national level to better retain African sovereignty at the continental level.