This Earth Day, it’s time to admit that one of the most promising solutions to climate change is too often excluded from the conversation: cities. Instead, cities are often portrayed as the cause of climate change. According to the United Nations, cities are responsible for over 70% of greenhouse gas emissions despite only occupying 2% of the world’s land. Others have highlighted the congested and polluted forms that many cities take, especially in the Global South.

We are more optimistic. Cities are one of the most effective tools to fight climate change. By concentrating human activity into small areas, cities limit the burden civilization places on the natural environment. Cities also reduce transportation emissions and improve energy efficiency compared to sparse suburbs and rural communities. These benefits are a consequence of urban density, which helps cities achieve greater economies of scale and distributes resources more efficiently across a larger population.

To investigate this theory, we analyzed a relatively new dataset of 343 global cities. Cathy Nangini and her coauthors (2019) integrated CO2 emissions data from the CDP, the Bonn Center for Local Climate Action and Reporting, and Peking University to create a dataset of city-level greenhouse gas emissions across the world. They also pulled in supplementary demographic and economic data for each city. Unlike many existing city-level carbon emissions datasets, Nangini et al. (2019)’s data is more inclusive of Global South cities.

It is worth noting that the cities included are not a representative sample. As such, many countries and regions may be underrepresented in the analysis. US, European, and Chinese cities make up the largest share of the data. Nangini et al. (2019)’s dataset includes 343 cities, with 174 coming from the Global South (mainly China). We further filtered the data by removing rows with missing relevant variables and a population of less than 100,000 people. The final dataset has 272 cities, with 162 in the Global South.

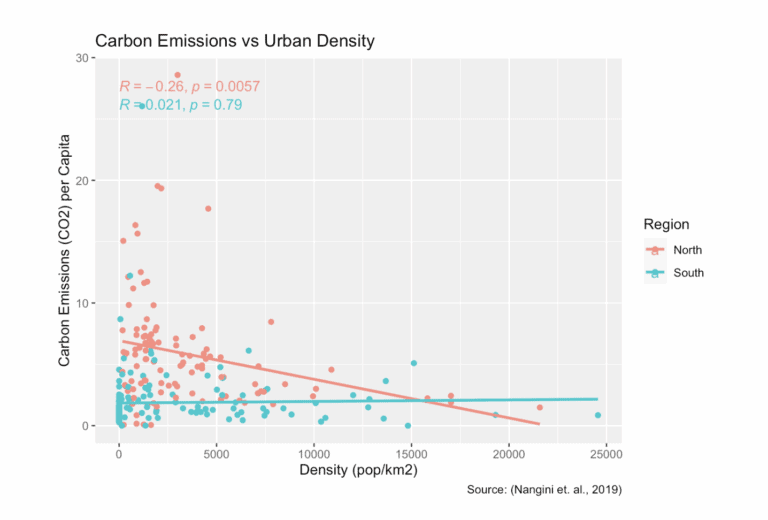

Our analysis looked at how urban density (people per square kilometer) correlates with Scope-1 carbon emissions (CO2) per capita. Scope-1 carbon emissions reflect all emissions produced within a city’s territory. The idea is that while cities may have a larger aggregate impact on the environment, their per capita impact is much lower than other types of communities.

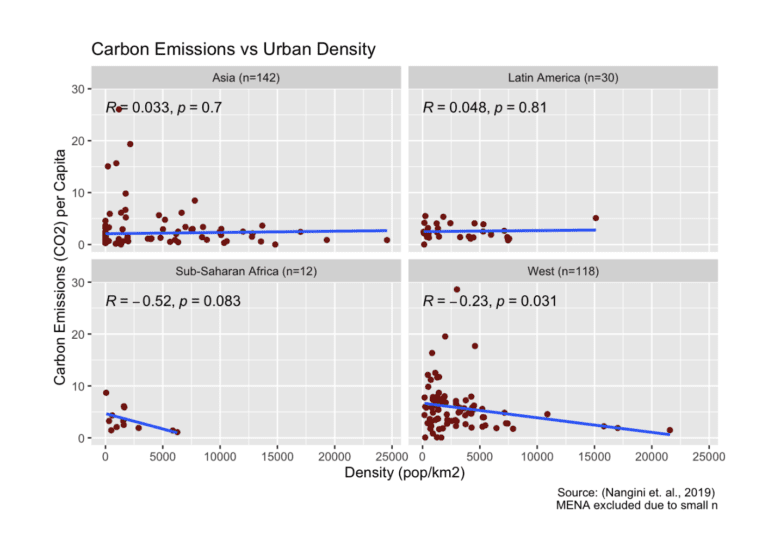

We found no statistically significant (p<0.05) correlation between carbon emissions and density on the global level. However, more dense Global North cities were associated with significantly lower carbon emissions. This was not true for Global South cities as a whole. When broken up further into specific regions, only Western cities continued to show a negative association between density and carbon emissions. Surprisingly, Asia, a region known for its dense cities, did not have the same relationship.

One explanation is that only Western cities are built in a way that takes advantage of the environmental benefits generated by density. This is particularly true of European cities, many of which were designed to be walkable and transit-oriented. The West also has stronger environmental protections and regulations than other regions.

In contrast, cities in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa are more fragmented and reliant on carbon-intensive technologies. This is especially true of African cities, which are less connected, more polluted, and more costly than other comparable cities in the developing world. Urban residents are also forced to live in slums, which have poor waste management and energy infrastructure. In these cases, urban density may increase per capita carbon emissions.

The lesson here is that while density can be a route to reducing our climate footprint, as it is in the West, urban form still matters. That is, density needs to be coupled with other policies to effectively reduce our per capita carbon impact. For instance, it should be easy for urban residents to travel within their cities via public transit and walking. Cities should have access to efficient waste management services, clean stoves, and green energy. Western cities are achieving this, and Global South cities are not.

The geographical gap in climate-mitigating urban development is worrying. In the next three decades, the world will add 2.5 billion people to its cities, and 90% of this growth will take place in Asia and Africa. If these regions carry on as usual, their cities will continue harming the environment. However, if this period of rapid urbanization is adequately planned for, and if we are able to turn developing cities into dense, well-connected centers (as opposed to hubs of sprawling, car-dependent fragmentation), then urbanization is the best solution to our climate problems. The urban policies we adopt today can help bring about a more climate-friendly future, or not. It’s up to us.

You can find our code on our Github.